Year of Faith Calendar

The 50th anniversary of Vatican II first session is being celebrated in Rome by a ‘Year of Faith.’ Edward Pentin of the National Catholic Register collated most of the events, below.

BY EDWARD PENTIN, ROME CORRESPONDENT

With just two months to go until the Year of Faith begins, the Vatican has released a calendar of all the major meetings, celebrations and initiatives taking place in Rome.

The events, which are aimed at deepening the diverse religious and cultural themes related to the yearlong celebration, begin shortly before the official opening on Oct. 11, according to the calendar compiled by L’Osservatore Romano and published Aug. 1.

The Court of the Gentiles will be holding a meeting of dialogue between believers and nonbelievers in Assisi Oct. 6, followed by the opening of the XIII General Assembly of the Synod of Bishops on Oct. 7 at the Vatican. The synod will last until Oct. 28.

The Pope is then to formally open the Year of Faith at a solemn celebration in St. Peter’s Square, beginning at 10am on Oct. 11. The Holy Father will be joined by the Synod Fathers and presidents of the world’s bishops’ conferences. In the evening, the Italian Catholic movement L’Azione Cattolica will hold a procession from Castel Sant’Angelo to St. Peter’s Square to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the opening of the Second Vatican Council.A large number of events will then begin to take place over the next 12 months, all emphasizing the meaning of faith and evangelization. These include a meeting on the theme “The Faith of Dante,” an artistic and cultural evening that will take place at the Jesuit Chiesa del Gesu in Rome Oct. 12, partly organized by the Pontifical Council for Culture.

On Oct. 20, a pilgrimage and vigil for missionaries will take place on the Janiculum hill close to the Vatican, organized by the Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples.

The following day, Sunday Oct. 21, Benedict XVI will preside over the canonization of six martyrs and blesseds: Jacques Barthieu, a Jesuit missionary, martyred in Madagascar in 1896; Pietro Calungsod, a lay catechist, martyred in the Philippines in 1672; Giovanni Battista Piamarta, an Italian priest who founded the Congregation of the Holy Family of Nazareth for men and the Humble Servants of the Lord for women, who died in 1913; two Americans: Blessed Marianne Cope of Molokai, who spent 30 years ministering to lepers on the Hawaiian island of Molokai; and Blessed Kateri Tekakwitha, a native American, baptized by a Jesuit missionary in 1676 when she was 20, who died four years later; Blessed Carmen Salles y Barangueras, a religious in Spain who worked with disadvantaged girls and prostitutes and died in 1911; and Anna Schäffer, a lay Bavarian woman who accepted her infirmity as a way of sanctification, who died in 1925.

Then, Oct. 26-30, a congress of the World Union of Catholic Teachers will take place in Rome, focusing on the role of the teacher and the family in the integral formation of students, with the participation of the Congregation for Catholic Education.

Nov. 15-17, the 27th International Conference of the Pontifical Council for Health Care will be held on the theme “The Hospital, a Place of Evangelization: the Human and Spiritual Mission.”

After the Holy Father celebrates the first vespers of Advent for the pontifical universities in Rome and other institutes of formation on Dec. 1, an exhibition on the Year of Faith will be inaugurated Dec. 20 in Castel Sant’Angelo. The exhibition will last until May 1, 2013.

As is tradition, an ecumenical prayer service with Pope Benedict will take place Jan. 25, 2013, at the Basilica of St. Paul Outside the Walls, but next year’s celebration on the Solemnity of the Conversion of St. Paul will also see an art exhibit on display in the basilica until Nov. 24; it is entitled Sanctus Paolus Extra Moenia et Concilium Oecumenicum Vaticanum II.

On Feb. 2, Benedict XVI will celebrate the World Day of Men and Women Religious in St. Peter’s; and a Feb. 25-26 symposium, “Sts. Cyril and Methodius Among the Slavic Peoples: 1,150 Years From the Beginning of the Missions,” will take place at the Pontifical Oriental Institute and the Pontifical Gregorian University.

On March 24, Benedict XVI will celebrate Palm Sunday, a day traditionally offered for young people in preparation for World Youth Day.

Between April 4-6, the Congregation for Catholic Education will co-host an international conference as part of the celebration.

A concert, “Oh My Son,” will be performed in the Paul VI Hall April 13, while, from April 15-17, the Congregation for Catholic Education will be organizing a study day to discuss the relevance of the documents of Vatican II and the Catechism of the Catholic Church in the formation of candidates for the priesthood and in the ongoing revision of the Ratio Fundamentalis Institutionis Sacerdotalis (Spiritual Formation in Seminaries).

April 28 will be a day dedicated to all boys and girls who have received the sacrament of confirmation; the Holy Father is scheduled to confirm a small group of young people on this day. On May 5, the Pope will celebrate a day dedicated to confraternities and popular piety.

On the vigil of Pentecost, May 18, the Pope will dedicate the celebrations to all the faith-based movements, together with pilgrims at the tomb of Peter, and invoke the Holy Spirit. June 2, the feast of Corpus Domini, will be a day of solemn Eucharistic adoration, presided by the Pope. As part of the Year of Faith, adoration will take place throughout the world.

A day dedicated to Blessed Pope John Paul’s 1995 encyclical Evangelium Vitae will take place June 16, in the presence of the Pope. It will be dedicated to the witness of the gospel of life, to the defense of the dignity of the person from conception to natural death.

Vocations and Ministries

Behold, I stand at the door and knock.

If anyone hears My voice, and opens the door,

I will come unto him and dine with him and him with me.

Revelation 3:20

Pulled from the archives, i found this file on vocations, created for one of scouting’s religious emblems programs. I cannot for the life of me find the original attribution, if there was one, but we made several adaptations anyway. This version was prepared by me, for the Archdiocesan Committee on Catholic Scouting in Seattle, several years ago. Still worth a reminder: there’s more to vocation than priests and nuns.

There was a time when, if somebody said the word “vocation”, people would think mainly of “priests and nuns”. However, the Catechism of the Catholic Church defines vocation as “The calling or destiny we have in this life and hereafter.” Today the church clearly uses the term to refer to the calling each of us has to use our God-given gifts to participate in the mission and ministry of the Church: All Christians have a vocation.

Each person’s vocation has three components: The first part is the call to faith. The second is the call to relationship. The third is the call to ministry.

The call to faith is sometimes referred to as the ‘universal call to holiness’: “All Christians in any state or walk of life are called to the fullness of Christian life and to the perfection of charity.” (Lumen Gentium 40 §2). We are all called to be the best Christians we can be, with the help of the gifts God has given us. We are called to love one another, to practice justice and charity, to help those most in need, and to transform ourselves and the world around us to be more like Christ. This is more than asking ourselves, “What would Jesus do?” It involves asking “Who does Jesus want me to be?”

