Home » Posts tagged 'clergy'

Tag Archives: clergy

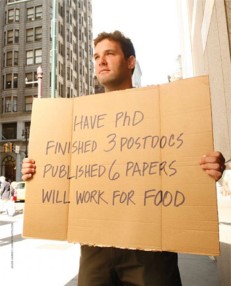

If I wanted to be wealthy, I should have been a priest

What is missing in the 2017 National Diocesan Survey on Salaries and Benefits for Priests and Lay Personnel? (Commissioned by the National Association for Church Personnel Administrators [NACPA] and the National Federation of Priests’ Councils [NFPC], it was carried out by the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate [CARA]). The overview seems both modest and comparable to the typical lay ecclesial minister’s income:

If I were a priest, I could probably afford the $795 that NACPA is charging to download a copy of their full study, and find out in closer detail. But as a lifetime lay employee of the Church, I have to take it as a given that the good people at NACPA (mostly lay pastoral administrators) have crunched their numbers accurately and the $45,593 is in fact the median taxable income of U.S. priests. A table of contents is publicly available which indicates what they did (and did not) consider.

What about the untaxable income? What about the things that are hard to quantify but observably make a difference? Or easy to quantify but simply taken for granted? What about the expenses that the lay counterpart has that the priest does not? A penny saved is a penny earned, after all.

A pastor I know complained – often and loudly – that he was paying the lay pastoral staff at his new assignment far too much (A little less than $50,000 per year, less than the state’s average income[1]). To his credit, the pastoral council president, who had been involved in the hiring process with the previous pastor, usually replied that the staff were paid about 1/3 of what they were worth in the private sector, and the young priest should be a little more appreciative.

Fr. Scrooge’s attitude got me thinking about the apparent disparity between compensation for equally qualified people with a vocation to ecclesial ministry.

Look at two people of reasonably comparable demographic – single, no children, with undergraduate and graduate degrees in theology/divinity, committed to a life of ministry in the Church – and consider them in a similar parish, similar ministry, with similar qualifications, experience, and responsibility. One is a priest, the other a lay ecclesial minister.

There is no question the priest in such a scenario is “wealthier” – enjoying a higher standard of living, a nicer house, with greater stability, and less stress about making ends meet. So how does this observable reality reconcile with the apparently low income that priests have, according to the NACPA study? Something is missing.

Considering a few major areas of disparity, we can easily track how those pennies add up, taxable or otherwise.

Education

Source: Mundelein Seminary

In the U.S., the standard education and formation program for a priest is to have a four-year Bachelor’s degree (in anything, really, but with a year’s worth of philosophy and theology at the undergrad level before graduate seminary), and a three-year Master of Divinity or equivalent, plus a pastoral internship year. Most lay ecclesial ministers have something similar, if, of necessity, in a greater variety of configurations.

In one diocese I am familiar with, the entire cost of seminary is covered, at least from pre-theology onward, plus a variable stipend for travel and spending. For college seminarians, the students are accountable for half their cost (which could be covered by scholarships they earned from the university, for example).

The average cost of tuition and fees at Catholic colleges and universities in the U.S. in 2016-2017 was about $31,500, with the highest ones being around $52,000 (Source: ACCU). So let us say the diocese i mentioned is typical, and pays for two years of the undergraduate and all three years of the graduate costs for formation: middle-of the road estimate of $157,500 per seminarian.

An additional spending stipend can range from $2000-$6500 per year depending on where they are in studies. Let us say $4000 a year for ease of calculation. An additional $20,000 brings the educational investment up to $177,500. It would be interesting to see what the actual numbers on this spending are.

The candidate for lay ministry, on the other hand, has to work or take out loans, though in some places some assistance is available. Forty years ago, one could work full time at a minimum wage job in the summer to pay for a year of tuition at a respectable state school, but that has not been true since the 1980s. Despite savings, work-study, scholarships and grants, and, if fortunate, parent contributions, the average graduate leaves with $38,000 in student loan debt after a Bachelors, and about $58,000 all told if they have also a Masters from a private institution, which has to be the case if you have a degree in theology. (Source: Newamerica.org study, Ticas.org). The interest on that, at the standard federal rate of 6% over the life of the loan (twenty years) will add another $19,000 to the total.

So far, in terms of pennies saved and earned, the priest is $196,500 ahead, and ministry has not even begun.

But we are not done: the best and brightest are often called to graduate studies, say, a license in canon law or a doctorate in theology.

Another three years of graduate school for a JCL (or five, at minimum, for a doctorate). In Rome, where tuition is cheap but living is costly and jobs are hard to find, it is easy to contrast the stability and support given to clergy with the complete chaos experienced by most laity – who, nevertheless, sacrifice more and more in answer to a vocation to serve the Church.

About $25,000 a year, (choosing the cheaper options of a canon law degree in Rome), and there’s another $75,000 where our priest has uncounted ‘income’.

He is now $271,500 better-off than the lay counterpart …and we are not even counting the little extras Knights of Columbus ‘pennies for heaven’ drives or Serra club gifts.

Note, too, that the priest-grad student continues to draw a salary/stipend, plus other benefits like housing and food stipends, while in studies; the lay minister has to give all this up to pursue studies. According to the study, that means adding another $45,000 per year to the priest’s advantage.

So, make that $406,500 ahead of the lay minister with the same education.

Housing

St. George Parish Rectory, Worcester, MA.

