Home » Posts tagged 'Church Reform'

Tag Archives: Church Reform

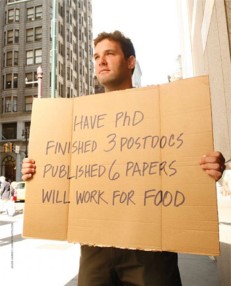

If I wanted to be wealthy, I should have been a priest

What is missing in the 2017 National Diocesan Survey on Salaries and Benefits for Priests and Lay Personnel? (Commissioned by the National Association for Church Personnel Administrators [NACPA] and the National Federation of Priests’ Councils [NFPC], it was carried out by the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate [CARA]). The overview seems both modest and comparable to the typical lay ecclesial minister’s income:

If I were a priest, I could probably afford the $795 that NACPA is charging to download a copy of their full study, and find out in closer detail. But as a lifetime lay employee of the Church, I have to take it as a given that the good people at NACPA (mostly lay pastoral administrators) have crunched their numbers accurately and the $45,593 is in fact the median taxable income of U.S. priests. A table of contents is publicly available which indicates what they did (and did not) consider.

What about the untaxable income? What about the things that are hard to quantify but observably make a difference? Or easy to quantify but simply taken for granted? What about the expenses that the lay counterpart has that the priest does not? A penny saved is a penny earned, after all.

A pastor I know complained – often and loudly – that he was paying the lay pastoral staff at his new assignment far too much (A little less than $50,000 per year, less than the state’s average income[1]). To his credit, the pastoral council president, who had been involved in the hiring process with the previous pastor, usually replied that the staff were paid about 1/3 of what they were worth in the private sector, and the young priest should be a little more appreciative.

Fr. Scrooge’s attitude got me thinking about the apparent disparity between compensation for equally qualified people with a vocation to ecclesial ministry.

Look at two people of reasonably comparable demographic – single, no children, with undergraduate and graduate degrees in theology/divinity, committed to a life of ministry in the Church – and consider them in a similar parish, similar ministry, with similar qualifications, experience, and responsibility. One is a priest, the other a lay ecclesial minister.

There is no question the priest in such a scenario is “wealthier” – enjoying a higher standard of living, a nicer house, with greater stability, and less stress about making ends meet. So how does this observable reality reconcile with the apparently low income that priests have, according to the NACPA study? Something is missing.

Considering a few major areas of disparity, we can easily track how those pennies add up, taxable or otherwise.

Education

Source: Mundelein Seminary

In the U.S., the standard education and formation program for a priest is to have a four-year Bachelor’s degree (in anything, really, but with a year’s worth of philosophy and theology at the undergrad level before graduate seminary), and a three-year Master of Divinity or equivalent, plus a pastoral internship year. Most lay ecclesial ministers have something similar, if, of necessity, in a greater variety of configurations.

In one diocese I am familiar with, the entire cost of seminary is covered, at least from pre-theology onward, plus a variable stipend for travel and spending. For college seminarians, the students are accountable for half their cost (which could be covered by scholarships they earned from the university, for example).

The average cost of tuition and fees at Catholic colleges and universities in the U.S. in 2016-2017 was about $31,500, with the highest ones being around $52,000 (Source: ACCU). So let us say the diocese i mentioned is typical, and pays for two years of the undergraduate and all three years of the graduate costs for formation: middle-of the road estimate of $157,500 per seminarian.

An additional spending stipend can range from $2000-$6500 per year depending on where they are in studies. Let us say $4000 a year for ease of calculation. An additional $20,000 brings the educational investment up to $177,500. It would be interesting to see what the actual numbers on this spending are.

The candidate for lay ministry, on the other hand, has to work or take out loans, though in some places some assistance is available. Forty years ago, one could work full time at a minimum wage job in the summer to pay for a year of tuition at a respectable state school, but that has not been true since the 1980s. Despite savings, work-study, scholarships and grants, and, if fortunate, parent contributions, the average graduate leaves with $38,000 in student loan debt after a Bachelors, and about $58,000 all told if they have also a Masters from a private institution, which has to be the case if you have a degree in theology. (Source: Newamerica.org study, Ticas.org). The interest on that, at the standard federal rate of 6% over the life of the loan (twenty years) will add another $19,000 to the total.

So far, in terms of pennies saved and earned, the priest is $196,500 ahead, and ministry has not even begun.

But we are not done: the best and brightest are often called to graduate studies, say, a license in canon law or a doctorate in theology.

Another three years of graduate school for a JCL (or five, at minimum, for a doctorate). In Rome, where tuition is cheap but living is costly and jobs are hard to find, it is easy to contrast the stability and support given to clergy with the complete chaos experienced by most laity – who, nevertheless, sacrifice more and more in answer to a vocation to serve the Church.

About $25,000 a year, (choosing the cheaper options of a canon law degree in Rome), and there’s another $75,000 where our priest has uncounted ‘income’.

He is now $271,500 better-off than the lay counterpart …and we are not even counting the little extras Knights of Columbus ‘pennies for heaven’ drives or Serra club gifts.

Note, too, that the priest-grad student continues to draw a salary/stipend, plus other benefits like housing and food stipends, while in studies; the lay minister has to give all this up to pursue studies. According to the study, that means adding another $45,000 per year to the priest’s advantage.

So, make that $406,500 ahead of the lay minister with the same education.

Housing

St. George Parish Rectory, Worcester, MA.

Housing was calculated in the NACPA study, either (or both?) in terms of taxable cash allowances and housing provided, but it is hard to reconcile the low-ball numbers given with the observable reality: Priests living alone in houses that are considerably larger and/or nicer than what their lay counterpart could ever afford to live in. How is this possible?

Simply ask the question: What is the value of the house (rectory) and what would it take to live there?

You can either look at the value of the rectory and estimate the salary required to afford such a place; or you can look at the salary earned and look at how much house someone with that income can afford, and how it compares.

Based on the 2012 CARA survey (being unable to see the 2017 median salary as it is behind a paywall), the median annual salary in 2010 was $34,200. That’s about $38,351 in 2017, factoring for inflation. Assuming no other debts (ha!), that means one could afford a house valued at about $185,000, considerably less than the median price.

The median house value is about $300,000 in the U.S., based on sales prices over the last year (Source: National Association of Realtors). To afford this, one would have to be making about $65,000 a year, at least, and paying $1800 a month mortgage or rent.

But is the typical rectory more or less expensive?

As a point of reference from which to extrapolate, I checked on the value of the rectories in the five parishes where I have lived and worked in the last twenty years. (Source: Zillow). I then compared their value to the median house value in the same cities or regions.

- Everett, WA Rectory Value: $550,000. (Median House: $330,000)

Estimated monthly payment: $3560. Recommended income: $120,000 per year. - Woodinville, WA Rectory Value: $641,000. (Median House $755,000)

Estimated monthly payment: $4366. Recommended income: $146,000 per year. - Bellingham, WA Rectory Value: $700,000. (me Median House: $415,000)

Estimated monthly payment: $4480. Recommended income: $150,000 per year. - Bothell, WA Rectory Value: $951,000. (Median House: $529,000)

Estimated monthly payment: $6051. Recommended income: $202,000 per year. - Edmonds, WA Rectory Value[2]: $1,600,000. (Median House: $541,000)

Estimated monthly payment: $10,281. Recommended income: $343,000 per year.

The average rectory value was $888,400 in a region where the average house is valued at $514,000 (or, 172% the price of a ‘median’ house). Only in one case was the rectory valued lower than the typical house, and in most cases they were considerably higher. One would have to be earning an annual salary at least $192,200 in an area where the median household income is $58,000, in order to live in these rectories – and most Church employees are not even making the state median income.

