Home » Posts tagged 'clericalism'

Tag Archives: clericalism

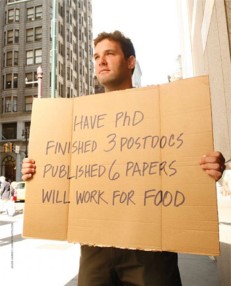

If I wanted to be wealthy, I should have been a priest

What is missing in the 2017 National Diocesan Survey on Salaries and Benefits for Priests and Lay Personnel? (Commissioned by the National Association for Church Personnel Administrators [NACPA] and the National Federation of Priests’ Councils [NFPC], it was carried out by the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate [CARA]). The overview seems both modest and comparable to the typical lay ecclesial minister’s income:

If I were a priest, I could probably afford the $795 that NACPA is charging to download a copy of their full study, and find out in closer detail. But as a lifetime lay employee of the Church, I have to take it as a given that the good people at NACPA (mostly lay pastoral administrators) have crunched their numbers accurately and the $45,593 is in fact the median taxable income of U.S. priests. A table of contents is publicly available which indicates what they did (and did not) consider.

What about the untaxable income? What about the things that are hard to quantify but observably make a difference? Or easy to quantify but simply taken for granted? What about the expenses that the lay counterpart has that the priest does not? A penny saved is a penny earned, after all.

A pastor I know complained – often and loudly – that he was paying the lay pastoral staff at his new assignment far too much (A little less than $50,000 per year, less than the state’s average income[1]). To his credit, the pastoral council president, who had been involved in the hiring process with the previous pastor, usually replied that the staff were paid about 1/3 of what they were worth in the private sector, and the young priest should be a little more appreciative.

Fr. Scrooge’s attitude got me thinking about the apparent disparity between compensation for equally qualified people with a vocation to ecclesial ministry.

Look at two people of reasonably comparable demographic – single, no children, with undergraduate and graduate degrees in theology/divinity, committed to a life of ministry in the Church – and consider them in a similar parish, similar ministry, with similar qualifications, experience, and responsibility. One is a priest, the other a lay ecclesial minister.

There is no question the priest in such a scenario is “wealthier” – enjoying a higher standard of living, a nicer house, with greater stability, and less stress about making ends meet. So how does this observable reality reconcile with the apparently low income that priests have, according to the NACPA study? Something is missing.

Considering a few major areas of disparity, we can easily track how those pennies add up, taxable or otherwise.

Education

Source: Mundelein Seminary

In the U.S., the standard education and formation program for a priest is to have a four-year Bachelor’s degree (in anything, really, but with a year’s worth of philosophy and theology at the undergrad level before graduate seminary), and a three-year Master of Divinity or equivalent, plus a pastoral internship year. Most lay ecclesial ministers have something similar, if, of necessity, in a greater variety of configurations.

In one diocese I am familiar with, the entire cost of seminary is covered, at least from pre-theology onward, plus a variable stipend for travel and spending. For college seminarians, the students are accountable for half their cost (which could be covered by scholarships they earned from the university, for example).

The average cost of tuition and fees at Catholic colleges and universities in the U.S. in 2016-2017 was about $31,500, with the highest ones being around $52,000 (Source: ACCU). So let us say the diocese i mentioned is typical, and pays for two years of the undergraduate and all three years of the graduate costs for formation: middle-of the road estimate of $157,500 per seminarian.

An additional spending stipend can range from $2000-$6500 per year depending on where they are in studies. Let us say $4000 a year for ease of calculation. An additional $20,000 brings the educational investment up to $177,500. It would be interesting to see what the actual numbers on this spending are.

The candidate for lay ministry, on the other hand, has to work or take out loans, though in some places some assistance is available. Forty years ago, one could work full time at a minimum wage job in the summer to pay for a year of tuition at a respectable state school, but that has not been true since the 1980s. Despite savings, work-study, scholarships and grants, and, if fortunate, parent contributions, the average graduate leaves with $38,000 in student loan debt after a Bachelors, and about $58,000 all told if they have also a Masters from a private institution, which has to be the case if you have a degree in theology. (Source: Newamerica.org study, Ticas.org). The interest on that, at the standard federal rate of 6% over the life of the loan (twenty years) will add another $19,000 to the total.

So far, in terms of pennies saved and earned, the priest is $196,500 ahead, and ministry has not even begun.

But we are not done: the best and brightest are often called to graduate studies, say, a license in canon law or a doctorate in theology.

Another three years of graduate school for a JCL (or five, at minimum, for a doctorate). In Rome, where tuition is cheap but living is costly and jobs are hard to find, it is easy to contrast the stability and support given to clergy with the complete chaos experienced by most laity – who, nevertheless, sacrifice more and more in answer to a vocation to serve the Church.