Housing was calculated in the NACPA study, either (or both?) in terms of taxable cash allowances and housing provided, but it is hard to reconcile the low-ball numbers given with the observable reality: Priests living alone in houses that are considerably larger and/or nicer than what their lay counterpart could ever afford to live in. How is this possible?

Simply ask the question: What is the value of the house (rectory) and what would it take to live there?

You can either look at the value of the rectory and estimate the salary required to afford such a place; or you can look at the salary earned and look at how much house someone with that income can afford, and how it compares.

Based on the 2012 CARA survey (being unable to see the 2017 median salary as it is behind a paywall), the median annual salary in 2010 was $34,200. That’s about $38,351 in 2017, factoring for inflation. Assuming no other debts (ha!), that means one could afford a house valued at about $185,000, considerably less than the median price.

The median house value is about $300,000 in the U.S., based on sales prices over the last year (Source: National Association of Realtors). To afford this, one would have to be making about $65,000 a year, at least, and paying $1800 a month mortgage or rent.

But is the typical rectory more or less expensive?

As a point of reference from which to extrapolate, I checked on the value of the rectories in the five parishes where I have lived and worked in the last twenty years. (Source: Zillow). I then compared their value to the median house value in the same cities or regions.

- Everett, WA Rectory Value: $550,000. (Median House: $330,000)

Estimated monthly payment: $3560. Recommended income: $120,000 per year. - Woodinville, WA Rectory Value: $641,000. (Median House $755,000)

Estimated monthly payment: $4366. Recommended income: $146,000 per year. - Bellingham, WA Rectory Value: $700,000. (me Median House: $415,000)

Estimated monthly payment: $4480. Recommended income: $150,000 per year. - Bothell, WA Rectory Value: $951,000. (Median House: $529,000)

Estimated monthly payment: $6051. Recommended income: $202,000 per year. - Edmonds, WA Rectory Value[2]: $1,600,000. (Median House: $541,000)

Estimated monthly payment: $10,281. Recommended income: $343,000 per year.

The average rectory value was $888,400 in a region where the average house is valued at $514,000 (or, 172% the price of a ‘median’ house). Only in one case was the rectory valued lower than the typical house, and in most cases they were considerably higher. One would have to be earning an annual salary at least $192,200 in an area where the median household income is $58,000, in order to live in these rectories – and most Church employees are not even making the state median income.

Extrapolating this trend to the national median house price, we could estimate that the national typical rectory is valued at about half a million dollars, meaning a mortgage or rent of $3000 a month for the lay employee wanting to buy or rent the same place. An additional $36,000 a year is well beyond the taxable extras indicated by the NACPA survey. The main reason for this is probably that many of the properties are already owned in full by parish or diocese, so the cash flow is calculated differently, but to my question: what would it take for the lay employee to live there, this is the more accurate measure of wealth differential.

Our priest is now not only $406,500 better off to begin with, but at an advantage of $36,000 per annum. On average. In a place like western Washington State (where my rectory examples are from), the annual disparity is nearly double.

Unemployment

These days, it is not unusual to be without work for some period of time, no matter how educated, skilled, or driven one is. Though Baby Boomers tend to think of these as irregular, it is an expected part of professional life for GenX and Millennials. About 1 in 5 workers are laid off every five years, in the twenty-first century, and 40% of workers under 40 have been unemployed for some significant amount of time in their short careers. I can only imagine this statistic is higher for those who have worked (or tried to work) for the Church.

When a priest is incompetent, or just not a good fit for a particular job or office, it is almost impossible to have him moved or fired. Even when he does, his livelihood is never in question.

Even when a lay minister is at the top of his or her game, an economic downturn will affect them far before the priest. Our exemplar lay minister not only has to worry that he could lose his job just because the new pastor does not like lay people or feels threatened by anyone with a theology degree besides himself, s/he has to worry about more than just a loss of respect or office, but something as simple as whether or not he can afford a place to live, health care, or the cost of moving to a new job. Lay ministers are not even entitled to state unemployment benefits, being employees of a religious institution. If he or she is out of work for a month or two, that means a significant loss of income and increase in stress, not vacation time.

How do we quantify this? Certainly, the psychological advantage of knowing you have virtually untouchable job security is priceless. Based on some (admittedly unscientific) survey of other lay ecclesial ministers, an average seems to be about one month of (unpaid, involuntary) unemployment for every three years of working for the Church. Based on the median annual pay and benefits of such ministers, that’s a little more than $4300 in lost income and benefits every three years, or about $1450 a year we can add to the priest’s income advantage, which now stands at $406,500 out of the blocks and $37,450 annually.

Blurred boundaries and clerical culture

Some years ago, I was at a conference once with several priests, and we decided to go out for a steak dinner at a nice downtown establishment. One of the priests (soon after, a bishop) reached for the bill, pulled out a credit card, and said, “Dinner’s on the parishioners of St. X’s tonight!”

Whether he meant the he was paying out of his own pocket for our dinner but realized his salary came from parish giving, or that he was using the parish credit card (and budget) was a little unclear, but it seemed like the latter.

Even the most well-intentioned priest is hard-pressed to clarify where his personal finances begin and the parish’s ends in every case, especially as he has essentially full control over the latter, what with most parish finance councils being merely ‘consultative’. For those who feel they are entitled to the benefices of their little fiefdom, it is only too easy to meet basic needs without even touching one’s official salary or stipend.