The call to relationship is sometimes referred to as your ‘state of life’. Each of us is called to love everyone around us. But, we obviously do not love everyone in the same way. The call to relationship is about how we love the people around us, how we are in relationship with other people. Some people are called to marry and raise a family. Some are called to take vows and live in a religious community with other people who make the same vows. Some are called to remain single for life and not get married (this is called celibacy). Most people spend several years as single persons before committing to marriage, religious life, or celibacy.

The call to ministry is probably what most people mean when they talk about vocations. This is about what you do as a member of the church, and how you participate in the mission of the Church. The Church’s mission is to carry on the mission of Christ: Proclaim the good news of God’s saving love for all people; to establish a prayerful community of believers; and to serve the needs others, especially the poor and marginalized. Through our initiation by Baptism, Confirmation, and Eucharist, each member of the church takes responsibility to carry out this mission of Christ in partnership with other church members.While everyone is called to contribute to the common mission of the church, not everyone is called in the same way. After all, we each have different gifts and talents.

Within the call to ministry there are two essential groups:Lay ministries and ecclesial ministries.

Lay ministries are sometimes called ‘the lay vocation’ or ‘the lay apostolate’. The word “lay” comes from the Greek term laos theon (People of God). The people whose calling is to lay ministry are called “the laity” or “lay people”. They are the people chiefly responsible for the mission of the Church in the world. This includes evangelizing (bringing non-believers into relationship with Jesus), doing works of charity for the poor, advocating for justice to eradicate poverty, and transforming the world so it is more like Christ. With such a big job, it’s a good thing that 99.7% of all Catholic Christians are called to lay ministry!

Ecclesial ministries get their name from the Greek word ekklesia which means ‘assembly’ or ‘church’. It basically means official church ministries. Ecclesial ministers serve the pastoral and spiritual needs of the Church members by preaching, teaching, and sanctifying (inspiring others to holiness). They are often, but not always, the most visible leaders within the church and most are employed full-time by the church. Some are ordained (Bishops, Presbyters, and Deacons) but others are not (Theologians and Lay Ecclesial Ministers). They make up the remaining 0.3% of the Church’s members.

It is always important to remember that “there is a variety of gifts but always the same Spirit; there are many types of service to be done, but always the same Lord, working in many different kinds of people; it is the same God who is working in all of them.” (1 Corinthians 12.4-6) In other words, each vocation is different, but they are all equal.

This section lists a variety of currently recognized ministries in the Catholic Church in Western Washington. It is not complete: New ways of serving God’s people are constantly developing as needs are identified and awareness is sharpened. Traditional church roles can take on new characteristics as the culture and social climate changes.

Ecclesial Ministries (ordained)

- Bishop

- Archbishop; Auxiliary Bishop; Retired Archbishop

- Presbyter (Priest)

- Vicar General; Episcopal Vicar; Dean; Pastor; Priest Moderator; Priest Administrator; Parochial Vicar; Chaplain

- Deacon

- Archdeacon, Protodeacon, Pastoral Coordinator; Pastoral Associate; Pastoral Assistant

Ecclesial Ministries (non-ordained)

- Theologian

- University/College Theology Professor; Archdiocesan Theological Consultant; Author (of theological books/articles)

- Lay Ecclesial Minister

- Archbishop’s Delegate; Chancellor, Ecumenical Officer, Pastoral Life Director; Pastoral Coordinator; Pastoral Associate; Pastoral Assistant; Catholic School Principal; Youth Ministry Coordinator; Campus Minister; Prison Minister; Hospital Minister; Missionary; High School Religion Teacher; Catholic Elementary School Teacher; Lay Presider; Lay Preacher

Lay Ministries (Instituted)

- Acolyte

- Reader

Lay Ministries

- Liturgy ministers

- Altar Server; Cantor; Choir; Eucharistic Minister (Extraordinary Minister of Communion; Lector; Master of Ceremonies; Musician; Sacristan;

- Catechists

- Baptism preparation; Bible Study leader; Catholic media (journalists, bloggers, etc); Faith Formation/CCD teacher; Confirmation preparation; CYO camp staff; Engaged Encounter team; Evangelization team; First Communion preparation; First Reconciliation preparation; Religious emblems facilitator; RCIA team; SALT; Scout leader; Young adult ministry; youth ministry

- Consultative Leadership

- Diocesan Synod, Pastoral Council, Finance Council, Liturgy Commission, Ecumenical Commission, Faith Formation Commission, Social Justice/Outreach Commission, Parish School Board/Commission

- Social Justice and Pastoral Care ministries

- Annulment Advocate; Cabrini Ministry; Catholic Community Services worker; Catholic Relief Services worker; Catholic Worker member; Food Bank volunteer; Grief minister; Hospice minister; Hospitality minister; Jesuit Volunteer Corps; Just-Faith/Justice Walking; L’Arch Community; Mission trip; Parish Nurse; Parish Counselor; Peer Minister; Pro-Life advocate; Sant’Egidio, St. Joseph’s Helpers; St. Vincent de Paul; Visitor to sick and elderly;

- Spirituality and Devotions

- Communion and Liberation; Cursillo; Faith Sharing group leader; Focolare, Marriage Encounter; Retreat leader; Returning Catholics team; Spiritual Director; Spiritual Coach; Stephen’s Ministry

States of Life/Call to Relationship

- Vowed Life

- Marriage

- Religious vows (monastics [monks, nuns], mendicants)

- Consecrated Life

- Consecrated Virgin, Hermit, Opus Dei Numerary, “Brothers”, “Sisters”, members of some lay movements

- Promised Life

- Celibacy

- Engaged/Betrothed persons

The Bible plus: The four books of Mormonism | The Christian Century

Reposted from The Bible plus: The four books of Mormonism | The Christian Century.

If you haven’t read this yet, a very helpful and concise review of LDS scripture.

The Bible plus:

The four books of Mormonism

A Latter-day Saint friend of mine once invited an evangelical coworker to church. The coworker found much that was familiar in the LDS service: hymn singing, an informal sermon style, robust fellowshiping and scripture-driven Sunday school. But then came the moment when the Sunday school teacher, after beginning with Genesis, said “Let’s now turn to the Book of Moses” and began reading: “The presence of God withdrew from Moses . . . and he said unto himself: Now, for this cause I know that man is nothing, which thing I never had supposed.’” I am told that the visitor reflexively searched through his Bible before he realized that he’d never heard of such a book, though of course the story of the burning bush was familiar. And while he didn’t mind the sentiments expressed in the words he’d heard, he knew that they were not in his Bible.