About $25,000 a year, (choosing the cheaper options of a canon law degree in Rome), and there’s another $75,000 where our priest has uncounted ‘income’.

He is now $271,500 better-off than the lay counterpart …and we are not even counting the little extras Knights of Columbus ‘pennies for heaven’ drives or Serra club gifts.

Note, too, that the priest-grad student continues to draw a salary/stipend, plus other benefits like housing and food stipends, while in studies; the lay minister has to give all this up to pursue studies. According to the study, that means adding another $45,000 per year to the priest’s advantage.

So, make that $406,500 ahead of the lay minister with the same education.

Housing

St. George Parish Rectory, Worcester, MA.

Housing was calculated in the NACPA study, either (or both?) in terms of taxable cash allowances and housing provided, but it is hard to reconcile the low-ball numbers given with the observable reality: Priests living alone in houses that are considerably larger and/or nicer than what their lay counterpart could ever afford to live in. How is this possible?

Simply ask the question: What is the value of the house (rectory) and what would it take to live there?

You can either look at the value of the rectory and estimate the salary required to afford such a place; or you can look at the salary earned and look at how much house someone with that income can afford, and how it compares.

Based on the 2012 CARA survey (being unable to see the 2017 median salary as it is behind a paywall), the median annual salary in 2010 was $34,200. That’s about $38,351 in 2017, factoring for inflation. Assuming no other debts (ha!), that means one could afford a house valued at about $185,000, considerably less than the median price.

The median house value is about $300,000 in the U.S., based on sales prices over the last year (Source: National Association of Realtors). To afford this, one would have to be making about $65,000 a year, at least, and paying $1800 a month mortgage or rent.

But is the typical rectory more or less expensive?

As a point of reference from which to extrapolate, I checked on the value of the rectories in the five parishes where I have lived and worked in the last twenty years. (Source: Zillow). I then compared their value to the median house value in the same cities or regions.

- Everett, WA Rectory Value: $550,000. (Median House: $330,000)

Estimated monthly payment: $3560. Recommended income: $120,000 per year. - Woodinville, WA Rectory Value: $641,000. (Median House $755,000)

Estimated monthly payment: $4366. Recommended income: $146,000 per year. - Bellingham, WA Rectory Value: $700,000. (me Median House: $415,000)

Estimated monthly payment: $4480. Recommended income: $150,000 per year. - Bothell, WA Rectory Value: $951,000. (Median House: $529,000)

Estimated monthly payment: $6051. Recommended income: $202,000 per year. - Edmonds, WA Rectory Value[2]: $1,600,000. (Median House: $541,000)

Estimated monthly payment: $10,281. Recommended income: $343,000 per year.

The average rectory value was $888,400 in a region where the average house is valued at $514,000 (or, 172% the price of a ‘median’ house). Only in one case was the rectory valued lower than the typical house, and in most cases they were considerably higher. One would have to be earning an annual salary at least $192,200 in an area where the median household income is $58,000, in order to live in these rectories – and most Church employees are not even making the state median income.

Extrapolating this trend to the national median house price, we could estimate that the national typical rectory is valued at about half a million dollars, meaning a mortgage or rent of $3000 a month for the lay employee wanting to buy or rent the same place. An additional $36,000 a year is well beyond the taxable extras indicated by the NACPA survey. The main reason for this is probably that many of the properties are already owned in full by parish or diocese, so the cash flow is calculated differently, but to my question: what would it take for the lay employee to live there, this is the more accurate measure of wealth differential.

Our priest is now not only $406,500 better off to begin with, but at an advantage of $36,000 per annum. On average. In a place like western Washington State (where my rectory examples are from), the annual disparity is nearly double.

Unemployment

These days, it is not unusual to be without work for some period of time, no matter how educated, skilled, or driven one is. Though Baby Boomers tend to think of these as irregular, it is an expected part of professional life for GenX and Millennials. About 1 in 5 workers are laid off every five years, in the twenty-first century, and 40% of workers under 40 have been unemployed for some significant amount of time in their short careers. I can only imagine this statistic is higher for those who have worked (or tried to work) for the Church.

When a priest is incompetent, or just not a good fit for a particular job or office, it is almost impossible to have him moved or fired. Even when he does, his livelihood is never in question.

Even when a lay minister is at the top of his or her game, an economic downturn will affect them far before the priest. Our exemplar lay minister not only has to worry that he could lose his job just because the new pastor does not like lay people or feels threatened by anyone with a theology degree besides himself, s/he has to worry about more than just a loss of respect or office, but something as simple as whether or not he can afford a place to live, health care, or the cost of moving to a new job. Lay ministers are not even entitled to state unemployment benefits, being employees of a religious institution. If he or she is out of work for a month or two, that means a significant loss of income and increase in stress, not vacation time.