Sometimes it is a result simply of not knowing any other way. When I was a grad student, the then-chair of theology was a Benedictine monk. At the end of my first year, he called me in to inquire why I, as a scholarship student, was not getting straight A’s. When I mentioned the 25-30 hours I put in at work each week, he was perplexed: why was I working while in studies? I pointed out that my scholarship covered only tuition, and not university fees, housing, food, insurance, travel and transportation, books, computer, etc., he sat back and with a rather distracted look on his face said, “Oh… I forgot about all that.” Such is the advantage of the ‘wealthy’ – even in vows of poverty!

I cannot calculate the untaxed income of intentional or innocent blurring of boundaries between budgets, but we would be naïve if we did not realize that our current quasi-monastic compensation structure lends itself to confusion at best, and abuse at worst. Certainly, most priests are among the well-intentioned and conscientious in this regard. That does not mean we cannot improve.

Conclusions and Solutions

Fifteen years after ordination or the beginning of a career in ministry, our two Church ministers are sitting quite differently. Nearly $970,000 differently, in fact. Our priest started with $406,500 in education advantages, and enjoyed housing and security advantages at a rate of $37,450 per year.

In other words, in order for our lay ecclesial ministers to be living on par with our priest – their average salary should be about $96,000 per year (plus benefits) – nearly triple the current reality. (Calculated by dividing the education advantage over twenty years, and adding the annual advantage to the average annual pay).

Remember, this is not all cash in hand, or the kind of wealth you can take with you (I know most priests do not own the rectories in which they get to live, but then, most lay ministers are renting too.). Nor is this all of the same quality information – some is based on extensive national study, but where data is lacking, we have had to estimate a median goal by extrapolating from known reference points. Obviously, that means i will continue to update the figures up or down as more or better information presents itself.

But in terms of, “what would the lay minister’s salary have to be to enjoy the same ‘wealth’ as a priest” there is your answer. These are expenses the priest never personally had, that the lay minister did or would have to have had to live in the same houses, have the same education, etc.

So how can we make our compensation structure more just, more transparent, and more equitable?

The detailed information in the NACPA study helps, but it only address some of the problems. Accounted taxable income is only a portion of the income disparity, as we have seen. So what could we do differently?

Perhaps when a bishop or pastor hires a lay ecclesial minister, he should compensate them for the education they paid for that he now gets to take advantage of, to the same degree as what he would have paid for a priest in their situation? How does a $406,500 signing bonus sound? At the very least, compensate the individual as you would a fellow bishop when a priest from his diocese is excardinated from there to join yours.

On that note, all ministers should be incardinated, or registered, or something. It really makes no sense, ecclesiologically, to have any kind of ‘free-agent’ ministers in the Church, which is how our lay ministers are treated. All ministry is moderated by the bishop, and all ministers are, first of all, diocesan personnel, ‘extending the ministry of the bishop’. They should be organized, supported, and paid as such. (At the bare minimum, they should show up in every dioceses’ statistics on pastoral personnel!)

I am a big supporter of the idea that all of our ministry personnel – presbyters, deacons, and lay ecclesial ministers – should all follow the same compensation system and structure. Preferably, a straight salary. This clarifies the boundaries, makes real tracking of compensation easier, and clarifies comparable competencies.

Wherever the Church wants to remain in the real estate and housing business – though i am unsure if it should – these should be administered at the deanery level and set up as intentional Christian communities for ministers. Will have to write something else about this.

The same should be said for support and funding for formation and education. When the majority of parish ministers are lay ecclesial ministers (which has been the case for over a decade in the States), the majority of funding should be going to support their formation.

The same is true for advanced studies. Too often bishops seem to forget that their pool of human resources is wider than just the presbyterate. Raise up talent wherever it is found, and you will find dedicated ministers and coworkers for the Lord’s vineyard.

Years ago, I met a young woman who wanted to spend her life in service of the Church, and so was pursuing a degree in canon law. She had written dozens of bishops asking for some kind of support or sponsorship in exchange for a post-graduation commitment to work, and received only negative responses. Her classmates were all priests ten to twenty years her senior, most of whom had not chosen to study canon law, and all receiving salaries in addition to a full ride scholarship from the diocese.

When she and I caught up ten years later, half her class was no longer even in priestly ministry, and she was still plugging along, serving as best she could. Talk about potential return-on-investment! Hundreds of thousands wasted on priests who did not want to study canon law in the first place, a fraction of which would have yielded far better results with this one young lay woman. Imagine how many more are out there denied the opportunity to serve simply because not enough support is offered.

You never know what it is that will catch people’s attention. I hoped this post would provoke some thought, at least among friends and colleagues who read my now very occasional postings, but never thought this would be one to run viral. Read 4000 times here, shared 900 times on Facebook (!), quoted in America and prompting at least one blog in response, i have read and engaged many comments and am adding a follow up to those – many insightful – in a new post.

[1] Household median income is the standard measure of “average salary” in the U.S. census and demographic studies; it includes single-earner households such as our examples of a priest or a single lay ecclesial minister. The average per capita income for the same state was $30,000. (For the county in question, median household income is $68,000 and average per capita is $38,000.)

[2] This is the only one I had to make an estimate. Neighboring houses ranged from $800K to $1.5m, all of which were substantially smaller, on less property, and none of which featured an outdoor swimming pool… So I am, if anything, probably a bit conservative on the estimate.

Reforming the Roman Curia: Next Steps

This weekend, word started getting around that the much anticipated reforms of the Roman Curia were finally ready for delivery – at least a number of them.