Extrapolating this trend to the national median house price, we could estimate that the national typical rectory is valued at about half a million dollars, meaning a mortgage or rent of $3000 a month for the lay employee wanting to buy or rent the same place. An additional $36,000 a year is well beyond the taxable extras indicated by the NACPA survey. The main reason for this is probably that many of the properties are already owned in full by parish or diocese, so the cash flow is calculated differently, but to my question: what would it take for the lay employee to live there, this is the more accurate measure of wealth differential.

Our priest is now not only $406,500 better off to begin with, but at an advantage of $36,000 per annum. On average. In a place like western Washington State (where my rectory examples are from), the annual disparity is nearly double.

Unemployment

These days, it is not unusual to be without work for some period of time, no matter how educated, skilled, or driven one is. Though Baby Boomers tend to think of these as irregular, it is an expected part of professional life for GenX and Millennials. About 1 in 5 workers are laid off every five years, in the twenty-first century, and 40% of workers under 40 have been unemployed for some significant amount of time in their short careers. I can only imagine this statistic is higher for those who have worked (or tried to work) for the Church.

When a priest is incompetent, or just not a good fit for a particular job or office, it is almost impossible to have him moved or fired. Even when he does, his livelihood is never in question.

Even when a lay minister is at the top of his or her game, an economic downturn will affect them far before the priest. Our exemplar lay minister not only has to worry that he could lose his job just because the new pastor does not like lay people or feels threatened by anyone with a theology degree besides himself, s/he has to worry about more than just a loss of respect or office, but something as simple as whether or not he can afford a place to live, health care, or the cost of moving to a new job. Lay ministers are not even entitled to state unemployment benefits, being employees of a religious institution. If he or she is out of work for a month or two, that means a significant loss of income and increase in stress, not vacation time.

How do we quantify this? Certainly, the psychological advantage of knowing you have virtually untouchable job security is priceless. Based on some (admittedly unscientific) survey of other lay ecclesial ministers, an average seems to be about one month of (unpaid, involuntary) unemployment for every three years of working for the Church. Based on the median annual pay and benefits of such ministers, that’s a little more than $4300 in lost income and benefits every three years, or about $1450 a year we can add to the priest’s income advantage, which now stands at $406,500 out of the blocks and $37,450 annually.

Blurred boundaries and clerical culture

Some years ago, I was at a conference once with several priests, and we decided to go out for a steak dinner at a nice downtown establishment. One of the priests (soon after, a bishop) reached for the bill, pulled out a credit card, and said, “Dinner’s on the parishioners of St. X’s tonight!”

Whether he meant the he was paying out of his own pocket for our dinner but realized his salary came from parish giving, or that he was using the parish credit card (and budget) was a little unclear, but it seemed like the latter.

Even the most well-intentioned priest is hard-pressed to clarify where his personal finances begin and the parish’s ends in every case, especially as he has essentially full control over the latter, what with most parish finance councils being merely ‘consultative’. For those who feel they are entitled to the benefices of their little fiefdom, it is only too easy to meet basic needs without even touching one’s official salary or stipend.

Sometimes it is a result simply of not knowing any other way. When I was a grad student, the then-chair of theology was a Benedictine monk. At the end of my first year, he called me in to inquire why I, as a scholarship student, was not getting straight A’s. When I mentioned the 25-30 hours I put in at work each week, he was perplexed: why was I working while in studies? I pointed out that my scholarship covered only tuition, and not university fees, housing, food, insurance, travel and transportation, books, computer, etc., he sat back and with a rather distracted look on his face said, “Oh… I forgot about all that.” Such is the advantage of the ‘wealthy’ – even in vows of poverty!

I cannot calculate the untaxed income of intentional or innocent blurring of boundaries between budgets, but we would be naïve if we did not realize that our current quasi-monastic compensation structure lends itself to confusion at best, and abuse at worst. Certainly, most priests are among the well-intentioned and conscientious in this regard. That does not mean we cannot improve.

Conclusions and Solutions

Fifteen years after ordination or the beginning of a career in ministry, our two Church ministers are sitting quite differently. Nearly $970,000 differently, in fact. Our priest started with $406,500 in education advantages, and enjoyed housing and security advantages at a rate of $37,450 per year.

In other words, in order for our lay ecclesial ministers to be living on par with our priest – their average salary should be about $96,000 per year (plus benefits) – nearly triple the current reality. (Calculated by dividing the education advantage over twenty years, and adding the annual advantage to the average annual pay).

Remember, this is not all cash in hand, or the kind of wealth you can take with you (I know most priests do not own the rectories in which they get to live, but then, most lay ministers are renting too.). Nor is this all of the same quality information – some is based on extensive national study, but where data is lacking, we have had to estimate a median goal by extrapolating from known reference points. Obviously, that means i will continue to update the figures up or down as more or better information presents itself.

But in terms of, “what would the lay minister’s salary have to be to enjoy the same ‘wealth’ as a priest” there is your answer. These are expenses the priest never personally had, that the lay minister did or would have to have had to live in the same houses, have the same education, etc.

So how can we make our compensation structure more just, more transparent, and more equitable?

The detailed information in the NACPA study helps, but it only address some of the problems. Accounted taxable income is only a portion of the income disparity, as we have seen. So what could we do differently?

Perhaps when a bishop or pastor hires a lay ecclesial minister, he should compensate them for the education they paid for that he now gets to take advantage of, to the same degree as what he would have paid for a priest in their situation? How does a $406,500 signing bonus sound? At the very least, compensate the individual as you would a fellow bishop when a priest from his diocese is excardinated from there to join yours.

On that note, all ministers should be incardinated, or registered, or something. It really makes no sense, ecclesiologically, to have any kind of ‘free-agent’ ministers in the Church, which is how our lay ministers are treated. All ministry is moderated by the bishop, and all ministers are, first of all, diocesan personnel, ‘extending the ministry of the bishop’. They should be organized, supported, and paid as such. (At the bare minimum, they should show up in every dioceses’ statistics on pastoral personnel!)

I am a big supporter of the idea that all of our ministry personnel – presbyters, deacons, and lay ecclesial ministers – should all follow the same compensation system and structure. Preferably, a straight salary. This clarifies the boundaries, makes real tracking of compensation easier, and clarifies comparable competencies.

Wherever the Church wants to remain in the real estate and housing business – though i am unsure if it should – these should be administered at the deanery level and set up as intentional Christian communities for ministers. Will have to write something else about this.

The same should be said for support and funding for formation and education. When the majority of parish ministers are lay ecclesial ministers (which has been the case for over a decade in the States), the majority of funding should be going to support their formation.

The same is true for advanced studies. Too often bishops seem to forget that their pool of human resources is wider than just the presbyterate. Raise up talent wherever it is found, and you will find dedicated ministers and coworkers for the Lord’s vineyard.

Years ago, I met a young woman who wanted to spend her life in service of the Church, and so was pursuing a degree in canon law. She had written dozens of bishops asking for some kind of support or sponsorship in exchange for a post-graduation commitment to work, and received only negative responses. Her classmates were all priests ten to twenty years her senior, most of whom had not chosen to study canon law, and all receiving salaries in addition to a full ride scholarship from the diocese.

When she and I caught up ten years later, half her class was no longer even in priestly ministry, and she was still plugging along, serving as best she could. Talk about potential return-on-investment! Hundreds of thousands wasted on priests who did not want to study canon law in the first place, a fraction of which would have yielded far better results with this one young lay woman. Imagine how many more are out there denied the opportunity to serve simply because not enough support is offered.