How do we quantify this? Certainly, the psychological advantage of knowing you have virtually untouchable job security is priceless. Based on some (admittedly unscientific) survey of other lay ecclesial ministers, an average seems to be about one month of (unpaid, involuntary) unemployment for every three years of working for the Church. Based on the median annual pay and benefits of such ministers, that’s a little more than $4300 in lost income and benefits every three years, or about $1450 a year we can add to the priest’s income advantage, which now stands at $406,500 out of the blocks and $37,450 annually.

Blurred boundaries and clerical culture

Some years ago, I was at a conference once with several priests, and we decided to go out for a steak dinner at a nice downtown establishment. One of the priests (soon after, a bishop) reached for the bill, pulled out a credit card, and said, “Dinner’s on the parishioners of St. X’s tonight!”

Whether he meant the he was paying out of his own pocket for our dinner but realized his salary came from parish giving, or that he was using the parish credit card (and budget) was a little unclear, but it seemed like the latter.

Even the most well-intentioned priest is hard-pressed to clarify where his personal finances begin and the parish’s ends in every case, especially as he has essentially full control over the latter, what with most parish finance councils being merely ‘consultative’. For those who feel they are entitled to the benefices of their little fiefdom, it is only too easy to meet basic needs without even touching one’s official salary or stipend.

Sometimes it is a result simply of not knowing any other way. When I was a grad student, the then-chair of theology was a Benedictine monk. At the end of my first year, he called me in to inquire why I, as a scholarship student, was not getting straight A’s. When I mentioned the 25-30 hours I put in at work each week, he was perplexed: why was I working while in studies? I pointed out that my scholarship covered only tuition, and not university fees, housing, food, insurance, travel and transportation, books, computer, etc., he sat back and with a rather distracted look on his face said, “Oh… I forgot about all that.” Such is the advantage of the ‘wealthy’ – even in vows of poverty!

I cannot calculate the untaxed income of intentional or innocent blurring of boundaries between budgets, but we would be naïve if we did not realize that our current quasi-monastic compensation structure lends itself to confusion at best, and abuse at worst. Certainly, most priests are among the well-intentioned and conscientious in this regard. That does not mean we cannot improve.

Conclusions and Solutions

Fifteen years after ordination or the beginning of a career in ministry, our two Church ministers are sitting quite differently. Nearly $970,000 differently, in fact. Our priest started with $406,500 in education advantages, and enjoyed housing and security advantages at a rate of $37,450 per year.

In other words, in order for our lay ecclesial ministers to be living on par with our priest – their average salary should be about $96,000 per year (plus benefits) – nearly triple the current reality. (Calculated by dividing the education advantage over twenty years, and adding the annual advantage to the average annual pay).

Remember, this is not all cash in hand, or the kind of wealth you can take with you (I know most priests do not own the rectories in which they get to live, but then, most lay ministers are renting too.). Nor is this all of the same quality information – some is based on extensive national study, but where data is lacking, we have had to estimate a median goal by extrapolating from known reference points. Obviously, that means i will continue to update the figures up or down as more or better information presents itself.

But in terms of, “what would the lay minister’s salary have to be to enjoy the same ‘wealth’ as a priest” there is your answer. These are expenses the priest never personally had, that the lay minister did or would have to have had to live in the same houses, have the same education, etc.

So how can we make our compensation structure more just, more transparent, and more equitable?

The detailed information in the NACPA study helps, but it only address some of the problems. Accounted taxable income is only a portion of the income disparity, as we have seen. So what could we do differently?

Perhaps when a bishop or pastor hires a lay ecclesial minister, he should compensate them for the education they paid for that he now gets to take advantage of, to the same degree as what he would have paid for a priest in their situation? How does a $406,500 signing bonus sound? At the very least, compensate the individual as you would a fellow bishop when a priest from his diocese is excardinated from there to join yours.

On that note, all ministers should be incardinated, or registered, or something. It really makes no sense, ecclesiologically, to have any kind of ‘free-agent’ ministers in the Church, which is how our lay ministers are treated. All ministry is moderated by the bishop, and all ministers are, first of all, diocesan personnel, ‘extending the ministry of the bishop’. They should be organized, supported, and paid as such. (At the bare minimum, they should show up in every dioceses’ statistics on pastoral personnel!)

I am a big supporter of the idea that all of our ministry personnel – presbyters, deacons, and lay ecclesial ministers – should all follow the same compensation system and structure. Preferably, a straight salary. This clarifies the boundaries, makes real tracking of compensation easier, and clarifies comparable competencies.

Wherever the Church wants to remain in the real estate and housing business – though i am unsure if it should – these should be administered at the deanery level and set up as intentional Christian communities for ministers. Will have to write something else about this.