Pope Francis met with the dicastery heads this morning to give them a preview of changes, though no official word yet on what they all will be.

What has been announced is that there is a new prefect of the Congregation for Divine Worship, which has been vacant since Cardinal Canizares Llovera was appointed as Archbishop of Valencia at the end of August. The new top liturgist of the Roman curia is Cardinal Robert Sarah of Guinea. Cardinal Sarah has been working in the Curia since 2001, first as Secretary of the Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples, and since 2010 as President of the Pontifical Council “Cor Unum”. The new prefect, like most of his predecessors, has no formal education in Liturgy.

The rest is a bit of informed speculation, and nothing is ever official until it is announced:

Among the long awaited and predicted reforms to the curia will likely be the establishment of a Congregation for the Laity – raising the dicastery dealing with 99.9% of the Church’s population to the same level as the two (Bishops and Clergy) that deal with the other 0.1%. The new Congregation would have, it seems, five sections: Marriage and Families; Women; Youth; Associations and Movements; and one other. Too much to hope it would be for Lay Ecclesial Ministry? The current Council has a section on sport, so perhaps that would be maintained, but I suspect not.

No one would be terribly surprised to see the new prefect of such a congregation turn out to be Cardinal Oscar Andrés Rodriguez Maradiaga of Honduras, since he suggested the move publicly last year. What would be a true sign of reform would be to appoint a lay person or couple with degrees and work experience in lay spirituality, lay ministry, or something related. Then make the first lay cardinal we have seen in a century and a half.[1]

The new congregation would certainly combine and replace the Councils for Laity and for Family, but could possibly also incorporate New Evangelization or Culture, which are directly related to the apostolate of the laity in the secular world.

If you read Evangelii Gaudium, though, it is clear that Pope Francis sees the “new Evangelization” as an aspect simply of Evangelization proper, and I would be less surprised to see this Council incorporated into the Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples. Culture would be appropriately aggregated to Laity.

The other big combination long anticipated would be a Congregation for Peace and Justice – or something similarly named. It would combine the Councils of Peace and Justice, Cor Unum, Health Care Workers, and the Pastoral Care of Migrants and Itinerant Peoples, and possibly the Academy for Life. It would have sections corresponding to these priorities: Life; Migrants; Health Care; Charity; and Peace and Justice in the World. Presumably, Cardinal Peter Turkson of Ghana would continue from the current homonymous council as the prefect of the new Congregation.

Finally, a revamp of the Vatican Communications apparatus has been underway for a couple of years, and we could expect to see something formal announced much like the Secretariat for the Economy. Perhaps a Congregation for Communications, or at least a stronger Council, with direct responsibility all communications in the Vatican: L’Osservatore Romano, Vatican Radio, CTV, the websites, various social media, the publishing house, etc.

Now, a couple of ideas that would be welcome, but are not expected:

The combination of the Congregations for Bishops and Clergy – have a single congregation with three or four sections: Bishops, Presbyters, Deacons, and Other Ministers/Lay Ecclesial Ministy. This would be especially possible if the responsibility for electing bishops – only in the modern era reserved to the pope – could be carefully restored to the local churches in most cases.

The creation of a Congregation for Dialogue, replacing the Councils for Promoting Christian Unity, Interreligious Dialogue, and the Commission for Religious Relations with the Jews. It would accordingly have several sections: Western Christians; Eastern Christians; Jews; Other Religions. Perhaps the whole Courtyard of the Gentiles effort could be folded into this as well.

Alternatively, leaving Ecumenism and Interreligious Dialogue in separate dicasteries but with more influence, like requiring every document coming out of the CDF and other congregations to be vetted before publication, to make sure they incorporate ecumenical agreements and principles as a sign of reception.

Formalization of the separation out from the Secretariat of State for responsibilities relating to moderating the curia. The Secretariat should be dealing with diplomatic issues. The rest could be reorganized in a number of different ways.

Streamlining of the judicial dicasteries, including removing the judicial aspects out from CDF and into a stand-alone tribunal. Granted, it is thanks to then-Cardinal Ratzinger and the CDF that any movement on abuser priests happened, but it is still anomalous to have. (Still need to work out what this would look like though).

A consistory which creates no new Italian cardinals – lets get the numbers down to a reasonable amount. Like five. If there are any (North) Americans, they would be the likes of Bishop Gerald Kicanas from Tucson, Archbishop Joe Tobin of Indianapolis, or Archbishop Peter Sartain of Seattle – but nobody else from east of the Mississippi. Maybe a bishop from Wyoming or Alaska, the real “peripheries” of American Catholicism. At least five Brazilians and another Filippino. Maybe an Iranian.

Above all, nobody would be appointed to serve in a dicastery without a doctorate in the relevant field, and experience in that area of ministry.

——

[1] The last being Teodolfo Martello, who was created cardinal while still a lay man, though he was ordained deacon two months later. At his death in 1899, he was last cardinal not to be either a presbyter or bishop. Since 1917 all cardinals were required to be ordained presbyters; since 1968 all were normally required to be ordained bishops.

Theology of the Laity – According to a Seminarian

Recently, I met with a visiting friend (who happens to be a canon lawyer) and we decided to sit in on Rome’s Theology on Tap, offered by some of the seminarians of the North American College to some of the study abroad programs that they work with for their “apostolates” (volunteer service giving them practice in some forms of ministry).