This mix of the familiar and the strange is a common experience for any who have spent even minimal time with the Latter-day Saints. The greatest contributing factor to this mix is Mormonism’s dependence on and sophisticated redaction of the Bible. All of Mormonism, even its most unfamiliar tenants, rests in some element of the biblical narrative. Academics would explain this in terms of intertextuality, noting that the meanings of Mormonism, even its unique scriptures, are achieved within the larger complex of the Christian canon. You don’t need to be a scholar to recognize this. You need only open and read the first words you see in any one of Mormonism’s unique scriptures.

The Latter-day Saint canon consists of four books: the Bible and three other texts—the Book of Mormon, the Book of Doctrine and Covenants and the Pearl of Great Price. Each reads very much like the Bible in type and breadth of thematic concerns and literary forms (history, law, psalm). Even the rhetorical stance of each canon is biblical: God is speaking to prophets faced with temporal crises of spiritual significance. In terms of the authority granted these four texts, all have equal weight, including both Bible testaments, as historical witnesses to God’s promise of salvation, enacted by covenant with the Israelites and fulfilled in the atonement of Jesus Christ as the only begotten of the Father.

The LDS Church’s confidence in the authority and historicity of the Bible is mitigated only by scruples regarding the Bible’s history as a book. The Bible is “the word of God insofar as it is translated correctly.” The other three Latter-day Saint scriptures are also believed to be historical witnesses to God’s promise of salvation. Considered translations by or direct revelation to Joseph Smith, the church’s founding prophet, they are considered correct in their representation of God’s will and word, though they possibly contain flaws resulting from “the mistakes of men.” What follows is a brief description of these three texts and a few examples of how they reshape Christian tradition and influence Latter-day Saint belief and practice.

The Book of Mormon is the narrative of a prophet-led people’s experience with God over a thousand-year period, beginning with the flight of two Israelite families from Jerusalem in the sixth century BCE on the eve of Babylonian captivity. The people of God eventually create a complex civilization in the Western Hemisphere. The story is a cautionary tale of cycles of conversion and backsliding. It concludes in approximately the fourth century CE with an account of wickedness and consequent destruction. The climax of the narrative occurs midway with the appearance of Jesus Christ immediately after his resurrection to a chastened remnant in the Americas who are taught by him to repent, embrace the gospel and establish a church. Thus, the Book of Mormon not only echoes the narrative style and certain contents of the Bible, such as the Beatitudes, but also functions as second witness to the Bible’s testimony that Jesus is the source of salvation for all.

The Book of Mormon clearly deviates from Christian tradition by not limiting Christ’s ministry to a particular people and time. The rejection of such limitations is one of the book’s main points. The claim that “we need no more Bible” is made the object of God’s rebuke: “Know ye not that there are more nations than one? . . . because that I have spoken one word ye need not suppose that I cannot speak another.” Clearly, the Book of Mormon’s purpose is not only to second the biblical witness but also to evidence the ongoing revelation of the gospel. Notwithstanding its orthodox representation of that gospel, the Book of Mormon takes a position on certain historic theological questions. For example, while teaching the reality and catastrophe of the Fall, the prophets of the Book of Mormon reject notions of human creatureliness and depravity. Humans are not utterly foreign to God’s being. They are inherently made capable of acting for good, though only through Christ’s sacrifice is this capacity liberated from the enslaving effect of the Fall on human will. It is “by grace we are saved after all we can do.” Thus in Mormonism God’s economy of salvation is broad, though not universal in its promise of glory. Humans are prone to sin, free to reject grace and may fall from grace. Nevertheless, grace is freely given to those who in faith repent.

The LDS Church’s third canonical text, the Book of Doctrine and Covenants, is composed of revelations received largely by Joseph Smith between 1830 and 1844. Essentially a book of order and doctrine, it is the most discursive of the church’s scriptures. Again, much is familiar to non-Mormons, such as believer’s baptism, confirmation through the laying on of hands for the gift of the Holy Spirit, and affirmations such as “justification through the grace of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ is just and true. “ Less conventional but still acceptable is the book’s emphasis on sanctifying endowments of heavenly power “through the grace of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ . . . to all those who love and serve God with all their mights, minds and strengths.” For example, the D&C contains a version of the catalogue of the gifts of faith in 1 Corinthians, all of which are embraced within Mormonism.

LDS Church offices, too, are initially familiar: deacon, teacher, priest, elder and bishop. But the church’s charismatic offices, such as high priest, apostle and prophet, are unfamiliar in a modern context. Particularly indicative of the canon’s sanctification of the Christian life is the D&C’s provision for an ordained priesthood of all believers authorized to perform every ordinance as well as all pastoral and preaching duties.

The D&C contains a number of teachings, especially related to temple worship, that are unique to the Latter-day Saints. Space permits discussion of only one: saving ordinances, such as baptism and confirmation, performed not only for the living but also by proxy for the dead. D&C 124 describes this practice and provides a good illustration of the way in which the LDS Church’s canon leverages biblical concepts to create beliefs outside the tradition as if from within it. This text explicitly roots baptism by proxy for the deceased in Matthew 16’s reference to authority that can “bind” heavenly possibilities by earthly acts. It further grounds the doctrine in 1 Corinthians’s rhetorical question: “Now if there is no resurrection, what will those do who are baptized for the dead? If the dead are not raised at all, why are people baptized for them?”

D&C 124 claims that the answer to Paul’s question comes as deeply from within the tradition as does the question itself. First, it refers to Malachi’s promise that Elijah would come to “turn the hearts of the parents to their children, and the hearts of the children to their parents.” Smith claimed that Elijah had returned in 1836 to restore the heavenly keys to such a turning of hearts, an event recorded in D&C 110. This turning—or, as Smith termed it, binding—of the generations by sanctifying covenants with God animates the church’s genealogy program, as well as its practice of sealing marriages for eternity.

Second, the biblical imperative of Hebrews 11 is cited in D&C 124 to show the necessity of this sacramental work on behalf those who died without the gospel: “For their salvation is necessary and essential to our salvation, as Paul says concerning the fathers—that they without us cannot be made perfect—neither can we without our dead be made perfect.” Though Latter-day Saints believe that the deceased may reject grace and nullify the sacraments performed on their behalf, providing the option is the duty of the faithful to those who were without the gospel in this life.

Innumerable examples can be given of Mormonism’s canonical similarities and dissimilarities with traditional Christianity. By employing both biblical forms and hermeneutic, Latter-day Saint scripture is profoundly adaptive of historic Christianity’s theological traditions. To fully understand this phenomenon, however, one more aspect of Mormonism’s extended canon needs to be considered. Notwithstanding the D&C’s tendency to discourse, the most powerful force at work in Latter-day Saint differentiation is the narrative function of its canon. The Pearl of Great Price is the obvious case in point, though in a more subtle way it is true of the Book of Mormon as well.