You never know what it is that will catch people’s attention. I hoped this post would provoke some thought, at least among friends and colleagues who read my now very occasional postings, but never thought this would be one to run viral. Read 4000 times here, shared 900 times on Facebook (!), quoted in America and prompting at least one blog in response, i have read and engaged many comments and am adding a follow up to those – many insightful – in a new post.

[1] Household median income is the standard measure of “average salary” in the U.S. census and demographic studies; it includes single-earner households such as our examples of a priest or a single lay ecclesial minister. The average per capita income for the same state was $30,000. (For the county in question, median household income is $68,000 and average per capita is $38,000.)

[2] This is the only one I had to make an estimate. Neighboring houses ranged from $800K to $1.5m, all of which were substantially smaller, on less property, and none of which featured an outdoor swimming pool… So I am, if anything, probably a bit conservative on the estimate.

Papa Francesco: Two Years On

Today marks the second anniversary of the election of Pope Francis as bishop of Rome. They have been, without question, the two most hope-filled years in a lifetime of study and service of the Church. Most people, including most Catholics, have rejoiced in Pope Francis’ style, simplicity, and dedication to reforming the Roman Curia.

Today marks the second anniversary of the election of Pope Francis as bishop of Rome. They have been, without question, the two most hope-filled years in a lifetime of study and service of the Church. Most people, including most Catholics, have rejoiced in Pope Francis’ style, simplicity, and dedication to reforming the Roman Curia.

It made for a great 35th birthday present, very slightly anticipated!

Sadly, this is not a consensus feeling among the faithful, perhaps particularly among Anglophones in Rome and those in positions of authority in the Roman Curia. A couple weeks ago, on the anniversary of the first papal resignation in six centuries, this pithy post showed up in my newsfeed:

..Two year’s ago today, Pope Benedict XVI announced his resignation.

Thus beginning the craziest two years of our lives.

Papa Bennie, we miss you. …

I respect Pope Benedict, perhaps even more so because of his strength of character, as witnessed by the resignation itself. His ecclesiology and personality were both strong enough not to buy into the false mythology of a papacy that is more monarchy than episcopacy, or that requires clinging to power rather than absenting oneself from service when no longer able to serve well.

We all find resonance with different leaders, whether bosses or politicians, bishops or popes. It is natural that some people will like one more than the other, but I have a hard time understanding those who claim to be “confused” by Pope Francis, or who think that the last two years have been difficult for the Church.

A recent conversation with friends revealed, of course, those not satisfied with Pope Francis: On one side, the traditionalists who were given the keys to the kingdom under Benedict are now back to being treated as a minority in the Church – which is only fair, as they are, but I can commiserate with the feeling. On the other, genuinely liberal Catholics tend to be unhappy with the Holy Father’s language on women, not sure whether referring to (lay and religious) women theologians as “strawberries on the cake” is meant to indicate that they are mere decoration, or something more appreciative.

Neither side is confused: they know clearly what they do not like. Whether I agree with either side, they know where they stand and I respect that. It is the commentators claiming “confusion” who are not to be trusted. There is nothing confusing at all about a gospel message of mercy and humble service.

Nevertheless, for the broad swath in between liberals and traditionalists, the last two years have been like fresh air after decades of sitting on a Roman bus, stifling because the old-school Italians refuse to let the windows open lest we get hit by moving air and therefore damage our livers. Somehow. (What is the ecclesiological equivalent of a colpo d’aria?)

If the Good Pope opened the windows of the Church at Vatican II to let it air out a bit, it seems much of the trajectory of the last decades has been, if not to outright close them again, to pile up so many screens and curtains that the effect is nearly the same. Francis has opened it again to let the light and fresh air in. Sure, the dust gets blown about that way, but blame it on those who let the dust gather, rather than the one who starts the spring cleaning!

To be fair, if not concise, the analogy would extend to Benedict having attempted the same, only to discover that he did not have the strength. (Though, after years of investing in multiple layers of curtain lace, you ought not be surprised at the surfeit of suffocating material you then have to remove to get at the ‘filth’ hiding in the darkness provided thereby. But I digress.)

I have little doubt that Pope Benedict will be a Doctor of the Church someday, and in addition to his massive corpus of theological writings, his act of spiritual humility and demonstration of truly sound ecclesiology by resigning as bishop of Rome will be the reason it happens.

I have lived through two of the greatest papacies in recent centuries, but if there has been a truly good pope in my lifetime, it is Francis. Two years is nowhere near enough, may he live for twenty more, sound of mind and body, and bring to closure the reforms started fifty years ago. It is perhaps our best hope for unity in the Church, which in turn is the best hope for an effective witness to the Good News.

Mapping the College of Cardinals

With a class this week explaining the college of cardinals and other aspects of the Catholic hierarchy to some undergrads, in honor of the weekend’s consistory creating 20 new princes of the Church, I found a few helpful resources worth sharing.

The Vatican’s website has upped its game, in offering some new statistics on the College of Cardinals. You can find lists by name, age, or nationality. Graphs indicating the distribution of cardinals according to the pope that appointed them, the percentage of electors vs. emeriti, or how many serve in the curia. The graph below breaks down membership according to geographical region.

The independent Catholic-hierarchy.com has already updated its lists, which can be sorted by various values.

The incomparable CGP Grey offers some illumination in his clip “How to become pope”, meant for popular consumption.

There are of course more academic articles, historical sources, and ecclesiological treatises, plus reform suggestions that range from adding women cardinals to eliminating the sacred college altogether. There are interviews with the new cardinals (one reporter shared that Italian colleagues were getting bent out of shape upon realizing that some of the new wearers of scarlet did not speak a word of Italian beyond “ciao”.)

One thing I could not find was a map indicating where the cardinals were from. Something to give visual aid to the question of a more globalized Church reflected in a more globalized college. So I created one.

Click on the (scarlet) pins to see basic information about each cardinal.

Residential cardinals – that is, those cardinal-presbyters who are bishops or archbishops of dioceses around the world – are located according to their See.

Curial cardinals – mostly cardinal-deacons serving in the Roman Curia – are located according to their place of birth (and they represent 28% of the total electorate).

There are options to see retired/over-80 cardinals, too, also organized by curia or diocese. Their pins are a lighter shade of scarlet (cough… pink… cough).

A couple of immediate observations, beyond the overcrowding of Italy, were some of the wide open areas without any: No Scandinavian cardinals, none from easternmost Europe or central Asia. For China, only Hong Kong.

In the US, all but one of the diocesan cardinals are from the eastern half of the country, and that even counts the retirees. There is a small corridor from the great lakes to the north Atlantic coast that accounts for the overwhelming majority of North American cardinals, leaving one thinking it might be time to move some of those pins to the likes of Vancouver, Seattle, Denver, Indianapolis or Atlanta. Or, if we want to go peripheral, maybe Tucson, Honolulu, and Juneau.

Would love to hear thoughts,take corrections, or hear it has been used by other teachers.

Reforming the Roman Curia: Next Steps

This weekend, word started getting around that the much anticipated reforms of the Roman Curia were finally ready for delivery – at least a number of them.

Pope Francis met with the dicastery heads this morning to give them a preview of changes, though no official word yet on what they all will be.

What has been announced is that there is a new prefect of the Congregation for Divine Worship, which has been vacant since Cardinal Canizares Llovera was appointed as Archbishop of Valencia at the end of August. The new top liturgist of the Roman curia is Cardinal Robert Sarah of Guinea. Cardinal Sarah has been working in the Curia since 2001, first as Secretary of the Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples, and since 2010 as President of the Pontifical Council “Cor Unum”. The new prefect, like most of his predecessors, has no formal education in Liturgy.