It is an interesting experience, to a professor of both U.S. undergrads and seminarians in Rome, because although neither the seminarians nor most of the undergrads present are in my classes, it still felt a little like I was listening to an oral presentation by one student that needed grading. I could not help myself.

The topic was “The Laity”. In fairness, my seat was in the back, so there were times it was hard to catch everything. But these are the points I heard:

- The Church teaches that priesthood and religious life (no mention of diaconate) are objectively a higher state than the laity. Subjectively, however, the universal call to holiness is equal for everyone in the Church.

- There is a difference between ministry and service. [Could not hear the definition]. Ministry is exercised only by the ordained. Lay people can only offer service. When you hear people talk about liturgical “ministry”, like a lector, this is really a service.

- The Lay Vocations are Marriage and Consecrated Life. Just as priests are committed to the Church, consecrated are committed to their communities, and married people are committed to each other.

- The Mission of the laity is exactly the mission of the whole church: Evangelization.

- [Missed something] You have the duty to correct your priests, professors, other leaders if you hear something wrong.

My canonist friend and I come from different cultures of Catholicism, but both have an ecclesial vocation, as lay people, in ministry and service to the Church. And while we had different objections to some of the points, we were in accord that, unfortunately, not everything represented well the Church’s teaching. The Church itself, of course, is not always consistently clear on this topic, which occasionally adds to the confusion.

First, he’s right on his penultimate point about the mission of the laity, which is the mission fo the Church. The laity are the vanguard of the Church’s mission, the clergy and other ecclesial ministers are there for support and leadership, but it is the laity whose first role is to go out into the world and get the real work of the Church done.

The final point might have been a reference to canon 212, by which all the faithful have the right, and are even obligated, to make their needs and concerns known to the Church according to their expertise. Consider this an exercise thereof to avoid similar mistakes by others.

Now the problematic points.Taken with a grain of salt, as i said, there was occasional cross-noise, so if i missed any clarifying comments or explanations to the points, the fault is mine.

The Church itself does not make use of this “objective”/”subjective” distinction in terms of a person’s state. All are equal in baptism. All are equally called to holiness, as he pointed out. Where there might be some confusion is in distinguishing the ways we participate in the One Priesthood of Christ. All who are Initiated (Baptized, Confirmed, Eucharist-ed) have a share in Christ’s priesthood. This is the universal priesthood, the priesthood of all believers. As priests, we are still equal. Lumen Gentium 10 says that these two kinds of participation in Christ’s priesthood “differ from one another in essence and not only in degree.” This seems to lend credence to the idea that one is higher. Avery Dulles, however, repeatedly pointed out it was better understood as “differing from one another in essence and not in degree,” that is, that they are different kinds of participation, but one is not higher than the other. Plus, we have only to look at scripture to see Jesus’ idea of leaders clamoring for a “higher status” – and it is not well received. Those called to leadership are called as servants.

Which goes to the distinction between ministry and service. As I missed something, its entirely possible he hit something right on, but the follow up was insufficient. The two words, in a Christian context, are both translations of diakonia. All ministry is service. Fair enough to say that not all service is ministry, but the distinction is not about ordained and lay, but about the nature of the service. Rather like the distinction between skills and charisms, wherein the later are always for the building up of the Body of Christ. Possible confusion comes from an infamous interdicasterial instruction that attempted to limit the term “ministry” to the ordained back in 1997, wherein this dichotomy was presented – yet every pope since (John Paul II, Benedict XVI, and Francis) have referred to lay ministry, as have most bishops conferences and other documents of the curia.

Finally on vocations. Put simply, everyone has a vocation. There are hardly only two options for lay people, and in fact, the two mentioned were only one kind of vocation – relationship – which is also called a state of life. Everyone also has a vocation to ministry/mission and to spirituality, at least. Some of the faithful are called to marriage, consecrated life, celibacy or single life. Some of the faithful are called to serve the church’s mission in the world, some as ecclesial ministers. Some of the former take vows, some enter into a sacramental relationship, though not all. Some of the later are ordained, though not all. Not all celibates are priests, not all priests are celibate. Not all lay people are married, and not all married people are lay. When talking vocations, it is confusing to try and force the square peg of relationship into the round hole of ministry.

But, that is one of the services offered by seminary, correction to mistaken ideas about the people you are called to serve.

On Priestly Celibacy and the Diaconate

This has been on my mind since the first minor flurry of stories about Pope Francis’ openness to discussion on the topic, based on the recounting of a single remark shared by Bishop Erwin Krautler of the Territorial Prelature of Xingu, Brazil. So, it is a lot of musing, but enough to get some conversations started, I hope.

First, an aside about numbers. Most accounts, like the RNS article linked above, cite 27 priests serving 700,000 Catholics, meaning a ratio of 1:25,925, a staggering reality if accurate.

However, I am not sure where these numbers come from. According to the Annuario Pontificio 2012, there are only 250,000 Catholics there, being served by 27 priests (about half diocesan and half religious), and according to Catholic-hierarchy.org, there are 320,000 Catholics (but only as of 2004). This means a ration of either 1:8620 (AP) or 1:13,333 (CH).

Still a staggering reality when you consider as frame of reference the following: The Archdiocese of Seattle, my home diocese, currently lists 122 active diocesan priests, 87 religious priests, and 31 externs borrowed from other dioceses serving a Catholic population of 974,000. This makes a priest to Catholic ratio of 1:4058 (the US average is just under 1:2000).