The same should be said for support and funding for formation and education. When the majority of parish ministers are lay ecclesial ministers (which has been the case for over a decade in the States), the majority of funding should be going to support their formation.

The same is true for advanced studies. Too often bishops seem to forget that their pool of human resources is wider than just the presbyterate. Raise up talent wherever it is found, and you will find dedicated ministers and coworkers for the Lord’s vineyard.

Years ago, I met a young woman who wanted to spend her life in service of the Church, and so was pursuing a degree in canon law. She had written dozens of bishops asking for some kind of support or sponsorship in exchange for a post-graduation commitment to work, and received only negative responses. Her classmates were all priests ten to twenty years her senior, most of whom had not chosen to study canon law, and all receiving salaries in addition to a full ride scholarship from the diocese.

When she and I caught up ten years later, half her class was no longer even in priestly ministry, and she was still plugging along, serving as best she could. Talk about potential return-on-investment! Hundreds of thousands wasted on priests who did not want to study canon law in the first place, a fraction of which would have yielded far better results with this one young lay woman. Imagine how many more are out there denied the opportunity to serve simply because not enough support is offered.

You never know what it is that will catch people’s attention. I hoped this post would provoke some thought, at least among friends and colleagues who read my now very occasional postings, but never thought this would be one to run viral. Read 4000 times here, shared 900 times on Facebook (!), quoted in America and prompting at least one blog in response, i have read and engaged many comments and am adding a follow up to those – many insightful – in a new post.

[1] Household median income is the standard measure of “average salary” in the U.S. census and demographic studies; it includes single-earner households such as our examples of a priest or a single lay ecclesial minister. The average per capita income for the same state was $30,000. (For the county in question, median household income is $68,000 and average per capita is $38,000.)

[2] This is the only one I had to make an estimate. Neighboring houses ranged from $800K to $1.5m, all of which were substantially smaller, on less property, and none of which featured an outdoor swimming pool… So I am, if anything, probably a bit conservative on the estimate.

Facebook’s no “Father” fascism (and other woes of our age)

There is a new kind of fortnight for freedom on Facebook campaign. For the last couple of weeks one of the most pressing issues facing the church has not been, according to my newsfeed: the martyrs created by ISIS, the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine, the plight of immigrants and refugees, or the staggering disparity between multibillionaires and the billions in poverty. Rather, we must raise up arms about a new (or newly enforced) policy on Facebook that people ought to be using their real names. Petitions are being signed, editorials written, and, naturally, Facebook pages have been created.

There is a new kind of fortnight for freedom on Facebook campaign. For the last couple of weeks one of the most pressing issues facing the church has not been, according to my newsfeed: the martyrs created by ISIS, the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine, the plight of immigrants and refugees, or the staggering disparity between multibillionaires and the billions in poverty. Rather, we must raise up arms about a new (or newly enforced) policy on Facebook that people ought to be using their real names. Petitions are being signed, editorials written, and, naturally, Facebook pages have been created.

Shocking, I know.

The thing is, though, there are already two solutions in place. Here is a radical idea: Before starting a virtual religious freedom riot, why not see if you can get what you want by using the tools already at hand?

The first options is the Public Figure Page. This is intended for people with a following. Celebrities and theologians and whatnot. Here I use the well-known Father Robert Barron as an example. He has two facebook pages:

- His personal page is Robert Barron. He has 84 friends. (Somehow, I still know he’s a priest).

- His public figure page is Father Robert Barron, with over 411,000 likes.

You can use titles for public figures, no problem.

The second option is the “Name with Title” option.

The second option is the “Name with Title” option.

(screenshot included)

- Go to your profile’s “About” tab,

- click on “Details about you”

- under “Other Names” click on “add nickname, birthname,…”

- on the drop down menu for name type select “Name with Title”

- Type in whatever you want: Deacon Tom, Father Dick, Bishop Harry, Pope Sixtus VI….

- Click “Save Changes”.

Now, as a Catholic Christian, I have no problem with this “real names” rule. Online integrity is part of “though shalt not lie” as far as we are concerned. No need for aliases, pseudonyms, or the “anonymous” setting behind which we can sling mud. No, all trolling must be done in our own name, as our online presence is an extension of ourselves. Recent remarks by both Pope Francis and Pope Benedict XVI, usually on World Communications Day, have underscored this idea.

However, some in the flock are not satisfied that they cannot present their title or style of address as if it is part of their name. This has primarily been a concern of priests and seminarians, some deacons and sisters. It is apparently some kind of anti-Catholic conspiracy, despite the fact that the policy applies to rabbis and imams and wiccan priestesses and pretty much everybody else as well.

Some clergy have taken to creating neologisms for their names, as Father Ralph becomes FrRalph and Deacon Bob becomes DeaconBob. Others have changes their profile pictures in protest (samples inserted).