The Pearl of Great Price is a compendium of several writings attributed to Joseph Smith’s revelatory powers. The two largest portions are called the Book of Moses and the Book of Abraham. Both books include a retelling of the creation story. Most significantly, this retelling includes an event before creation in which God met with his children regarding the next step in their existence. This step required the gift of more expansive powers of agency in order to learn by experience to distinguish good from evil, thus enabling human progress to higher levels of being.

The event is characterized by two contrasting concepts of how earthly existence should be ordered. The contender for one concept insisted on the use of force to ensure that humans made the right choice. The other advocated God’s original plan that offered salvation from wrong choices through sacrificial atonement. This advocate further agreed to be the sacrifice, leaving the glory to God. As you no doubt have guessed, the first contender is Lucifer, who rebelled against God, lost whatever light his name suggests and became the devil. The second petitioner became God’s only begotten son, and by virtue of his redemptive power became in all ways like God the Father.

God’s challenge to Job’s memory and his call to Jeremiah, as well as Isaiah’s lament and Paul’s dictum in Romans, may supply biblical evidence for the premortal existence of humankind. But canonization of a Bible-like narrative that directly counters the theological tradition of creation ex nihilo is one of the most provocative aspects of Mormonism. Some non-Mormons have been so provoked as to accuse the Latter-day Saints of believing the devil is a brother of Jesus in the sense that they share the same nature and power. This could not be further from the church’s canon and teachings regarding the divinity of Christ. Regardless, the belief that sacred history extends to a premortal existence for human life and to events before creation has a definitive affect on Mormons’ self-understanding and their sense of time and eternity. It is fundamental to their answer to the classic existential question, Where did we come from?

The two other questions that preoccupy religious thought are why are we here and where are we going, and the Saints’ extended canon tackles these questions as well. As noted by the Sunday school teacher mentioned earlier, the Pearl of Great Price contains an account of Moses’ theophany on Mount Horeb. The prophet is depicted as having been amazed at his nothingness after being shown the earth and its inhabitants. But he is not so dumbfounded that he fails to ask God why these creations exist, and he receives this answer: “There is no end to my works, neither to my words. For behold, this is my work and my glory—to bring to pass the immortality and eternal life of man.”

This short verse defines God in terms of his capacity to “bring to pass” or engender in his children the quality of the life he possesses—“immortality and eternal life.” The verse contravenes centuries of Christian theological anthropology that insists there is an unbridgeable ontological gulf between God and humankind. Or, in more technical terms, traditional Christianity teaches that God’s nature is fundamentally unrelated to human nature—the one uncreated, the other created. The Latter-day Saint canon asserts to the contrary that God is best understood by his fundamental relatedness, his fatherhood.

The effect of this view on the Latter-day Saints’ identity is probably immeasurable. They believe that God has known them, as he said to Jeremiah, before they were in the womb and that they are, if faithful, predestined for glory in Pauline terms. When things get tough, as in the case of Job, the Saints are to remember the time when “the morning stars sang together” about what they believe was a loving Father’s plan for their ultimate glory. On the basis of these alternative accounts of creation and Moses’ theophany, Latter-day Saints believe that the truest measure of God’s greatness is his generativity, not his sovereignty or prescient omniscience that predestines outcomes. Thus, when they voice their Christian perfectionism in terms of becoming like God, Latter-day Saints are not aspiring to power over others. As we have seen, the primordial event in their canon’s salvation history uses Lucifer’s fate as a warning against such aspiration. Rather, they understand their divine potential in terms of parenting, even the promise of an endowment of sanctifying grace that enables the faithful to facilitate spiritual, not merely physical, birth. To obtain such generativity is, for Latter-day Saints, why humans exist, and it constitutes the deep doctrinal stratum of what is typically seen as merely a sentimental attachment to family.

As for the third existential dilemma—where we are going—Latter-day Saint scripture elaborates on John 5 and 1 Corinthians 15 to affirm a variety of degrees of glory to which virtually all of God’s children will be raised after judgment. D&C 76 is the most complete discourse on this subject, and it incorporates the Pauline metaphors of sun, moon and stars to describe the varieties of glory in the afterlife. The effect is, in part, to counter the idea of a one-size-fits-all heaven capable of accommodating the varieties of human desire and action. Rather, it is hell that lacks diversity, accommodating only “those sons of perdition who deny the Son after the Father has revealed him . . . crucified him unto themselves and put him to open shame.” The rest of humanity “shall be brought forth . . . through the triumph and the glory of the Lamb, who was slain, who was in the bosom of the Father before the worlds were made. And this is the gospel, the glad tidings.” Thus, in Latter-day Saint eschatology there are many degrees of glory or “mansions” (to use John 14 KJV, since it better conveys the idea of glory than does the NIV’s “rooms”), but hell is an undiversified site with a narrowly defined population. As a consequence of these scriptural differences, Latter-day Saints do not judge religious differences as meriting consignment of people to hell, nor do they threaten nonbelievers with such a fate.

Narrative remains the preferred method of conveying Latter-day Saint teachings, however—even in eschatological matters. D&C 138 contains an account of Christ’s visit to the world of spirits mentioned in 1 Peter. It describes Christ being greeted joyfully by the righteous who had been waiting for the day of his triumph over death. But the focus of the story is on Jesus’ concern for the unjust, who also awaited their fate, and on how he chose “from among the righteous . . . messengers, clothed with power and authority, and commissioned them to go forth and carry the light of the gospel to them that were in darkness, even to all the spirits of men; and thus was the gospel preached to the dead.” This passage clearly relates to the Saints’ sense of duty to prepare for the possibility that some will accept the gospel after death. But more significantly, for believing readers D&C 138’s elaboration on 1 Peter satisfies questions about God’s justice in a world where few have known of Jesus and many are so burdened by temporal cares that they cannot hear his message. Ultimately, these two sections of the D&C, coupled with the expanded canon’s expansive view of the scope of the atonement and the power of Christ’s resurrection, are a source of great personal assurance to the Saints about everyone’s destiny because God’s saving work is ongoing.

Each year in a repeating four-year cycle, one of these canonical texts is the subject of the LDS Church’s Sunday school curriculum for youth and adults. Members are expected to read the designated scripture from beginning to end. Each book of scripture is considered as essential as any other, though the Bible is given two years of this cycle, one for each testament. The Book of Moses and the Book of Abraham are treated seamlessly within the Old Testament curriculum, as was done the day my friend brought his coworker friend to class. There is no canon within a canon—only a single history of God’s efforts to be heard in all places and by every generation.

Mormons are not theologians or even particularly doctrinaire; they are primarily narrativists. They inhabit the world of the book. They read themselves into the salvation history it tells and orient themselves to the horizon created by its promises. In sum, Latter-day Saint scriptures play a definitive role in the lives of believing readers, informing them of who they are in relation to God, why they are here and where it is possible for them and their loved ones to go. In respect to this world and the next, the Saints’ scriptures give them a distinctively positive sense of human potential based on God’s capacity and desire to save them and everyone else, as it says in the Book of Mormon, “through the merits, and mercy, and grace of the Holy Messiah.”