The rest is a bit of informed speculation, and nothing is ever official until it is announced:

Among the long awaited and predicted reforms to the curia will likely be the establishment of a Congregation for the Laity – raising the dicastery dealing with 99.9% of the Church’s population to the same level as the two (Bishops and Clergy) that deal with the other 0.1%. The new Congregation would have, it seems, five sections: Marriage and Families; Women; Youth; Associations and Movements; and one other. Too much to hope it would be for Lay Ecclesial Ministry? The current Council has a section on sport, so perhaps that would be maintained, but I suspect not.

No one would be terribly surprised to see the new prefect of such a congregation turn out to be Cardinal Oscar Andrés Rodriguez Maradiaga of Honduras, since he suggested the move publicly last year. What would be a true sign of reform would be to appoint a lay person or couple with degrees and work experience in lay spirituality, lay ministry, or something related. Then make the first lay cardinal we have seen in a century and a half.[1]

The new congregation would certainly combine and replace the Councils for Laity and for Family, but could possibly also incorporate New Evangelization or Culture, which are directly related to the apostolate of the laity in the secular world.

If you read Evangelii Gaudium, though, it is clear that Pope Francis sees the “new Evangelization” as an aspect simply of Evangelization proper, and I would be less surprised to see this Council incorporated into the Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples. Culture would be appropriately aggregated to Laity.

The other big combination long anticipated would be a Congregation for Peace and Justice – or something similarly named. It would combine the Councils of Peace and Justice, Cor Unum, Health Care Workers, and the Pastoral Care of Migrants and Itinerant Peoples, and possibly the Academy for Life. It would have sections corresponding to these priorities: Life; Migrants; Health Care; Charity; and Peace and Justice in the World. Presumably, Cardinal Peter Turkson of Ghana would continue from the current homonymous council as the prefect of the new Congregation.

Finally, a revamp of the Vatican Communications apparatus has been underway for a couple of years, and we could expect to see something formal announced much like the Secretariat for the Economy. Perhaps a Congregation for Communications, or at least a stronger Council, with direct responsibility all communications in the Vatican: L’Osservatore Romano, Vatican Radio, CTV, the websites, various social media, the publishing house, etc.

Now, a couple of ideas that would be welcome, but are not expected:

The combination of the Congregations for Bishops and Clergy – have a single congregation with three or four sections: Bishops, Presbyters, Deacons, and Other Ministers/Lay Ecclesial Ministy. This would be especially possible if the responsibility for electing bishops – only in the modern era reserved to the pope – could be carefully restored to the local churches in most cases.

The creation of a Congregation for Dialogue, replacing the Councils for Promoting Christian Unity, Interreligious Dialogue, and the Commission for Religious Relations with the Jews. It would accordingly have several sections: Western Christians; Eastern Christians; Jews; Other Religions. Perhaps the whole Courtyard of the Gentiles effort could be folded into this as well.

Alternatively, leaving Ecumenism and Interreligious Dialogue in separate dicasteries but with more influence, like requiring every document coming out of the CDF and other congregations to be vetted before publication, to make sure they incorporate ecumenical agreements and principles as a sign of reception.

Formalization of the separation out from the Secretariat of State for responsibilities relating to moderating the curia. The Secretariat should be dealing with diplomatic issues. The rest could be reorganized in a number of different ways.

Streamlining of the judicial dicasteries, including removing the judicial aspects out from CDF and into a stand-alone tribunal. Granted, it is thanks to then-Cardinal Ratzinger and the CDF that any movement on abuser priests happened, but it is still anomalous to have. (Still need to work out what this would look like though).

A consistory which creates no new Italian cardinals – lets get the numbers down to a reasonable amount. Like five. If there are any (North) Americans, they would be the likes of Bishop Gerald Kicanas from Tucson, Archbishop Joe Tobin of Indianapolis, or Archbishop Peter Sartain of Seattle – but nobody else from east of the Mississippi. Maybe a bishop from Wyoming or Alaska, the real “peripheries” of American Catholicism. At least five Brazilians and another Filippino. Maybe an Iranian.

Above all, nobody would be appointed to serve in a dicastery without a doctorate in the relevant field, and experience in that area of ministry.

——

[1] The last being Teodolfo Martello, who was created cardinal while still a lay man, though he was ordained deacon two months later. At his death in 1899, he was last cardinal not to be either a presbyter or bishop. Since 1917 all cardinals were required to be ordained presbyters; since 1968 all were normally required to be ordained bishops.

Married Catholic Priests Coming to a Parish Near You

Pope Francis has moved to allow more married Catholic priests.

It is just that they are not Roman Catholic priests.

This, according to a document of the Pontifical Congregation for Oriental Churches, leaked today by Sandro Magister, the well-known Italian Vaticanist of La Repubblica.

The Congregation has issued a precept, “Pontificia Praecepta de clero Uxorato Orientali” – signed back in June and with papal approval– which allows the Eastern Churches to ordain married men wherever the Church is found, and to bring in already married priests to serve as needed, throughout the world. [6/106 Acta Apostolica Sedes, 496-99]

Most people know that Catholic priests of the Latin Church (the Roman Catholic Church) must be celibate. The exceptions being, since the 1980’s, former Lutheran or Anglican clergy who come into full communion, who may continue their presbyteral ministry while married.

Most Catholics are at least vaguely aware that this medieval discipline does not apply to most of the 22 Eastern Catholic Churches, who do in fact allow married men to become presbyters – it is only their bishops who are necessarily monastic, and therefore celibate. (Deacons are universally allowed to be either married or celibate).

Fewer people are aware of the embarrassing history that has restricted these churches from either ordaining married men “outside their traditional ritual territory” or, in some cases, even sending married priests to serve in these countries. Starting with migrations of Ruthenians in 1880 to the U.S., the Latin bishops (almost entirely Irish) of the States were so scandalized by the idea of married presbyters that they convinced the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith to restrict married clergy from following their flocks to the new world. By 1929-30, these limitations were repeated and even expanded to other “Latin territories”.

This move so effectively undercut the sacramental ministry and infrastructure of the Eastern Catholic Churches in the States, that about 200,000 Catholics and their married clergy left communion with Rome, and effectively populated the Orthodox Church of America and other Orthodox jurisdictions.

This is one of many examples of a kind of aggressive Latinization – forcing Eastern Churches to take on Latin/Roman practices – that has occurred over the centuries. The whole idea that Eastern Churches could only follow their own practices within their “traditional territory” is dubious in any case – do we say the same for the Roman Catholics? Is celibacy of diocesan clergy – a particularity of being “Roman” not of being “Catholic” – limited only to the “traditional territory” of the western Roman empire? What sense does it mean in an era when there are more Eastern Catholics outside “traditional territory” than within?

What it really shows is a flawed ecclesiology and a lack of due respect to the autonomy of the diverse practices and patrimony of ancient and apostolic churches in communion with Rome. How, our Orthodox sister churches would ask, is it possible to take Rome seriously on proposals for reunion when she treats Eastern Catholic Churches so inappropriately – flexing her muscles and forcing them to follow her whims (or those of too-easily-scandalized Irish-American bishops). Rome has to show that it remembers that unity does not mean uniformity.

After Vatican II, it was thought this would change. After all, the Eastern Churches were encouraged to return to their proper patrimony and cleanse themselves of any inappropriate Latin influences. Pope Paul VI took the proposal under advisement… and there it remained, sadly, until our own time. The Congregation for Oriental Churches proposed some change in 2008, but with the objection of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith to reversing the ban, exceptions were allowed only on a case-by-case basis. You started to see priests ordained back in the “traditional territory” being allowed to serve in the west. Under these “exceptional” situations, it was just this year that the U.S. saw its first married Maronite priest ordained there.

In 2010 the Synod on the Middle East again raised the issue.

Now, finally, we have the restoration of at least this one right to rites.