As a child of the digital age, a postmodern son of the Church (at least by generation), I am not inclined to agree. (And, as far as I can tell, Catholic doctors, judges, and professors have not expressed similar outrage.)

As a child of the digital age, a postmodern son of the Church (at least by generation), I am not inclined to agree. (And, as far as I can tell, Catholic doctors, judges, and professors have not expressed similar outrage.)

If I see your occupation is physician, I know it is polite to address you as “Doctor”; if you teach at university, I know your style is “Professor”; if I see you are a priest or deacon, I know that “Father” is a customary style of address, and will likely choose to address you that way.

It is not your name, however. Your name is your name, and that should be sufficient. Your name was good enough for your Christian Initiation, it is certainly good enough for your ordination, to say nothing of your Facebook page.

It would be similarly pretentious, and inaccurate, to introduce yourself by saying “Hello, my name is Father Smith” or “My name is Doctor Jones”. NO: your name is Bob Smith or Tom Jones. Father, or Doctor, is not part of your name.

You could say, “Call me Father Smith” or “Call me Ishmael” if you want me to call you something other than just your name, but your name is your name. Be proud of it, and do not confuse it with your title.

“Simple is the new chic”

So says an octogenarian cardinal usually known in Rome for his sartorial splendor, when asked upon his recent appearance in a Trastevere trattoria in simple black clerical suit.

The tale is relayed by John Allen, the well-known vaticanist at dinner, from his own experience earlier this year, at the end of one of those typical Roman days where you get nothing done that you planned, but which turns out so much more interesting for it.

During the course of the day, which started with the Divine Liturgy at the Russicum (the Russian Catholic collegio), I have broken bread with a Byzantine-rite Jesuit, the organizer of an international Vatican conference, two archbishops, the aforementioned vaticanist, a papal dame, a worker-priest, journalists and students from five continents. Before yesterday I had not expected any of it.

Discussion ranged to include, (somewhat predictably):

- Pope Francis’ big interview;

- Cardinal Piacenza’s perceived demotion (officially a lateral move) from Congregation for Clergy to Major Penitentiary;

- Archbishop Gus DiNoia’s unclear mandate as adjunct secretary at CDF (he had been the last ditch effort to save the talks with SSPX, after even our most traditionalist-friendly prelates assigned to the dialogue team found the task untenable);

- the situation in Egypt, including an assessment that the military coup has popular support and will let democracy happen, if a party can be found that wont prove nepotistic or despotic;

- expectation that the canonization of popes John XXIII and John Paul II will indeed be on Divine Mercy Sunday (27 April);

- another impending financial scandal that will make the Vatican bank issues look like small potatoes;

- the fears that Francis, who reminds many of John Paul I, will be the target of an assassination plot;

- one world-traveled cleric claiming that his experience of worship at Caravita last week was one of the best he’s experienced, ever, anywhere (and that Fr. Gerry’s preaching was phenomenal);

- the removal of two bishops this week for sex abuse of children (in Dominican Republic and Peru);

- the positive effects of diocesan-wide petitions against their bishops (in both Germany and Brazil);

- rumors that Pope Francis is considering strict , non-renewable, 5-year term limits for all curial posts;

- German elections, Angela Merkel, and the evening’s Roma-Lazio game;

- and whether men appreciate women who are willing to ask men out, or if they find it unappealing (2:1 in favor of women taking the initiative, for the record).

OK, the last one may not have come up with the clerical company, but it did come up during the day!

One overarching theme was that everyone I talked to, in every different setting, was positive about Pope Francis, but unsure, still, about how much hope to have.

Part of that relates to the concern exemplified by the “simple is chic” cardinal. If that’s all it is – knowing which way the wind is blowing – I think I would rather trust a priest who sticks to his French cuffs or a prelate preening in his watered silk, if that is what they really think is appropriate, rather than those who are simply dressing up or down according to the boss’ style. Because then none of the change is permanent, and it will shift with the sands. I might disagree with the capa magnas and the little fiefdoms, but I have much greater respect for the prelate princeling or the lord of the rectory manor who admits what he is than the one who plays the game just to look the part, whichever way it goes.

Now, if the bishop of Rome really wants to curtail clericalism, he might just announce that anyone working at any level in the curia or the diplomatic corps will be ordained only to the diaconate, in accordance with their original vocation, and neither to the presbyterate nor to titular dioceses long-since buried under the Sahara. Wouldn’t that be interesting?

Married Priests: Optional Celibacy among Eastern Catholics – Past and Present

Report on the Chrysostom Seminar at the Domus Australia, Rome

November 2012

Did you know that there are now more married Roman Catholic priests in the U.S. than Eastern Catholic priests?