From Conciliaria: Back to the Future (of the Liturgy)

The Future of the Liturgy:

Liturgical Week to open at Seattle World’s Fair tonight

Original publication, 20 August 1962, by Seminarian Michael G. Ryan

From Seattle, a report on the upcoming National Liturgical Week by Michael G. Ryan, a seminarian at St. Thomas Seminary in Kenmore, Wash.

This is an exciting time to be in Seattle. I never imagined that our city would host a World’s Fair, but now the “Space Needle,” as they are calling it, rises at the foot of Queen Anne Hill, and the sprawling modern buildings of Century 21 have taken the place of the quiet neighborhood where my dad once taught me to drive. For Catholics, it is an especially exciting time, since Seattle will also be hosting the National Liturgical Week from August 20 to 23 at the World’s Fair Arena.

The Century 21 exhibits are all about the future—there are displays about Sputnik, space exploration and new inventions (including telephones with push-button pads instead of dials – amazing!). But good as these inventions are, we know that this endless advancement is not the purpose of life. Our Archdiocesan newspaper, the Catholic Northwest Progress, reports:

We Christians are not indifferent to these works of human genius. We too are thrilled to find ourselves now at the very threshold of untold new worlds. But in all this we must be reminded again that our eternal hope lies still not in any works of man’s doing, but in the ageless Victory of the Risen Christ: in the triumph of Life over death.

We live always in the “last days,” preparing for no other future than the Coming of Our Lord and the lasting triumph of His Kingdom. These truths, which are the constant theme of the liturgy throughout the year, will be developed in the major talks of this Liturgical Week and will be applied to our practical Christian living. (April 13, 1962)

It is fitting, then, that the theme chosen for Seattle’s Liturgical Week is “Thy Kingdom Come: Christian Hope in the Modern World.”

What is a Liturgical Week?

The first Liturgical Week, sponsored by the National Liturgical Conference, was held in 1940, in a room in the basement of Holy Name Cathedral in Chicago. It was attended by just a handful of people, mainly priests. But these days, it is clear that the Liturgical Movement is not just a fad or a trend, nor is it only for priests. Pope Pius XII, and his successor, our beloved Pope John XXIII, have embraced the Liturgical Movement as the work of the Church itself. Last year’s Liturgical Week in Oklahoma City drew about 5,000 people–priests, religious, and laity–who came together to pray together and to learn more about the Church’s worship and to explore displays, listen to lectures, view demonstrations and art exhibits, and even take part in a contest for the best church design. This year’s Liturgical Week in Seattle is expected to be the largest yet, with as many as 6,000 participants. The added attraction of the World’s Fair, and the excitement about the forthcoming Ecumenical Council, both have something to do with the surge of interest in the Liturgical Week.

Feverish Preparations Underway

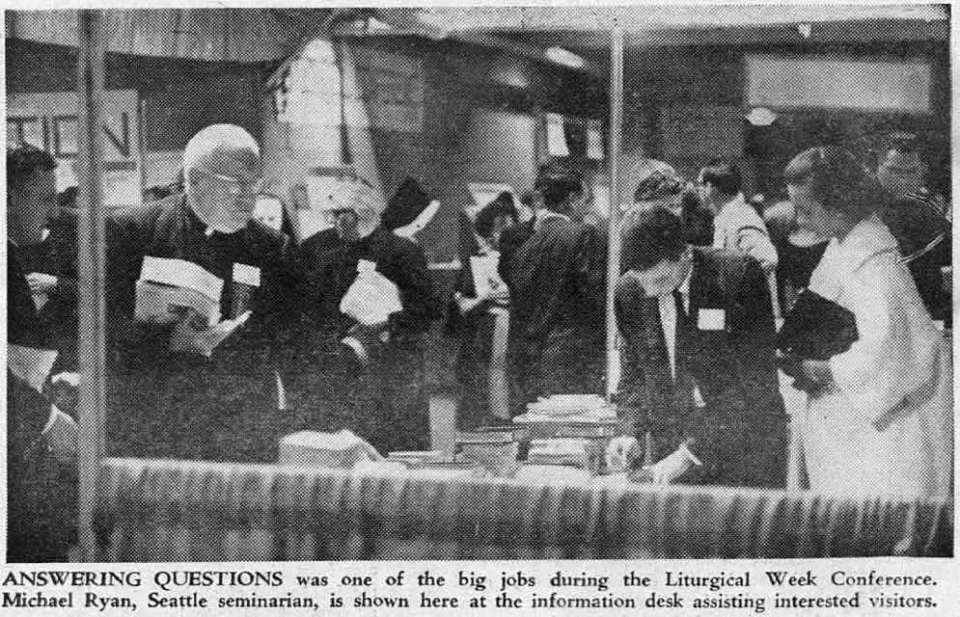

All of us seminarians are glad the Liturgical Week is happening in August, because it means we are free to join in these exciting events. Most of us are helping out in some capacity or other, as it will take hundreds of volunteers to pull together this three-day event. There are dozens of drivers to bring special guests to and from the events. Others are forming a typing pool during the conference. About a hundred men and women will join in a National Choir. And then dozens of volunteers are needed as ushers and greeters at all the events.

I have been assigned to host some of the guest priests in the mornings, and then to help at the information desk at the Arena in the afternoons. One of my seminarian classmates and I will be responsible for preparing for the priests’ morning Masses at the temporary altars which will be set up in lower level of the Mayflower Hotel downtown. It should be pretty exciting for us to serve the Masses of these liturgical luminaries whose names we have seen on the covers of books, but whom we never dreamed we would meet in person: Father Frederick McManus, the President of the Liturgical Conference, Father Gerard Sloyan of the Catholic University of America, and Father Godfrey Diekmann, OSB, from St. John’s Abbey in Collegeville, to name just a few.

Arranging facilities for Masses has occupied much of the energies of the organizers, since about 300 priests will be participating in the Liturgical Week and each of them needs an altar to celebrate his Mass each morning. About 100 of them will be saying their Masses at St. James Cathedral, where in addition to the Cathedral’s altars, temporary altars have been set up in the Cathedral Hall. There are also about 28 prelates in attendance, and Father James Mallahan, the Seattle priest in charge of local arrangements, has had the large task of borrowing 28 prie-dieus from neighboring parishes and chapels, and returning them again when the Liturgical Week is over.