The Eastern Churches find themselves in three jurisdictional situations, basically, which have different practical consequences:

- First, where there is a regular hierarchy, it is up to the competent ecclesiastical authority – the metropolitan, eparch, or exarch – to ordain according to the traditions of their churches, without restriction from the Latin church.

- Second, where there is an Ordinariate without a bishop or heirarch, such ordinations would be carried out by the ordinary, but while informing the Latin hierarchy. (there are less than a half-dozen countries where this is the case)

- Third, where there are groups of the faithful of an Eastern Church under the pastoral care of a Latin ordinary – such as the Italo-Albanians here in Italy – it continues to be a case-by-case basis.

Still, one more reform on the long list of “no-brainers” that could have been done ages ago without actually challenging either doctrine or even its articulation. It is simply the correction of an historical mistake that ought never have happened in the first place – and certainly ought not to have taken 135 years. It is this kind of thing, no matter how small, that demonstrates real “concrete progress” that the ecumenically minded – both “at home and abroad” are looking for.

Link to Magister article: http://magister.blogautore.espresso.repubblica.it/2014/11/14/francesco-da-il-passaporto-ai-preti-sposati-orientali-valido-in-tutto-il-mondo/

Cardinal Burke

Since September, it seems nothing has been bigger news in the circles of ecclesiastical gossip and intrigue, especially for the aficionados of the Tridentine liturgy, than the rumored “demotion” of Raymond Cardinal Burke, a Wisconson native and former Archbishop of St. Louis, who has been serving as Prefect of the Apostolic Signatura since 2008.

Radical Traditionalists, already no fans of Pope Francis, immediately went into hyperbolic fits of indignation: Never has a cardinal been treated so badly! What disrespect! How ham-fisted! It’s a junta! You might as well decapitate him! Where is Pope Benedict? Or Pius X, better yet? This is all Kasper’s fault! Woe is us! The modernists are coming!

Naturally, the secular media picks this up from the conservative Catholic blogosphere and puts their own spin on it: Burke is demoted for opposing reforms in the Synod; Burke is demoted for calling the Church rudderless under Pope Francis; Burke is demoted for disagreeing with Pope Francis on LGBT issues, etc.

Though he confirmed the rumor himself in the midst of the Synod on the Family, the official appointment was only made on 8 November, when Burke was appointed as Cardinal Patron of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta – a crusader-era hospitaller order that continues its millennium-long tradition of service and chivalry from its headquarters on Rome’s Aventine hill.

But the truth is, if Pope Francis were really interested in ungraciously demoting Burke, he could remove him from the College of Cardinals altogether, send him into cloistered retirement permanently, or appoint him as bishop of some small diocese somewhere (I hear Spokane is open).

The fact is that nearly all the cardinals working in the Roman Curia as heads of dicasteries lose their office when the pope that appointed them dies or resigns. The new bishop of Rome has complete freedom to either confirm them in their appointments, reappoint them anew, give them a temporary appointment, or let them go altogether. All cardinals are basically at-will employees of the Pope – more so than any other office in the Church, the Sacred College is tied directly to the personal prerogative of the bishop of Rome.

Cardinal Burke was never confirmed in his office as prefect, but was simply left there on an interim basis – even for longer, at 18 months, than several others in the curia. This happens with every single new pope. All the time.

Far more dramatic moves are common. Some quick examples:

- About ten months after his election, Pope Benedict XVI effectively combined two Pontifical Councils – Culture and Interreligious Dialogue – under the leadership of a single president, and sent the former president from Interreligious Dialogue out to the nunciature in Cairo, without the dignity of the red hat that usually goes with his former office.

- Pope St. John Paul II was known to be heavy-handed with bishops in a way that neither Francis nor Benedict can be said to emulate. In the 80’s he placed the Archbishop of Seattle in a bizarre power-sharing arrangement with a freshly minted auxiliary bishop (not a coadjutor) for a year. In the 90’s he appointed a French bishop to a diocese that has not existed for fifteen centuries, just to force him out of any pastoral responsibility.

- Pope Bl. Paul VI transferred one bishop who opposed reform efforts from being ordinary of a diocese to serving as auxiliary of another.

- Pope St. Pius X, of course, is rumored to have simply pulled the zucchetto off the head of a bishop he did not like, sending him off with a “Goodbye, Father” to indicate his demotion to presbyteral status. (which flies in the face of Catholic ecclesiology, after all: ordination leaves an indelible character, no?)

By comparison, Burke is being given a plum assignment. He gets a cushy residence, gets fêted and fed, gets to dress up in his beloved baroque wardrobe, and never has to worry about his livelihood. On top of that, he actually gets to work with an established and internationally respected humanitarian organization. I would not mind being “demoted” like this. Not at all. (Except for the garb, i suppose).

By comparison, Burke is being given a plum assignment. He gets a cushy residence, gets fêted and fed, gets to dress up in his beloved baroque wardrobe, and never has to worry about his livelihood. On top of that, he actually gets to work with an established and internationally respected humanitarian organization. I would not mind being “demoted” like this. Not at all. (Except for the garb, i suppose).

Cardinal Burke served for just over six years as prefect of the Apostolic Signatura – longer than any of his seven predecessors going back to the days of Paul VI.

It is true that he has become the poster-bishop for the Extraordinary Form of the Roman Rite – the Tridentine Mass. He is more widely known for his watered silk and lace ensembles than for his various canonical accomplishments. He is outspoken in his criticism of even the slightest suggestions at reform in the church, a voice for the status quo and the fortress-against-the-world approach to ecclesiology.

This is not the message the Church should be sending. Noble simplicity does not call for acting simply like nobility. The Church does not need princes in renaissance and baroque regalia, it needs shepherds and servants garbed like Christ the Deacon, ready to wash the feet of the disciples of God.

It seems somehow fitting to match Burke with the Sovereign Military Order of Malta. An affinity for flashy capes is perhaps not their primary charism, but it is a starting point that they share with their new patron. It can be done in context, not as an historical recreation or an exercise in liturgical nostalgia.

Does anybody think he would be better suited at Cor Unum or Christian Unity? Archpriest of Mary Major? Or perhaps as a diocesan ordinary back in the States somewhere? Personally, I wonder why there is not just a personal prelature for the devotees of the Extraordinary Form; make Burke the prelate. Or perhaps personal ordinariates might be more fitting; make him one of the ordinaries. If there is one bishop (in this case a cardinal) representing that movement in the church, it would be enough. If it is that ministry which gives him the most joy, and for which he gets the most support, would not that be just the place to put him?

On Priestly Celibacy and the Diaconate

This has been on my mind since the first minor flurry of stories about Pope Francis’ openness to discussion on the topic, based on the recounting of a single remark shared by Bishop Erwin Krautler of the Territorial Prelature of Xingu, Brazil. So, it is a lot of musing, but enough to get some conversations started, I hope.

First, an aside about numbers. Most accounts, like the RNS article linked above, cite 27 priests serving 700,000 Catholics, meaning a ratio of 1:25,925, a staggering reality if accurate.

However, I am not sure where these numbers come from. According to the Annuario Pontificio 2012, there are only 250,000 Catholics there, being served by 27 priests (about half diocesan and half religious), and according to Catholic-hierarchy.org, there are 320,000 Catholics (but only as of 2004). This means a ration of either 1:8620 (AP) or 1:13,333 (CH).

Still a staggering reality when you consider as frame of reference the following: The Archdiocese of Seattle, my home diocese, currently lists 122 active diocesan priests, 87 religious priests, and 31 externs borrowed from other dioceses serving a Catholic population of 974,000. This makes a priest to Catholic ratio of 1:4058 (the US average is just under 1:2000).