I do not actually remember a time when I did not know that there were married Catholic presbyters, so it has always been amusing to encounter people who find this a scandal in some way. The real scandal is that Catholic Churches with a right (and a rite!) to ordain married men are not allowed to do so, basically because of 19th and 20th century anti-immigrant sentiment, in the U.S.

That was not a main theme of the conference this morning, but it was certainly an interesting fact that was new to me.

Of the varied and lively discussion, probably the main take-away theme was this: The Gospel does not coerce, but offers conversion.

In other words, conversion is a response of the heart, whereas coercion is an exercise of power. Any relationship of supposedly sister churches, say, of Rome and of Constantinople – or of New York and Parma, for that matter – which is experienced as a relationship of coercion, becomes a church-dividing issue. This came up repeatedly regarding the imposition of a Latin discipline – mandatory celibacy for diocesan presbyterate – on non-Latin churches.

Speakers for the day included:

- Archpriest Lawrence Cross, Archpriest, Centre for Early Christian Studies, Australian Catholic University

- Rev. Prof. Basilio Petrà, Facoltà Teologica dell’Italia Centrale (Firenze)

- Rev. Thomas Loya, Tabor Life Institute, Chicago:

- Protopresbyter James Dutko, Emeritus Dean of the Orthodox Seminary of Christ the Savior, PA

- Archpriest Peter Galazda, Sheptytsky Institute, Saint Paul University, Ottawa

Archpriest Dr. Lawrence Cross spoke on “Married Clergy: At the Heart of Tradition.” Father Cross opened by stating for the record that the conference here was not a critique on the Latin practice, internally, but a protest against what he described as ‘bullying’ in some parts of the Latin Church against Eastern sister churches in communion with Rome: namely, the requirements in some places (such as the U.S.) that Eastern Catholic churches not allow married clergy because of pressure from the Latin (Roman) Catholic bishops.

Both married and celibate clergy belong to the deep tradition of the church. Though some try to point to the origins of mandatory celibacy as far back as the Council of Trullo in Spain, it is really from the 11th century Gregorian reforms – based on monasticism and coincident with a resurgence of manichaeism in the Church.

One of the results of this, much later, is the novelty, he says, of speaking of an ontological change in ordination, or an ontological configuration to Christ, as in Pastores Dabo Vobis 20, which sees married priesthood as secondary. One US Cardinal, he did not name, has referred to the ontological change of priesthood as analogous to the Incarnation or transubstantiation. The problem with the analogy is that the humanity of Christ is unchanged! Trying to assert an essential link between priesthood and celibacy, something which has been relatively recent in its effort, is problematic.

Indeed, there is no celibacy per se, in the Eastern tradition, just married or monastic life. Both require community, and vows to commit one to that community. The Code of Canons of the Eastern Church 374-5 highlights to mutual blessing that marriage and ordination offer to each other. He wonder why Pope John Paul II, who seemed to have such a high respect for the “primordial sacrament” did not see fit to apply it to the presbyterate.

Professor Basilio Petrà of the Theological Faculty of Central Italy (in Firenze), spoke on the topic of “Married Priests: A Divine Vocation.” Two immediate thoughts he shared were that the Catholic Church has always, officially at least, affirmed married priesthood, and to consider that vocation is always a call of the community and not of the individual. Marriage and priesthood are two separate callings, but both sacraments and therefore complementary not competitive.

Fr. Petrà drew attention to the recent apostolic exhortation, Ecclesia in Medio Oriente, which included this paragraph:

48. Priestly celibacy is a priceless gift of God to his Church, one which ought to be received with appreciation in East and West alike, for it represents an ever timely prophetic sign. Mention must also be made of the ministry of married priests, who are an ancient part of the Eastern tradition. I would like to encourage those priests who, along with their families, are called to holiness in the faithful exercise of their ministry and in sometimes difficult living conditions. To all I repeat that the excellence of your priestly life will doubtless raise up new vocations which you are called to cultivate.

While he emphasized the positive nature of the bishop of Rome including the married priesthood as a respected and ancient tradition in the east, it is interesting to note that while celibacy is a priceless gift of God” which “ought to be received in East and West alike,” married priesthood is not categorized as a gift of god but “a part of the tradition” and only in “the East.”

Father Thomas Loya of the Tabor Life Institute in Chicago, and a regular part of EWTN programming, presented on the topic, “Celibacy and the Married Priesthood: Rediscovering the Spousal Mystery.” Married priesthood witnesses to the Catholic tradition of a life that is ‘both-and’ rather than ‘either-or.’ We need a more integrated approach to monasticism and marriage, and relocating celibacy in its proper monastic context. But the continued practice of requiring eastern Catholic churches to defer to the Latin church hierarchy with respect to married clergy is to act as though the Latin Church is the real Catholic Church and the eastern churches are add-ons – fodder for accusations of uniatism if ever there was.