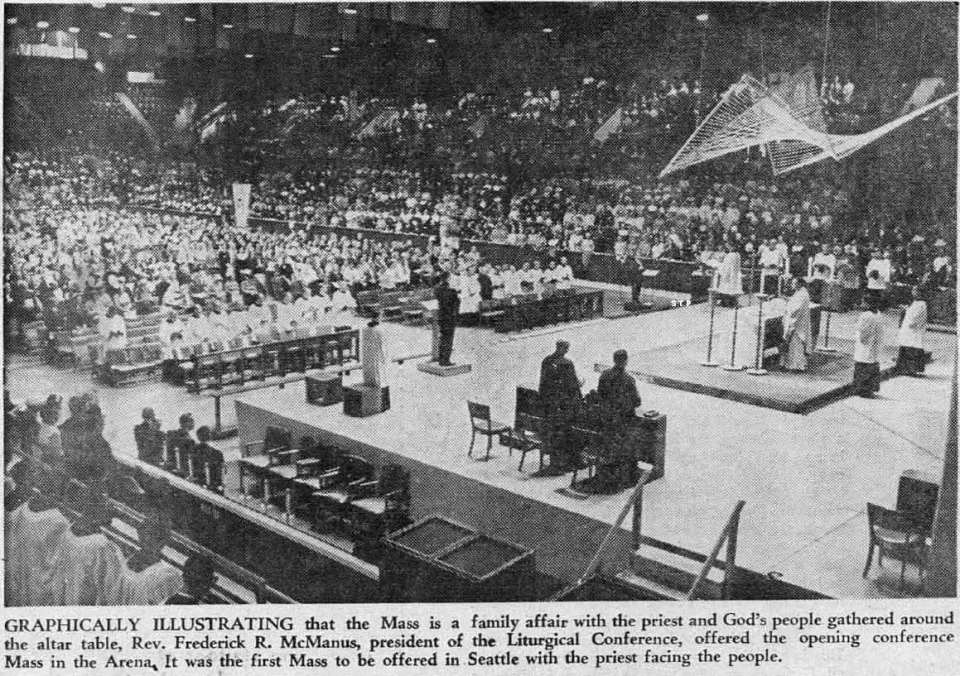

It all begins tonight, with Mass at 5:00 p.m., celebrated by Father Fred McManus. It will be in Latin, of course, but there is a lot of talking and dreaming about a vernacular liturgy among the members of the Conference – even though one of our seminary professors told us recently that such a thing would never happen in our lifetime.

A first for Seattle, and most people present: Mass in the ancient form, facing the altar and the people.

But there will be one very noticeable change at the Conference Masses in the Arena: through a special indult from Rome, all of them will be celebrated facing the people! I wonder what that will be like. I’m especially wondering what it will be like at the concluding Mass when Archbishop Connolly is scheduled to be the celebrant. I’m not sure he is completely favorable to all the latest liturgical developments (which are really not new at all but far more ancient than what we have grown up with), but I suspect he’ll be a good sport and do his best. One thing is for certain: like the Space Needle and the other exhibits of the World’s Fair, the Liturgical Week promises to give us a glimpse of the future. It’s one I can’t wait to see!

Back to the future: The Very Rev. Michael G. Ryan is pastor of St. James Cathedral, Seattle.

Breaking Bad Liturgical Habits

George Weigel wrote this column in January for ‘the other’ NCR that recently piqued my liturgical antennae.

He has good points and bad, mixed together in an acerbic style that is by now pretty well known. It got me thinking about my own version, offered in contraposition and in complementarity, based especially on some of the “liturgical abuses” I have witnessed in Rome, as well as some of the “best practices”.

It has happened on occasion, even here in Rome, that I have been accused of being a true liturgist – in the sense of the old joke about the difference between terrorists and liturgists. I offer these as suggestions merely, humbly, and invite, as always, critique and commentary.

Some of the basic points I agree with Weigel are these:

“there is no “reform of the reform” to be found in lace surplices, narrow fiddleback chasubles and massive candles.”

Another great sage of liturgical aesthetic, the clock from Disney’s Beauty and the Beast, put it this way: “If it ain’t Baroque, don’t fix it!” We are as done with Baroque as we are with orange shag carpeting and felt banners, thank God. Let us not idealize one period of the past at the expense of the entirety of Tradition, and the need for ongoing aggiornamento. Ecclesia semper purificanda, after all.

“Catholics who embrace the truth of Catholic faith do not enjoy clericalism.”

Clericalism is a systemic and personal sin that ought to be rigorously avoided and rooted out of ecclesial structures like the cancer that it is… but, that is a topic for another post.

“Music directors and pastors: As a general rule, sing all the verses of a processional or recessional hymn.”

Weigel seems to conflate his personal musical taste with some objective sense of quality, and goes on to express this rather rudely and without perspective – Compared to the angelic chorus, even the best of Palestrina, Bach, and Mozart, would sound like a ‘treacly confection’. That aside, this is one way we can remember we have left chronos and entered kairos.

I would just add that songs should be singable, for the most part, though there is room for a reflection or meditative hymn, it would be a tragedy if the entire liturgy were converted into a concert given by professional choirs in polyphonic chant that is impossible to follow without expert training. It is not without reason, and this is one of them, that more than one cardinal expressed to us while visiting Notre Dame that the Triduum liturgy there was done better than in Rome!

“Sacred space [sanctuary] is different from other space; the inside of the church is different from the narthex.”

True… but how many churches do not have adequate narthex space? Most I would say. At St. Brendan the Navigator in Bothell, WA, there is an excellent example of good use of narthex and sanctuary/nave in the same building.

He also offers a few points that I disagree, or would attenuate

“Celebrants (not ‘presiders’)”

Weigel channels Ratzinger when he insists that presider be called celebrant. The problem is simple, though. The entire assembly celebrates the Eucharist, but only the bishop (or presbyter-delegate) presides. This language goes back much further than that of “celebrant”, and we can see the title in Justin Martyr, before presbyters are even allowed to take on the role.

“Extraordinary ministers of the Eucharist are vastly overused in U.S. parishes, a practice that risks of signaling that the Mass is a matter of the self-worshipping community celebrating and feeding itself.”

There may be some parishes where extraordinary ministers of communion are overused, but when I see hundreds upon hundreds of communion ministers at St. Peter’s here in Rome, whether priests, deacons, or extraordinary, it is hard to say that anywhere else overuses them. Most use what they need. And there is no connection between having too many communion ministers and making the mass a self-worshipping act. This is a nonsensical and unsupported assertion.

“no one outside of those in holy orders should “bless” in a liturgical context”

This is a matter under the authority of the local bishop, as legislator and liturgist of his diocese. Offering a blessing at communion, especially to those not in full communion, but who desire it, is a significant practice that should not be lost.

“And while we’re on the subject of the congregation, might we all reconsider our vesture at Sunday Mass?”

Absolutely. The entire assembly, at least those fully initiated with Baptism, Confirmation, and admission to the Eucharist, should be vested in albs, the white baptismal garment. Can you imagine the effect, if all the initiated were actually vested?