The Vicariate of Rome, my current diocese, has nearly 11,000 priests and bishops present, counting religious, externs, and curial staff. They are at least sacramentally available to the 2.5 million Catholics here. This makes a ratio of 1:234.

(Since priests were the subject of the article, I have left out deacons, catechists, and lay ecclesial ministers, as well as non-clerical religious, though not to discount their great service to the Church, to be sure!)

Even with the most conservative estimate of Xingu, the priests there are stretched more than twice as thin as their Seattle counterparts and 36x the scope of their Roman brethren.

What has really been on my mind, though, and again in the light of Pope Francis’ comments yesterday that the ‘door is always open’ to this change in discipline, is the effect that a sudden shift in allowing for a married presbyterate would have on the diaconate.

Some refreshers on basic points of the general discussion:

- We are only talking about diocesan (sometimes called secular) clergy, not religious. The latter would remain celibate under their vow of chastity, but diocesan clergy do not take such vows.

- We already have some married Catholic priests. Almost all of the Eastern Catholic Churches allow for both married and monastic clergy, and even in the Latin Church (i.e., Roman Catholic Church) we have married priests who were ordained as Anglicans or Lutherans, later came into full communion, and have been incorporated into Catholic holy orders.

- We do have celibate deacons, though not many. I have long held we need more celibate deacons and more married priests in the west, for various reasons.

- Most likely we would be talking about admitting married men to orders, rather than allowing priests to marry after ordination. This is the ancient tradition of the Church, east and west, since the Council of Nicaea when it was offered as a compromise between some who wanted celibacy as the norm, and others who thought it should not matter whether marriage or orders come first. We still have both extreme practices present in the Church today, however, so it is not impossible that we should choose a different practice. Unlikely, but possible.

- The Latin Church has maintained celibacy as a norm for its diocesan clergy since about the 12th century, though historians argue whether it was universally enforced until as late as the 16th. There are rituals as late as the 13th allowing for a place in procession for the bishop’s wife.

- Technically, it is currently the norm for all diocesan clergy, and any exceptions, including married deacons, are exceptions. Which begs the question, if it is so easy to make these exceptions for deacons, why not for priests?

- The Byzantine tradition has long held that bishops come from the monastic (celibate) clergy, whereas the Latin tradition has long held that bishops come from the diocesan clergy – which means we had married bishops when we had married priests and deacons. Given the situation with the Anglican Ordinariate, there seems to be a reluctance to return to this tradition, but as it was part of our Roman patrimony for a millennium, it seems it should be at least considered.

- Finally, it is not actually clerical, or priestly, celibacy per se that is at issue, but the idea of requiring celibacy of those to be ordained. There will always be room in the church for celibate deacons, presbyters, and bishops, and these charisms will always be honored. As it should be.

With all that in mind, I finally get to my point.

Let us imagine, unlikely though it may be, that tomorrow Pope Francis announces we will no longer require celibacy of our candidates for orders – whether deacon, presbyter, or bishop. The most immediate effect and response of the faithful, and the press, will be about the change in the discipline of priestly celibacy.

If it is done that directly, it would be disastrous for the diaconate. Many men, I have no doubt, have been ordained to the diaconate simply because they or their bishops saw no alternative for someone called to both marriage and ordained ministry. Many may in fact be called to the presbyterate instead, and given the opportunity, ‘jump ship’ from one order to the other.

One can likewise imagine there are many currently in the presbyterate who are actually called to the diaconate, but they or their bishop saw no reason for not ordaining them to the presbyterate because they were called to celibacy as well. I have heard many a bishop say something along the lines of, ‘why be ordained a celibate deacon? If you can be a priest, we need that more!’

Without completing the restoration of the diaconate as a full and equal order, and a better understanding of both orders separated out from the question of marriage/celibacy, what will happen is a return to the ‘omnivorous priesthood’ and an ecclesiology of only one super-ministry. Rather than a plethora of gifts and ministries as envisioned in the Scriptures, lived in the early church, and tantalizingly promised at Vatican II, everyone would flock to the presbyterate and we would have set back some aspects of ecclesiological reform half a century.

Rather than simply a change to the discipline of clerical celibacy, what is needed is a comprehensive reform of ministry in the Church. Tomorrow Pope Francis could say, instead, ‘Let’s open the conversation. Over the next three years, we will look at the diaconate and the presbyterate, lay ecclesial ministry and the episcopate, and we will consider the question of celibacy in this context. At the end of this study period, a synod on ministry.’

What I would hope to come out of this would be first a separation of two distinct vocational questions that have for too long been intertwined: ecclesial ministry on one hand and relationships on the other. We have been mixing apples and oranges for too long, but priesthood or diaconate is an apple questions, and marriage or celibacy is an orange question.

The deacons, traditionally, are the strong right arm of the bishop. Make it clear that deanery, diocesan, and diplomatic tasks (and the Roman curia for that matter) are diaconal offices. In need, a qualified lay person could step in, or rarely a presbyter, but these are normatively for deacons. This also makes it obvious why we need more celibate deacons, such as in the case of the papal diplomatic corps. They tend to be younger and more itinerant, needed wherever the bishop sends them.