The Vicariate of Rome, my current diocese, has nearly 11,000 priests and bishops present, counting religious, externs, and curial staff. They are at least sacramentally available to the 2.5 million Catholics here. This makes a ratio of 1:234.

(Since priests were the subject of the article, I have left out deacons, catechists, and lay ecclesial ministers, as well as non-clerical religious, though not to discount their great service to the Church, to be sure!)

Even with the most conservative estimate of Xingu, the priests there are stretched more than twice as thin as their Seattle counterparts and 36x the scope of their Roman brethren.

What has really been on my mind, though, and again in the light of Pope Francis’ comments yesterday that the ‘door is always open’ to this change in discipline, is the effect that a sudden shift in allowing for a married presbyterate would have on the diaconate.

Some refreshers on basic points of the general discussion:

- We are only talking about diocesan (sometimes called secular) clergy, not religious. The latter would remain celibate under their vow of chastity, but diocesan clergy do not take such vows.

- We already have some married Catholic priests. Almost all of the Eastern Catholic Churches allow for both married and monastic clergy, and even in the Latin Church (i.e., Roman Catholic Church) we have married priests who were ordained as Anglicans or Lutherans, later came into full communion, and have been incorporated into Catholic holy orders.

- We do have celibate deacons, though not many. I have long held we need more celibate deacons and more married priests in the west, for various reasons.

- Most likely we would be talking about admitting married men to orders, rather than allowing priests to marry after ordination. This is the ancient tradition of the Church, east and west, since the Council of Nicaea when it was offered as a compromise between some who wanted celibacy as the norm, and others who thought it should not matter whether marriage or orders come first. We still have both extreme practices present in the Church today, however, so it is not impossible that we should choose a different practice. Unlikely, but possible.

- The Latin Church has maintained celibacy as a norm for its diocesan clergy since about the 12th century, though historians argue whether it was universally enforced until as late as the 16th. There are rituals as late as the 13th allowing for a place in procession for the bishop’s wife.

- Technically, it is currently the norm for all diocesan clergy, and any exceptions, including married deacons, are exceptions. Which begs the question, if it is so easy to make these exceptions for deacons, why not for priests?

- The Byzantine tradition has long held that bishops come from the monastic (celibate) clergy, whereas the Latin tradition has long held that bishops come from the diocesan clergy – which means we had married bishops when we had married priests and deacons. Given the situation with the Anglican Ordinariate, there seems to be a reluctance to return to this tradition, but as it was part of our Roman patrimony for a millennium, it seems it should be at least considered.

- Finally, it is not actually clerical, or priestly, celibacy per se that is at issue, but the idea of requiring celibacy of those to be ordained. There will always be room in the church for celibate deacons, presbyters, and bishops, and these charisms will always be honored. As it should be.

With all that in mind, I finally get to my point.

Let us imagine, unlikely though it may be, that tomorrow Pope Francis announces we will no longer require celibacy of our candidates for orders – whether deacon, presbyter, or bishop. The most immediate effect and response of the faithful, and the press, will be about the change in the discipline of priestly celibacy.

If it is done that directly, it would be disastrous for the diaconate. Many men, I have no doubt, have been ordained to the diaconate simply because they or their bishops saw no alternative for someone called to both marriage and ordained ministry. Many may in fact be called to the presbyterate instead, and given the opportunity, ‘jump ship’ from one order to the other.

One can likewise imagine there are many currently in the presbyterate who are actually called to the diaconate, but they or their bishop saw no reason for not ordaining them to the presbyterate because they were called to celibacy as well. I have heard many a bishop say something along the lines of, ‘why be ordained a celibate deacon? If you can be a priest, we need that more!’

Without completing the restoration of the diaconate as a full and equal order, and a better understanding of both orders separated out from the question of marriage/celibacy, what will happen is a return to the ‘omnivorous priesthood’ and an ecclesiology of only one super-ministry. Rather than a plethora of gifts and ministries as envisioned in the Scriptures, lived in the early church, and tantalizingly promised at Vatican II, everyone would flock to the presbyterate and we would have set back some aspects of ecclesiological reform half a century.

Rather than simply a change to the discipline of clerical celibacy, what is needed is a comprehensive reform of ministry in the Church. Tomorrow Pope Francis could say, instead, ‘Let’s open the conversation. Over the next three years, we will look at the diaconate and the presbyterate, lay ecclesial ministry and the episcopate, and we will consider the question of celibacy in this context. At the end of this study period, a synod on ministry.’

What I would hope to come out of this would be first a separation of two distinct vocational questions that have for too long been intertwined: ecclesial ministry on one hand and relationships on the other. We have been mixing apples and oranges for too long, but priesthood or diaconate is an apple questions, and marriage or celibacy is an orange question.

The deacons, traditionally, are the strong right arm of the bishop. Make it clear that deanery, diocesan, and diplomatic tasks (and the Roman curia for that matter) are diaconal offices. In need, a qualified lay person could step in, or rarely a presbyter, but these are normatively for deacons. This also makes it obvious why we need more celibate deacons, such as in the case of the papal diplomatic corps. They tend to be younger and more itinerant, needed wherever the bishop sends them.

Presbyters are traditionally parish pastors and advisors of, rather than assistants to, the bishop. As the deacon is sent by the bishop, the pastor ought to be chosen from and by the people he serves.. He should be a shepherd who smells like his sheep, right? How exactly this looks can take various forms, to be sure the bishop cannot be excluded, but the balance of ministerial relationships should show clearly that the presbyter is more advisor to the bishop and minister among the people he is called to serve, and the deacon is the agent of the bishop. At least one should not be ordained until there is an office to which he is called which requires his ordination This also makes it obvious why presbyters can, and often are in other churches, married. They tend to be more stable and older.

The minimum age for ordination should be the same for both orders, regardless of marriage or celibacy, and in general one can imagine that deacons would be younger than presbyters. Let the elders be older, indeed!

Some deacons may even find, later in life, reason or office to transition to the presbyterate, but otherwise there should be no such thing as a transitional diaconate. Candidates for both orders should spend at least five years, perhaps more, in lay ecclesial ministry, before being ordained, as long as this does not reduce lay ministry to a transitional step only, as a similar move did to the diaconate all those centuries ago!

Bishops could be chosen from either order, and be either married or celibate. Indeed, celibacy should be rejoined with the rest of the monastic ideal, and there should be no such thing as a celibate without a community. It need not be a community of other permanent celibates or of other clergy – there are some great examples, such as the Emmanuel Community in France, who have found ways for celibate priests to live in an intentional Christian community that includes young single people, deacons, lay ecclesial ministers, etc.

Bottom line, if it is just a conversation about priesthood, as much as mandatory celibacy needs to be discussed openly and without taboo, it is not enough. It must be a holistic discussion about ministry, and the diaconate has a special place in this conversation given its recent history and current experience. We have such a deep and broad Tradition from which to draw, why would we not dive in to find ancient practices to suggest modern solutions?

The WYSIWYG Pope

What I like most about Pope Francis is probably his integrity. Honesty and humility wrapped up with transparency. This is exactly what some people seem to find most frustrating – the off-the-cuff remarks, open to interpretation, or occasionally without all the details in place. The WYSIWYG Pope (What You See Is What You Get). But that is precisely the charm. And a much needed breath of fresh air. Just as Benedict XVI was a different kind of fresh air after the long lingering of John Paul II, and his theological acumen and teaching gifts a welcome change from the poetic philosophy of our most recent sainted bishop of Rome, the straight-shooter Francis is a welcome change from the meticulously careful German academic.