One of the clear problems of this was that when, in 1929, celibacy was imposed upon eastern churches in the US and elsewhere, married priesthood was part of the strength of these churches. Since then vocations have disappeared, evangelization has all but ceased, and the general life of the churches has withered. After “kicking this pillar of ecclesial life out from under the churches” it offered nothing to hold them up in its place, and the Church is still suffering.

Can you imagine a better seedbed for presbyteral vocations than a presbyteral family? What better way for a woman to know what it would be like to marry a priest than to be the daughter of a priest?

Married priesthood is part of the structure of the Church, but celibacy always belonged to the monasteries. Without a monastic connection, a celibate priest is in a dangerous situation, lacking the vowed relationship of either marriage or monastic life to balance the call to work. Every celibate must be connected to a monastery in some way.

Just as a celibate monastic must be a good husband to the church and community, so too must a married couple be good monastics. The relationship of monasticism and marriage ought to be two sides of the same coin and mutually enriching. The call to service in ordained ministry comes from these two relationships to serve. This would be a sign of an integrated and healthy church.

Protopresbyter James Dutko is retired academic dean and rector of the Orthodox Seminary of Christ the Savior in Johnstown, PA. His topic was “Mandatory Celibacy among Eastern Catholics: A Church-Dividing Issue.” Father Dutko was the only Orthodox presenter on the panel (and the only one without a beard, incidentally…) The bottom line? As long as the Latin Church (that is the Roman Catholic Church) imposes its particular practice on other Churches even within its own communion, there will be no ecumenical unity. Stop the Latinization, and the Eastern Orthodox may be more inclined to restore full communion.

Almost Reverend

I originally posted this a couple of years ago on a different blog. I came accross it recently, and given where i am now (that is, Rome), it still seems funny, and i hope you can appreciate the humor. [Disclaimer: No clerics were harmed in the making of this post.]

**Original Post: August 15, 2008**

At an ecumenical meeting not long ago, i found myself again trying to explain lay ecclesial ministry to a Lutheran pastor. While many non-Catholics (and even some Catholics) often think the only ministers in the Catholic Church are priests, at least this one had been ecumenically involved long enough to know different. He just was not sure how to address me.

“As a member of the Board,” he said, “you deserve to be addressed with appropriate formality in correspondence, and appropriate respect during meetings. So, what do we call you?”

I told him the name given me at my birth and baptism was Andrew, and that was fine – or A.J., as I have been known since birth: “No adornments necessary.”

Pressed, however, I shared how evangelical Christians i meet with invariably address me as “Pastor Boyd”, since anyone who does professional pastoral ministry is, ipso facto, a pastor, and therefore called “pastor”. I noted how, every time i got something from Hilel or the local synagogue, it was addressed to “Rev. Boyd”, because, again, the logic is, clergy are professional ministers, and I am a professional minister, so i must be clergy. Even when filling out legal forms, i often have to select “clergy” as my occupation, because for the uninitiated, clergy is defined by Webster, and not the Codex Iuris Canonicis, as “a group of church officials doing official church ministry”.

After all this, i was informed it just was not acceptable. We had to find something appropriate to my position as not-ordained but vocational, “professional” minister of the Church while respecting the internal distinction between clerical and lay ministers. So we began an exploration.

“Virtually Reverend”, “Not-Quite-Reverend”, and “Sort-of-Reverend” were all suggested before we alighted on “The Almost Reverend”.

After my colleague observed that a personal style was needed, too, I remembered a line from a great book and movie about a pope, Saving Grace, and we decided the only possible ecclesiastical style for someone of such standing as myself was “Your Mediocreness…”

Therefore I can now fit in at the next clerical cocktail party as “His Mediocreness, The Almost Reverend A. J. Boyd”.

I am thinking of petitioning the Pontifical Council for the Laity for making this a universal norm…

The Challenge of Priesthood

This should not be the topic of my first blog touching on the Year of the Priest. Maybe it should a story of vocation, or a theological reflection on the priesthood of Christ and his church. Perhaps an ecclesiological exposition of the ministerial priesthood of the bishop, presbyter, and deacon, with ecumenical emphasis. That is the price of procrastination, however. Those will come in time.

I came across both of these articles yesterday evening, and it was too powerful to avoid.

The first is from my diocesan newspaper, the Catholic Northwest Progress, in part of a series highlighting the presbyterate of the archdiocese in honor of the Year of the Priest; they provide brief profiles of five pastors each issue. This week’s issue includes five whom I know personally. Two were in seminary formation with me; two have worked with me as collaborators for the pastoral leadership of a parish; I have had several conversations with each, and have known most of them since I was 17 or 18.