Bad habits in Rome

When in Rome, do as I want to do.

The cynical observer, or the realist, will tell you that the Romans do pretty much whatever they want. But when you come to Rome, observe the official practice, and the actual practices, and try not to impose your practice from Milan, Seattle, or London upon the community here. Observe and adapt.

At the same time, just because (some) Romans do it does not make it right. Here are a few observed practices of which I am wary:

Communion from the tabernacle during the liturgy.

The ideal situation is that each Eucharist should consecrate enough bread and wine for all those present, and maybe just enough for the sick and homebound. Ideal is not always pastorally possible. However, here, you can frequently see only one host consecrated, for the presider, and then everyone else served from the tabernacle.

Communion under one kind only.

While minimally sufficient, it should normally be under both species, or it lacks the fullness of the sacramental sign. Further, it is the choice of the communicant to receive on the tongue or in the hand. The latter is more ancient, the former is canonically the norm here in Italy. I have addressed these points here and here.

Confessions during the liturgy.

It is one thing in a giant basilica where you have mass in some side chapel, and confessions going on a football field away in another part of the building. Quite another when the 18th century wooden confessional is cozied up so close to the pews in the parish church that you can hear the penitent while you are sitting in reflective silence after the homily. When the liturgy begins, no other sacrament or devotion should be happening in the sanctuary, unless it is a part of the liturgy.

Many altars, many breads, no body.

One of the beautiful tragedies, or tragically beautiful moments, is if you go to St. Peter’s early in the morning (this happens rarely for me), and you see dozens of priests at dozens of altars all offering the Mass, separately, and with at most one assistant. It is easy to think of all the places in the world where people go days, weeks, or months without access to the Eucharistic liturgy. But it also begs the question, why not concelebrate? Why not have one mass, so that the few morning pilgrims could all join as well? Is a liturgy without the presence of the Church even a liturgy, or a private devotion of the presbyter?

Excessive Concelebrating.

I never thought I would agree with the Lefebvrists on much beyond the basic dogmas of the faith. But they have a certain point here, though for different reasons. Imagine a liturgy with twenty people. Fifteen are vested and concelebrating, and five are in ‘plainclothes’ and simply celebrating. Is it really necessary to have so many concelebrants? A priest may feel obligated to celebrate the Eucharist every day, and this is a worthy thing, but he need not do so vested every time, especially in such a scenario. There could be the presider, a deacon, and as many concelebrants as needed for communion, or for a preacher, etc. With occasional exceptions, less is more.

We stand for prayer, not for announcements.

The most elegant remedy to this I have seen is that the Prayer after Communion be offered at the end of the Communion procession, rather than at the beginning fo the concluding rites. That is, remain standing (or kneeling, or sitting, as the local case may be) for the entire communion procession, and as soon as everyone has received, the presider offers the communion prayer. Only then do we sit in silence (or with meditative hymn) for the post-communion reflection. Then, while still seated, any announcements can be made.

Christmas and Easter.

Midnight Mass is at Midnight. Not 10pm. Even if the pope does it. Then, you can still use the midnight readings, just do not call it midnight mass! At Easter, do not do as the Romans did last year…. At the Vigil, the lights came on entirely too early. Actually overheard behind me “Well, that rather destroys the effect, doesn’t it?” or variations, from more than one voice. Let the service of light continue as long as it can, the readings can mostly be done in darkness, with only the paschal candle to light the ambo.

Assisi in August

Though I usually try to spend the night, a visiting friend and I made a day trip to Assisi. I have been there in all seasons but the height of summer, until now. By now, I have reported on all the major sites, and mentioned before my favorite little church, essentially untouched in its 900 year history, Santo Stefano.

Though I usually try to spend the night, a visiting friend and I made a day trip to Assisi. I have been there in all seasons but the height of summer, until now. By now, I have reported on all the major sites, and mentioned before my favorite little church, essentially untouched in its 900 year history, Santo Stefano.

The diocese is currently planning the church’s (purportedly) first-ever renovation, but it was not clear what that would entail. Hopefully, nothing baroque!

As we approached, we saw a small sign inviting us into the adjacent monastery garden for rest and refreshment. On entering we found a small group of pilgrims from northern Germany who were in town with a total of about 20 from their parish, including the pastor, who were spending a few weeks in Assisi offering this simple hospitality ministry in shifts. Shade, water, and greenery with a view was a most welcome respite in the heat of the day (though much cooler than Rome, at 30C/85F it was still hot!).

Apparently this is the second year of these groups coming to live a few weeks in Assisi and offer the ministry to pilgrims and tourists. I wonder if they take Americans?

PEW Study: Catholics More Satisfied with Leadership of Religious Sisters than of American Bishops

An interesting report from the Pew Forum, and comments from a Franciscan blogger in D.C., who i met in Assisi…

McDonalds, Chick-Fil-A, and Voltaire

This picture came across Facebook, which is where I have been getting most of my US news that for some reason does not seem headline worthy internationally… like the whole Chick-Fil-A thing. Of which, honestly, I know little, and did not want to go researching too deeply. For all i know, this was photoshopped. Or, it could be the opinion of a local franchise manager and not corporate HQ.

But there’s still a timely lesson there, so I reposted with my favorite quote from Voltaire,

“I may disagree with what you have to say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.”

So, is McDonalds saying they agree politically with Chick-fil-A? Or simply asserting their support for a corporation to act according to the principles and values of its ownership? Personally, I have never been to a Chick-Fil-A, they just do not exist in my part of the country, and I have rarely been to a McDonalds in the last decade.

Not knowing much about the original controversy, I could not say whether I agree with Chick-Fil-A or its critics, both, or neither.

I can say that I support both companies in this: they are not the government, and therefore they have the right to be religious or not religious, to run their company according to Christian, Muslim, Jewish, or secular humanist principles as they see fit. There is no law that says a privately held or publicly traded company must maintain a wall of separation between church and boardroom – or rather that even if there is a distinction between the two, it is not the case that the one has no business influencing the other’s business.

I would especially applaud McDonalds if they disagreed with Chick-Fil-A politically, but supported them anyway, with their right to run their business according to principles. Then they would be in the place of Voltaire, ironically reminding us all of the need for a little civility in civil discourse and political disagreement! Also a reminder that religious freedom is not eclipsed at the doorway to the church, synagogue, or mosque; it extends to the public sphere, and even into the corporate offices of fast food restaurants.

A couple more relevant facebook-shared images:

Lord I am not worthy…

English masses in Rome after the translation

“Lord, I am not worthy that you should enter my table… roof… whatever…”

I actually heard these words at a liturgy a few months ago. Some of the changed language has caught on beautifully: “Right and Just!” and “..and with your spirit!” were a little easier for everyone here to adopt, since these are in the Italian translation as well.