What I like most about Pope Francis is probably his integrity. Honesty and humility wrapped up with transparency. This is exactly what some people seem to find most frustrating – the off-the-cuff remarks, open to interpretation, or occasionally without all the details in place. The WYSIWYG Pope (What You See Is What You Get). But that is precisely the charm. And a much needed breath of fresh air. Just as Benedict XVI was a different kind of fresh air after the long lingering of John Paul II, and his theological acumen and teaching gifts a welcome change from the poetic philosophy of our most recent sainted bishop of Rome, the straight-shooter Francis is a welcome change from the meticulously careful German academic.

I am still unpacking all the ecumenical and interreligious activity of the weekend, but some small examples suffice as well. During his interview on the plane, Papa Francesco again responded to questions about celibacy, stating ‘nothing new’ when he said that the door is (theoretically) open, as required celibacy for diocesan priests is a discipline and not doctrine or dogma. Many have said it before and anyone who has studied Church history or understands the hierarchy of truths knows this and is probably thinking, “Just words… I’ll believe it when I see it.”

But whether he is talking about celibacy, or clericalism, or retiring popes, he is willing to speak directly on subjects that have been largely taboo for the rest of us for the last generation. I am not talking about ‘liberal’ issues like changing church moral teaching, ordaining women, or embracing New Age spirituality as a replacement for the rosary. I am talking about centrist, orthodox, reform issues like creative responses to our ministry problems drawn from the Tradition of the Church. This is about healing wounds caused by scandal and sex abuse, and demolishing systems that promoted or allowed such to happen, and build up in their place living adaptations of even more ancient ecclesiological structures.

Pope Francis is willing to name these problems, and at least open them up for discussion. Hopefully that attitude will trickle down, like a bad economic model (or perhaps, like the dewfall), to the rank and file church leadership, and we will have a vibrant discussion on how best to support our priests, bishops and deacons without enabling clericalism; how to support celibacy as a charism without foisting it on anyone with a call to ecclesial ministry and leadership; and how to accept that the bishop of Rome is not a monarch for life by divine right, but a diakonos of the diakonoi of God.

Reflections after a hiatus…

For the next few weeks, I will be perched in a loft suite in what was once the Monastery of St. Andrew, founded by Pope St. Gregory the Great. For its more recent history (a mere millennium or so), it has been under the care of the Camaldolese Benedictine monks.

Working with both US and Roman academic systems once again, several of my jobs have finished for the year – undergrad professor, TA, and residence manager – while others continue for a few weeks: seminary professor, John Paul II Center graduate assistant. With no more undergrads in residence to manage, I have had a week to clean up and vacate myself. For the intervening few weeks while finishing other tasks, this view is mine. Then plans for a little travel in Italy, a three week seminar on Orthodox theology in Thessaloniki, and a few stops in North America before coming back for a new semester in late August.

When I opened my draft file for the blog, I found 15,000 words in notes waiting for me. I should be so inspired on my doctorate! (The oldest is a half written post about the feast of St. Agnes, well known for the blessing of the lambs to be shorn for wool used in the making of the pallium – the unique vestment of metropolitan archbishops everywhere. A friend once asked the sisters responsible for the shearing about their fate, these blessed and cared-for critters, “Que successo?” “Al forno!”)

I will see what I can do about resurrecting a few of the choicer bits, but I really ought to be grading a few last papers anyway. I am keeping a file of funny answers, too, for late publication (along the lines of “Vatican II is the pope’s summer residence, right?”)

What a year it has been, too! I remember a monsignorial staffer under JPII once claiming that the curia were constantly “out of breath” trying to keep up with the then-tireless pontiff. Communications fiascos notwithstanding, one begins to think the Benedict years were something of a breather for them. Now, each week brings something new and interesting for the vaticanisti and the ecclesiology wonks.

Pope Francis is not quite my idea of a perfect pope, but he is the pope I think I have been waiting for, for most of my life. A colleague asked me recently what I thought about him, and opened by suggesting she thought I might be more of a Pope Benedict fan.

It is true, in many ways: my personality is more similar to Ratzinger than either Wojtyła or Bergoglio. I appreciated Ratzinger’s profound theological acumen and ecumenical commitment, his ability to listen, his collaborative style and loyalty to his close collaborators. A lot of pastors and bishops could learn from that example.

He was the first real theologian-pope in a couple of centuries, and in terms of prolificacy, stands among the greats. His sensitive, introverted, and bookish personality made me think that, if I had to choose a kindred spirit from among the three pontiffs which I can remember during my lifetime, it would be Ratzinger. (I was born in the last months of Paul VI, and still in diapers when John Paul I had his brief time on the Chair of Peter).But, the Church is in need of reform. It is always in need of reform, always in need of purification. While John Paul II and Benedict both lead certain areas of reform forward, certain ecclesiological and very practical issues have remained untouched.

The Roman curia and its communications stagnated under John Paul II, the quality and confidence of bishops and bishops’ conferences waned, and a centralized ultramontanist ecclesiology crept back in – really, had never quite been rooted out – but both were overshadowed by the sheer volume of his personality. Under Benedict, many of the inherited flaws began to show through, and he unfairly got much of the blame for issues that went without redress under his saintly predecessor. The sex abuse scandal sits at the top of the heap, finances next, but the whole Vatican communications apparatus was not far behind. Pope Benedict got the ball rolling in many cases – on sex abuse, on finances, on Vatican personnel – but these successes were frequently given short shrift compared to the communications and competence fiascoes. The biggest distraction was unfortunately his ecumenical effort at reintegrating traditionalist sects into the Church via a re-introduction of the Tridentine liturgy on a mass scale [pun intended].

I think I understand Ratzinger’s concern with the abrupt changes to the liturgy in the late sixties. One of his main themes has been about a reintegration, an informing of each other, of the old Tridentine Rite (what he called the Extraordinary Form of the Roman Rite, the Mass of Pius VI (1570), Revised in 1962) and the ordinary form of the Roman Rite (the Mass of Paul VI, Missal of 1970, last revised in 2002). Aside from the fact that this seems to make Ratzinger a champion of the hermeneutic of discontinuity that he otherwise preached against, for many people the revival of the baroque bling in liturgy was a distraction at best, and a sign of a return to the disastrous ecclesiolatry of the late 19th and early 20th century at worst. Not without reason, for too many people in the Church, the high baroque trappings, the traditionalist interpretation of liturgy, the lace and the maniple et al. all go hand in hand with precisely the forms of clericalism and institutional navel-gazing that allowed the scourge of pedophilia to fester and actually promoted the kind of bishops who would cover up the worst cases.

This association is not one Ratzinger could make, and it is his papacy that convinced me it is not an entirely fair association, either. To him and to many of his fans, there was a certain kind of reverence lost after 1968 that had to be retrieved, and his own personal piety found its comfort zone, like most of us, in the mode of expression he was familiar with in the innocence of childhood. Indeed, in my first few years in Rome, many curial officials bemoaned the ‘crisis of 1968’ as if everyone should know what it was, and somehow never seemed to understand why I (and many of my peers) found it shocking that someone who lived through 1938 could think that 1968 better represented the downfall of moral society!

The real problem was that he was trying to put the toothpaste back in the tube, so to speak, forty years too late. It might have been a better way to go immediately after the council, to have a slower, longer transition period, maybe with both forms of the rite for a period of time. But now, given the state of the church he inherited, and indeed had some responsibility for, what the Church needed was, and is, great reform. And it needs to be seen making this reform with urgency and integrity. Pope Benedict started some much needed reform, but more attention was given to the moves that seemed to be contrary to reform – even if that was not entirely his intent. It is Francis who is seen to mean it, without qualification and without pining for a long lost ideal that was not nearly so ideal as it seems now, to some. And he has the energy to engage it full-on. If only he were twenty years younger!