Presbyters are traditionally parish pastors and advisors of, rather than assistants to, the bishop. As the deacon is sent by the bishop, the pastor ought to be chosen from and by the people he serves.. He should be a shepherd who smells like his sheep, right? How exactly this looks can take various forms, to be sure the bishop cannot be excluded, but the balance of ministerial relationships should show clearly that the presbyter is more advisor to the bishop and minister among the people he is called to serve, and the deacon is the agent of the bishop. At least one should not be ordained until there is an office to which he is called which requires his ordination This also makes it obvious why presbyters can, and often are in other churches, married. They tend to be more stable and older.

The minimum age for ordination should be the same for both orders, regardless of marriage or celibacy, and in general one can imagine that deacons would be younger than presbyters. Let the elders be older, indeed!

Some deacons may even find, later in life, reason or office to transition to the presbyterate, but otherwise there should be no such thing as a transitional diaconate. Candidates for both orders should spend at least five years, perhaps more, in lay ecclesial ministry, before being ordained, as long as this does not reduce lay ministry to a transitional step only, as a similar move did to the diaconate all those centuries ago!

Bishops could be chosen from either order, and be either married or celibate. Indeed, celibacy should be rejoined with the rest of the monastic ideal, and there should be no such thing as a celibate without a community. It need not be a community of other permanent celibates or of other clergy – there are some great examples, such as the Emmanuel Community in France, who have found ways for celibate priests to live in an intentional Christian community that includes young single people, deacons, lay ecclesial ministers, etc.

Bottom line, if it is just a conversation about priesthood, as much as mandatory celibacy needs to be discussed openly and without taboo, it is not enough. It must be a holistic discussion about ministry, and the diaconate has a special place in this conversation given its recent history and current experience. We have such a deep and broad Tradition from which to draw, why would we not dive in to find ancient practices to suggest modern solutions?

Vocations and Ministries

Behold, I stand at the door and knock.

If anyone hears My voice, and opens the door,

I will come unto him and dine with him and him with me.

Revelation 3:20

Pulled from the archives, i found this file on vocations, created for one of scouting’s religious emblems programs. I cannot for the life of me find the original attribution, if there was one, but we made several adaptations anyway. This version was prepared by me, for the Archdiocesan Committee on Catholic Scouting in Seattle, several years ago. Still worth a reminder: there’s more to vocation than priests and nuns.

There was a time when, if somebody said the word “vocation”, people would think mainly of “priests and nuns”. However, the Catechism of the Catholic Church defines vocation as “The calling or destiny we have in this life and hereafter.” Today the church clearly uses the term to refer to the calling each of us has to use our God-given gifts to participate in the mission and ministry of the Church: All Christians have a vocation.

Each person’s vocation has three components: The first part is the call to faith. The second is the call to relationship. The third is the call to ministry.

The call to faith is sometimes referred to as the ‘universal call to holiness’: “All Christians in any state or walk of life are called to the fullness of Christian life and to the perfection of charity.” (Lumen Gentium 40 §2). We are all called to be the best Christians we can be, with the help of the gifts God has given us. We are called to love one another, to practice justice and charity, to help those most in need, and to transform ourselves and the world around us to be more like Christ. This is more than asking ourselves, “What would Jesus do?” It involves asking “Who does Jesus want me to be?”

The call to relationship is sometimes referred to as your ‘state of life’. Each of us is called to love everyone around us. But, we obviously do not love everyone in the same way. The call to relationship is about how we love the people around us, how we are in relationship with other people. Some people are called to marry and raise a family. Some are called to take vows and live in a religious community with other people who make the same vows. Some are called to remain single for life and not get married (this is called celibacy). Most people spend several years as single persons before committing to marriage, religious life, or celibacy.

The call to ministry is probably what most people mean when they talk about vocations. This is about what you do as a member of the church, and how you participate in the mission of the Church. The Church’s mission is to carry on the mission of Christ: Proclaim the good news of God’s saving love for all people; to establish a prayerful community of believers; and to serve the needs others, especially the poor and marginalized. Through our initiation by Baptism, Confirmation, and Eucharist, each member of the church takes responsibility to carry out this mission of Christ in partnership with other church members.While everyone is called to contribute to the common mission of the church, not everyone is called in the same way. After all, we each have different gifts and talents.

Within the call to ministry there are two essential groups:Lay ministries and ecclesial ministries.

Lay ministries are sometimes called ‘the lay vocation’ or ‘the lay apostolate’. The word “lay” comes from the Greek term laos theon (People of God). The people whose calling is to lay ministry are called “the laity” or “lay people”. They are the people chiefly responsible for the mission of the Church in the world. This includes evangelizing (bringing non-believers into relationship with Jesus), doing works of charity for the poor, advocating for justice to eradicate poverty, and transforming the world so it is more like Christ. With such a big job, it’s a good thing that 99.7% of all Catholic Christians are called to lay ministry!

Ecclesial ministries get their name from the Greek word ekklesia which means ‘assembly’ or ‘church’. It basically means official church ministries. Ecclesial ministers serve the pastoral and spiritual needs of the Church members by preaching, teaching, and sanctifying (inspiring others to holiness). They are often, but not always, the most visible leaders within the church and most are employed full-time by the church. Some are ordained (Bishops, Presbyters, and Deacons) but others are not (Theologians and Lay Ecclesial Ministers). They make up the remaining 0.3% of the Church’s members.

It is always important to remember that “there is a variety of gifts but always the same Spirit; there are many types of service to be done, but always the same Lord, working in many different kinds of people; it is the same God who is working in all of them.” (1 Corinthians 12.4-6) In other words, each vocation is different, but they are all equal.