Because the Italians are not worthy to welcome the Lord at their table, rather than under the roof, however, and every language seems to have translated, rather than transliterated, this idiom previously, there are places where this one is not yet been received. Likewise, the Creed and the Gloria tend to still require the use of the convenient cheat-sheets included now in every church, but often enough, it will be the old Gloria, and an occasionally mumbled Creed.

Of course, it depends where you go. At the NAC-lead English station masses during Lent, you would never know there had been any other way to celebrate the mass. Each of the national colleges or parishes has their own quirks and adaptations, and the international English-language community, with regular worshipers from over twenty countries, probably gets the most variety.

In December, I was preparing for an evening liturgy in one of the Roman basilicas, as the rector proudly showed me the new English-language Roman Missal they had just purchased, our group being the first to use it. So concerned with navigating it, as it was my first use of it as well, I failed to notice the Lectionary was still the 1970 version…

Even in Rome, the biggest contingent of anglophones are those who were, shall we say, less than enthusiastic about the new translations. The second largest would be those who prefer we dump the translations entirely and stick to the Latin and Greek. Already there are rumors about the need for revisions…

Look West, Young Church!

For the last several decades, the US Catholic Church has been demographically shifting from the 19th century bulwarks of New England and the upper Midwest, to the South and the West.

That does not mean that fact is quickly grasped by individuals or institutions. At one national conference I attended annually for nearly a decade, it was clear that the organizers thought of it as a nation-wide event. Yet, in its 45+ year history, only two had been held in the Northwest, both in the ‘80s; fewer than ¼ of the meetings had been held in the western half of the U.S.

Or consider that of nine cardinalatial sees in the U.S., seven are east of the Mississippi. And one of those that is west of the mighty river, Galveston-Houston, is so close as to still be part of the eastern half of the mainland U.S.

This is not as bad as the need to redraw diocesan boundaries in Ireland, which have been unchanged for just over 900 years, yet it is still slow… But, I digress…

Recent moves indicate that Seattle is making its mark felt again on the national, and international, ecclesiastical scene. Not since the days of Archbishop Hunthausen has the Church in Western Washington captured attention much beyond its own boundaries.

Recent moves indicate that Seattle is making its mark felt again on the national, and international, ecclesiastical scene. Not since the days of Archbishop Hunthausen has the Church in Western Washington captured attention much beyond its own boundaries.

Fast-forward a quarter of a century, and for the most part Seattle had dropped off the radar, but not gone silent. Just in the years since Archbishop Murphy took over from Archbishop Hunthausen, the Catholic population has nearly tripled due to immigration – now there are as many Spanish-speaking Catholics in western Washington as there were total Catholics 15 years ago. Bishop George of Helena, Bishop Joseph of Yakima, and Auxiliary Bishop Eusebio have all been ordained from the local presbyterate, the first such ordinations in nearly half a century.

The reputation of being on the cutting edge of lay involvement and creative pastoral ministry solutions, social justice and ecumenical commitment has slipped in recent decades, both among those who cheer the change and those who lament it. My age-peers in the presbyterate are as likely to be interested in the traditionalist movement and the extraordinary form as their peers anywhere else in the country, and some of the most well known Catholic voices to have come out of the Seattle milieu – author George Weigel and blogger Mark Shea – are not known for their particularly progressive mien.

Consider, though a few highlights of the last few years that suggest that there is attention shifting back towards the Emerald City and her local Church – both Catholic and Ecumenical. Some of these are newsworthy enough to get attention here, across the atlantic, so they certainly say something is happening. Significantly, you cannot pigeonhole all of these into “progressive” or “conservative” success stories, but nevertheless indicate that, perhaps, Seattle is on the radar again.

By now virtually everyone knows some part of the liturgy wars saga. Most people do not know it all; I certainly make no claim to such comprehensive view of the last fifty years of liturgical reform, renewal, development, reform of the reform and rejection of reform.

To recap the most recent, let us say that the updated translation everyone was waiting on was ready and fully approved by episcopal conferences around the globe in 1999. It then got delayed as a new Prefect of the congregation for divine worship rewrote the guidelines for liturgical translation, and the entire process was started anew with new rules and much controversy – and it was done quickly. After only a decade, the implementation was looming.

Enter the Very Reverend Michael G. Ryan, pastor of the Cathedral parish of St. James, where he has served as quite possibly the city’s most popular Catholic pastor since 1988. In December 2009 he penned an article for America asking the question, “What if we just said, ‘wait’?” , and launched a website gathering signatures and comments. In short order over 23,000 people signed – and a counter movement was launched. “We’ve waited long enough!” collected just over 5,000 signatures and practically launched the blogging notoriety of “Fr. Z” and his (proudly) rubricist blog, What Does the Prayer Really Say?… and it all started with the quintessential Seattle presbyter, Fr. Michael.

Just the other day I was at the retirement party for the superior general of one of the religious orders, and conversation turned to Fr. Ryan’s stand and his recent article, “What’s Next?” Naturally, the group included supporters and critics alike, but several who were neither from the west coast or the U.S. at all – this is news throughout the Anglophone world.

In the three years since, coterminous with my time in Rome, there have been other indicators. Some smaller – like the meeting of the National Catholic Melkite Convention there in summer 2010 and the scheduling of the upcoming conference of the Society for Pentecostal Studies. Some have a bigger profile, like the June 2011 meeting of the USCCB in Bellevue.

In terms of ecumenism and lay ministry, there have been some exciting personnel moves:

In Summer 2011, Dr. Michael Reid Trice was hired at Seattle University as the associate dean of the School of Theology and Ministry. Michael and I have known each other for several years, and he is one of the most active young ecumenists in the country, having served since the age of 35 as the associate director of the ELCA’s ecumenical and interreligious office.

Shortly thereafter, it was announced that Dr. Rick McChord was retiring after 25 years in the USCCB office for laity, marriage and family – and picking up a consulting contract with Seattle-based (and Domer-founded) Reid Group, which specializes in leadership development, strategic planning and mediation for religious groups.

The latest came in April while i was in Assisi, with the retirement of Rev. Dr. Michael Kinnamon as General Secretary of the National Council of Churches, and his own move to a three-year contract at Seattle University, starting this fall.

Finally, the biggest spotlight to hit Seattle in recent years, ecclesially speaking, is the appointment of the relatively new metropolitan, Archbishop J. Peter Sartain, to lead the five-year overhaul of the Leadership Conference of Women Religious. Striking every note of consultation, careful listening, and collaboration a person in his position possibly could during the press conference and interviews later with John Allen in Rome, it seems like the best has been made of an unpleasant situation.

These are exciting times to be in the church-world in Seattle. Almost a pity I am in Rome!