The most commonly spoken fear in Rome, these days, is that Francis will be assassinated (a la Godfather III) before his reforms can take effect. It is mostly said jokingly, in a moment of black humour.

The real fear and the reason that even a year after his election there is only a subdued hope and enthusiasm is this: We had a Council. We had every bishop in the world come together and call for reform; for greater synodality and collegiality; for a renewal of the diaconate and appreciation for the vocational contribution of the laity; for uncompromising commitment to ecumenism and interreligious dialogue; and commitment to being in, if not of, the modern world; for a renewed and constantly renewing liturgy that called forth full, conscious, and active participation.

Yet, at the fiftieth anniversary celebration of the opening of Vatican II in Rome, one participant quipped ‘it seems as if I have come to a funeral, rather than a celebration. Are we here to honor the Council, or bury it?’ Everyone one of the reforms I mentioned was floundering or at least seemed to be unpopular in the halls of power and in the seminaries. “Ecumenism?” I heard one priest say, “They will never make you bishop doing your license in ecumenism. Try dogma or canon law. Ecumenism is a failed experiment anyway.” Within a couple decades of the largest and most comprehensive ecumenical council the Church has ever seen, some of its central acts were being re-interpreted in ways to make them less like reform and more like reinforcement of the old status-quo.

Many reforms remain half-executed. Just by way of example, take the restoration of the diaconate as a full and equal order – while we now have permanent deacons, we still have transitional ones as well. The cursus honorem of the seminaries, in the minor orders, though officially abolished, has since the early 80’s has been effectively revived with nothing more than different names and rites. Most people think the major difference between deacons and presbyters is marriage and celibacy, meaning there is no shortage of men called to the diaconate being ordained priests, and men called to priesthood being ordained deacons. And nobody agrees on just what a deacon IS, though too many people assume they are subordinate to priests. Yet there has been very little official movement, and not even the possibility of discussing ordination and marriage in the same sentence, in fifty years. It has even become en vogue to revive the befuddled medieval thought that deacons are not really clergy anyway, since they are not ordained to the priesthood, as such.

If the Council could not achieve a comprehensive lasting reform in all of the intended areas, the thought goes, how can one pope? Especially one who may serve for a decade or less? Will he not so disturb some of the powers-that-be, that when his successor is elected, they will seek to balance the ‘fast-moving’ years of Francis with another caretaker pope? People talk of pendulum swings as if John Paul II and Benedict were conservative and Francis liberal, when in fact Francis is just the middle ground where the pendulum should come to stop and rest.

If we have a century of popes in the mode of Francis (and John Paul I, I suspect), we might be able to fully receive the Council without the continued polarization of the Church in the last five decades. We might be able to fully live out the reforms called for, without undue excess or burdensome reticence, and collectively take joy in being the Church again.

As one of my students recently said, “Pope Francis made it cool to be Catholic.” For her, it was the first time in a lifetime of faith that this was the case; when I shared this with an older student later, he simply smiled and added, “…again.”

Church reform and papal retirement, a year on

John Allen’s article commemorating the first anniversary of Pope Benedict’s resignation this week points out that for all the attention Pope Francis has received this year as a ‘revolutionary’ or ‘reformer’, the single most revolutionary act by the bishop of Rome in the last year was Benedict’s humble and courageous decision to retire.

Even here in Rome, studying at the heart of the Church, I found out first through Facebook.

It is a great example of something that should not have been surprising, or all that revolutionary. Certainly, it was, given the climate and context of the Church in recent decades. Following on the heels of the soon-to-be saint John Paul II, who lingered in office several years longer than was probably good for himself or for the Church, one might have thought it was blasphemous to suggest something of the sort. In a sense, Benedict, being the excellent ecclesiologist that he is, had to resign, to disabuse the papacy from the personality cult, and remind us that every office in the Church is one of service and ministry; not power, prestige, or persona.

The impact on the conclave was obvious, as many commentators have already noted. Rather than an overwhelming outpouring of grief at the death of the towering figure of John Paul II that got his right-hand man elected, the cardinals were able to take better stock of the real situation in the Church and especially in the curia, and set about doing something about it.

It never ceases to amaze me how strong the current is that was in favor of the retreat from reform (sometimes called a ‘reform of the reform’) in a Church that has declared, a the highest level of authority, ecclesia semper purificanda. The truth is that there is no purification without reform; there is no reform without action. We must act to change the Church, so that the Church can change the world.

For the last generation, we have been told repeatedly that ‘tinkering with Church structures’ is not what is needed; instead, greater personal holiness is the all-encompassing solution. There is both wisdom and naivety in such statements. The wisdom is that prayer is paramount, and holiness is indeed a necessary virtue in all Christians; the naivety is that tinkering is not what is needed not because it is ineffective, but because some structures have been so badly neglected for so long that any ‘tinkering’ is just putting lipstick on a pig. Anything short of a radical and all-encompassing overhaul is complicity, or at least complacency.

But in a sacramental reality, we cannot underappreciate the real value of a change in tone; we cannot dismiss it as superficial. Which is not at all to buy into the oversimplified dichotomies we see, both in secular media (e.g.Rolling Stone) and in the reactionary wing of the fold that contrast Benedict and Francis, putting one or the other in a completely unfavorable light.

It has always seemed to me that Benedict’s biggest liability was not (just) a hostile secular media who never let go of the image of God’s Rottweiler – because in truth, his biggest fans never did either, still hoping for the hammer of heresy to drop. It was about image, though: His apparent penchant for baroque bling distracted from his genuine reform efforts.

For too many in the church, these trappings of power and privilege – whether imperial, renaissance, or baroque in origin – go hand in hand with clericalism and the sex abuse scandal. Who can forget that it was the church of lace surplices, brocaded maniples and mumbled latin anaphorae – with its concomitant failure at human formation in seminaries and warped ecclesiology – that brought us the greatest wave of scandal the Church has faced in the modern age? It does not matter that there is little or no direct causal relationship, but the correlation is too widely fixed: “traditionalism” = clericalism = abuse of power = a climate of permission for child sex abuse.

Joseph Ratzinger had long been trying to redeem that, to separate out the legitimate traditions from their accrued associations. He may have a point that the transition from the Missal of Pius V to that of Paul VI was too abrupt, but his solution came forty years too late. Add that to his well-established reputation and the series of administrative and communications fiascos, and there was only so much he could do.

So he did what he could: he set the stage for someone without the same baggage to come along and continue the good work he had started. I can imagine that he realized the cost of trying to restore some place in the mainstream for the older form of the liturgy came at too high a cost, or that the cause of reunion with the SSPX was lost. Or perhaps he saw his work done already: he brought the tridentine liturgy out from the periphery and into the center of the Church, in whatever small way. He left no more excuses for “traditionalism” to be a code word for dissent, and planted the seeds that may redeem that part of our liturgical patrimony from its oft-associated failures in ecclesiology, pastoral formation, and leadership.

Thanks to Pope Benedict, contemplation and action could again meet in the endless effort of Church reform. There is much to be done, since, in some respects, the Church stopped being interested in self-purification and reform sometime around the time I entered adolescence, as if the whole idea had been a failed experiment of the 70s and 80s rather than a movement of the Holy Spirit.

Enter Pope Francis, who genuinely seems to be setting about to reform the Church, perhaps (we can hope) on as grand a scale as Gregory I or VII, Pius V, or John XXIII. Some will call anything he accomplishes too little, too late; others will denounce it as too much, too fast. I would instinctively err on the side of the former, considering how many centuries it often takes to resolve problems in this institution, but in the last year it has been hard even to keep up with the constant flow of good news. I continue to pray for deep, genuine, and theological reform of the Church, and I have hope that it is coming. The Church is, after all, called to be holy, too, not just the people in it!