This section lists a variety of currently recognized ministries in the Catholic Church in Western Washington. It is not complete: New ways of serving God’s people are constantly developing as needs are identified and awareness is sharpened. Traditional church roles can take on new characteristics as the culture and social climate changes.

Ecclesial Ministries (ordained)

- Bishop

- Archbishop; Auxiliary Bishop; Retired Archbishop

- Presbyter (Priest)

- Vicar General; Episcopal Vicar; Dean; Pastor; Priest Moderator; Priest Administrator; Parochial Vicar; Chaplain

- Deacon

- Archdeacon, Protodeacon, Pastoral Coordinator; Pastoral Associate; Pastoral Assistant

Ecclesial Ministries (non-ordained)

- Theologian

- University/College Theology Professor; Archdiocesan Theological Consultant; Author (of theological books/articles)

- Lay Ecclesial Minister

- Archbishop’s Delegate; Chancellor, Ecumenical Officer, Pastoral Life Director; Pastoral Coordinator; Pastoral Associate; Pastoral Assistant; Catholic School Principal; Youth Ministry Coordinator; Campus Minister; Prison Minister; Hospital Minister; Missionary; High School Religion Teacher; Catholic Elementary School Teacher; Lay Presider; Lay Preacher

Lay Ministries (Instituted)

- Acolyte

- Reader

Lay Ministries

- Liturgy ministers

- Altar Server; Cantor; Choir; Eucharistic Minister (Extraordinary Minister of Communion; Lector; Master of Ceremonies; Musician; Sacristan;

- Catechists

- Baptism preparation; Bible Study leader; Catholic media (journalists, bloggers, etc); Faith Formation/CCD teacher; Confirmation preparation; CYO camp staff; Engaged Encounter team; Evangelization team; First Communion preparation; First Reconciliation preparation; Religious emblems facilitator; RCIA team; SALT; Scout leader; Young adult ministry; youth ministry

- Consultative Leadership

- Diocesan Synod, Pastoral Council, Finance Council, Liturgy Commission, Ecumenical Commission, Faith Formation Commission, Social Justice/Outreach Commission, Parish School Board/Commission

- Social Justice and Pastoral Care ministries

- Annulment Advocate; Cabrini Ministry; Catholic Community Services worker; Catholic Relief Services worker; Catholic Worker member; Food Bank volunteer; Grief minister; Hospice minister; Hospitality minister; Jesuit Volunteer Corps; Just-Faith/Justice Walking; L’Arch Community; Mission trip; Parish Nurse; Parish Counselor; Peer Minister; Pro-Life advocate; Sant’Egidio, St. Joseph’s Helpers; St. Vincent de Paul; Visitor to sick and elderly;

- Spirituality and Devotions

- Communion and Liberation; Cursillo; Faith Sharing group leader; Focolare, Marriage Encounter; Retreat leader; Returning Catholics team; Spiritual Director; Spiritual Coach; Stephen’s Ministry

States of Life/Call to Relationship

- Vowed Life

- Marriage

- Religious vows (monastics [monks, nuns], mendicants)

- Consecrated Life

- Consecrated Virgin, Hermit, Opus Dei Numerary, “Brothers”, “Sisters”, members of some lay movements

- Promised Life

- Celibacy

- Engaged/Betrothed persons

Almost Reverend

I originally posted this a couple of years ago on a different blog. I came accross it recently, and given where i am now (that is, Rome), it still seems funny, and i hope you can appreciate the humor. [Disclaimer: No clerics were harmed in the making of this post.]

**Original Post: August 15, 2008**

At an ecumenical meeting not long ago, i found myself again trying to explain lay ecclesial ministry to a Lutheran pastor. While many non-Catholics (and even some Catholics) often think the only ministers in the Catholic Church are priests, at least this one had been ecumenically involved long enough to know different. He just was not sure how to address me.

“As a member of the Board,” he said, “you deserve to be addressed with appropriate formality in correspondence, and appropriate respect during meetings. So, what do we call you?”

I told him the name given me at my birth and baptism was Andrew, and that was fine – or A.J., as I have been known since birth: “No adornments necessary.”

Pressed, however, I shared how evangelical Christians i meet with invariably address me as “Pastor Boyd”, since anyone who does professional pastoral ministry is, ipso facto, a pastor, and therefore called “pastor”. I noted how, every time i got something from Hilel or the local synagogue, it was addressed to “Rev. Boyd”, because, again, the logic is, clergy are professional ministers, and I am a professional minister, so i must be clergy. Even when filling out legal forms, i often have to select “clergy” as my occupation, because for the uninitiated, clergy is defined by Webster, and not the Codex Iuris Canonicis, as “a group of church officials doing official church ministry”.

After all this, i was informed it just was not acceptable. We had to find something appropriate to my position as not-ordained but vocational, “professional” minister of the Church while respecting the internal distinction between clerical and lay ministers. So we began an exploration.

“Virtually Reverend”, “Not-Quite-Reverend”, and “Sort-of-Reverend” were all suggested before we alighted on “The Almost Reverend”.

After my colleague observed that a personal style was needed, too, I remembered a line from a great book and movie about a pope, Saving Grace, and we decided the only possible ecclesiastical style for someone of such standing as myself was “Your Mediocreness…”

Therefore I can now fit in at the next clerical cocktail party as “His Mediocreness, The Almost Reverend A. J. Boyd”.

I am thinking of petitioning the Pontifical Council for the Laity for making this a universal norm…