Given that familiarity, I was mostly skimming the profiles. What priest does not think the greatest joy of being a priest is celebrating the sacraments, anyway? (Well, OK, there was one). I almost missed “the greatest challenge as a priest” on my first read, but that is the most telling part. Most of us who are or have been in pastoral ministry find that time-management and administration is an omnipresent challenge, and legitimately so. Yet, one response truly stands out, and calls us to remember what ministry, and the presbyterate, is really about.

To then turn to the next article only confirmed that read. Archbishop Diarmuid Martin of Dublin addressed this week’s release of the national investigation of the sexual abuse of children and its systematic cover-up by the Catholic hierarchy in Ireland. The report itself reads much like the reports in the States over the last ten years. What reads differently is the response of the archbishop himself, which should be read in full and is available here:

Three times, the archbishop repeats that “No words of apology will ever be sufficient.”

He acknowledges not only the profoundly sinful nature of the acts of abuse by priests, but also the abject failure of the bishops and religious superiors to act for good:

“One of the most heartbreaking aspects of the Report is that while Church leaders – Bishops and religious superiors – failed, almost every parent who came to the diocese to report abuse clearly understood the awfulness of what has involved. Almost exclusively their primary motivation was to try to ensure that what happened to their child, or in some case to themselves, did not happen to other children.”

He does not equivocate, blame the media, secular society or anti-Catholic bias; he does not claim that they ‘did not understand’ the nature of the pedophile and the ephebophile thirty years ago, or that they needed a ‘learning curve’ to adequetely deal with these problems. He makes no excuse for the culture of clericalism and institutionalism that allowed and encouraged the perpetuation of grave sin:

“Efforts made to “protect the Church” and to “avoid scandal” have had the ironic result of bringing this horrendous scandal on the Church today.”

In his interview he refers to the people making these excuses as a ‘caste’, a group who thought they could do anything and get away with it – which makes the crimes all the more horrendous because they were perpetuated by those who serve in the name of Jesus Christ.

There may be a long way to go before all remnants of that caste-mentality are eradicated from the Church, but our prayers and dedicated efforts to that end must never cease. Structures of sin have no place in the Body of Christ.

It reminds me of a parishioner whose daily intercession at Mass was for the “holiness of our priests” – simultaneously a prayer of gratitude for the many holy men who serve the Church, and a plea for the conversion of the rest.

Amen, indeed.

Shopping for Roman collars

Everyone in Rome has a uniform and a title; and that’s if you are a nobody. If you are important, you also have a stamp, a wax seal, and most likely a signet ring. Perhaps this is why electronic means of communicating, providing identification, registering for classes, paying bills, and the like are so difficult and considered downright foreign here. I’ve gone through i don’t know how many hard-copy pictures of myself, and every correspondence to everyone needs to be an original letter, signed, co-signed and countersigned, then stamped in duplicate or triplicate.

Norbertine Habit

But back to the uniforms: One of the many blessings of being in Rome is seeing the life of the church in all its profound diversity. You cannot maintain the illusion of a monolithic Catholicism very long in this capital of the church. I’ve seen habits for orders i had heard of but never met: Norbertines, for example, dress in a white simar and fascia looking almost identical to the pope. Then there are those i did not even know existed: the Teutonic knights, apparently, are back as a diocesan order, and looking very medieval.

Even most of the lay people around here are in ecclesiastical garb, particularly seminarians and lay religious, even during classes. So, naturally, I am on a mission to discover the appropriate ecclesiastical garb for a lay ecclesial minister. After all, if a student candidate for ministry gets a uniform, so too should someone already in sacred ministry, no?

(The current favored title is “Almost Reverend…”, or “Your Mediocreness”, and the garb is a white or black dress shirt with banded collar, though I am open to suggestions. But, I digress.)

Archbishop Wilton D. Gregory

Allora… I decided to peruse the ecclesiastical shopping district near the Pantheon with Stian, an Anglican seminarian and friend of mine who shares that you can get four clerical shirts in Rome for the price of one in Norway.

We picked up a couple new friends on the way, Matthew, from Australia, and Cosima, from Germany. While Stian was being fitted for his clericals, the rest of us were perusing the mitres, zucchetti, and birettas that seemed to be available over the counter.

Did you know that with an ecclesiastical doctorate one is entitled to wear a biretta with the appropriate color trimming? For theology, it’s scarlet; canon law is green, etc.

As we were about to leave in search of a pizzeria and gellateria, America’s lone representative to the Synod for Africa, Archbishop Wilton Gregory of Atlanta, walked in for some shopping of his own. He was kind enough to stop for a brief chat about the Synod, and exchange a warm greeting before we moved on for pizza and gelato. At least now we know we were in the right shop!