Home » La vita Roma (Page 19)

Category Archives: La vita Roma

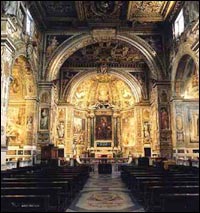

Santa Susanna: the American parish in Rome

With friend and ecumenical mentor Ron Roberson, CSP in town this week for the updating of the Vatican’s official guide on the eastern churches, I decided it was time to make my first visit to the American parish in Rome, Santa Susanna.

Having spent 11 years in Rome as a student at the Oriental Institute and then as staff to the Pontifical Council, Ron also served as vice-rector of the parish community at Santa Susanna, which is staffed by the Paulist fathers. So, on this brief visit back in Rome, he was presiding at the 10:30 liturgy for Christ the King, and it seemed as good a time as any to try it out. I had been ‘warned’ that it was a “typical American parish”, despite my skepticism that such an animal existed.

The church of Santa Susanna is one of the oldest in Rome, originally build in 330 AD in the Constantine basilica style over the house church of St. Susanna, martyred in 293 AD. You can still go down into the crypt, which was part of the original house, and where the Eucharistic feast was celebrated since at least 285 AD. St. Susanna, her father St. Gabinus, and St. Felicity are all buried here.

During the 8th and 16th centuries it went through some dramatic renovations and restorations. The current design and style dates to 1595, and the façade was the original masterpiece of Carlo Maderno, whose work impressed Pope Sixtus V enough that he was commissioned to do the same for St. Peter’s Basilica.

The liturgy and community experience was, I admit it, ‘typically’ American, especially compared to my other liturgical experiences of the last two months. The organ played too loudly, so you could hardly hear the choir or assembly sing. The music was otherwise good, generally singable, and very mixed in style. The preaching and presiding were great, not surprisingly. There was even a full 8 ½ x 11 parish bulletin (most Roman churches have none, or a smaller worship aid rather than announcements), and coffee and cornetti after mass in the vestibule.

People always ask about liturgical postures, so I have to add that the most notable was how much time was spent kneeling: More than any other church in Rome, including the Tridentine rite parish! The universal norm calls for standing throughout the Eucharistic prayer, but several national churches have adapted that somewhat to include kneeling. In Rome, either you stand the whole time (as at the papal liturgies) or just kneel between the Epiclesis and the mysterium fidei. The U.S. norm is kneeling from the Sanctus to the Great Amen – which seemed like a really long time compared to the Roman practice. Then, they knelt for the communion rite too, which I have not seen in Rome, or in the States since before the GIRM revisions.

Thankfully, in proper American tradition, we had padded kneelers.

Ecumenical Vespers at “del Caravita”

The Oratory of Saint Francis Xavier “del Caravita” is one of those churches in Rome you would never find unless you knew where to look, even though it is just off one of the main thoroughfares in the City. It is described as “an international catholic community in Rome”, Jesuit in origin but staffed by priests from four different orders. Aside from the national churches for the U.S., England, Ireland, and the Philippines it is the only Catholic church offering weekly Sunday liturgy in English.

On Friday, we celebrated evening prayer presided by Cardinal Kasper, with Archbishop Rowan Williams as the homilist, sponsored by the Anglican Centre in Rome. A simple and beautiful liturgy with what I thought was an especially powerful version of the renewal of baptismal vows, it was a nice counterbalance to the Colloquium the day before: a day of academic lecture complemented by an evening of prayer.

The pack of news photographers that had followed Dr. Williams throughout the lectures yesterday was back tonight, and it amazes me he was able to focus on preaching with the constant picture taking. Of course, trying to find one of these photos online to share is not easy, this is the best I could do: http://www.catholicpressphoto.com/servizi/2009-11-20%20Vespri/default.htm

After the prayer, we were able to meet the Cardinal, the Archbishop, and even U.S. Ambassador Miguel Diaz and his wife, Marian, who were in attendance. Unfortunately, we only got a couple shots with Archbishop Williams, though I did invite Cardinal Kasper to dine at the Lay Centre sometime. (We’re on the Ambassador’s list already. Somewhere down there…)

Jan Cardinal Willebrands, 1909-2006

Johannes Cardinal Willebrands would have celebrated his 100th birthday this fall, and Rome honored this great ecumenist, bishop, and Council father with a day-long Colloquium hosted by the Pontifical Gregorian University.

Cardinal Willebrands was bishop of Utrecht in his native Netherlands, and served for twenty years as the second president of the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity, from 1969-1989, succeeding Cardinal Agustin Bea with whom he had worked closely during the Council.

Seven lectures traced the contributions of Cardinal Willebrands to the Church and the churches, each about half an hour, interspersed with Q & A time and the obligatory pausa for caffè and pranzo:

- William Henn, OFM: Cardinal Willebrands and the relations between Rome and the Ecumenical Council of the Church

- Michel Van Parys, OSB: Cardinal Willebrands and ecumenical relations with the Churches of the East

- James Puglisi, SA: Cardinal Willebrands and ecumenical relations with the Churches and Ecclesial Communities of the West

- Msgr. Pier Francesco Fumagalli: Cardinal Willebrands and the Jews

- Archbishop Rowan Williams of Canterbury: An Ecumenical Testimony

- Jared Wicks, SJ: Cardinal Willebrands and the development of Catholic ecumenical theology

- Cardinal Walter Kasper: The heritage of Cardinal Willebrands and the future of ecumenism

Unfortunately, the Holy Father’s general audience for the students of the Roman universities was scheduled during the morning, so several students opted for that instead, but the ecumenical section of the Angelicum was here almost in full!

While the morning helped paint a vivid picture of the life and many contributions of Willebrands to the Catholic Church and its commitment to ecumenism, the afternoon focused as much on the current and future situations, and made several references to Cardinal Kasper’s new book, Harvesting the Fruits: Basic Aspects of Christian Faith in Ecumenical Dialogue.

When some people lament the apparent ‘slowing’ of ecumenical progress in the last twenty years, as compared to the previous thirty, the golden age remembered is the period in which Willebrands was either President or Secretary of the Council for Promoting Christian Unity (named the Secretariat for Christian Unity when first established).

Cardinal Kasper has described him this way:

“He had many qualities: sensitivity and discernment in judging people and situations; great capacity to communicate; the gift of nurturing true friendships. All this is fundamental for ecumenical dialogue since ecumenism means overcoming suspicion, building trust and creating friendships. In Willebrands we find the right balance between a passionate eagerness for unity and that patience which does not try to force things but lets them grow and mature. Not least, Willebrands had an exceptionally fine sense of humour, humour being often the only way to face small-minded and sheepish attitudes.”

Before the Council, when Catholics could not attend ecumenical meetings or participate in ecumenical prayer, Willebrands and others would faithfully observe the letter of the law, then accept invitations to tea with a group of sisters who would also, coincidentally, invite the members of whatever commission or meeting was going on in ecumenical circles. In this way early Catholic contributions were not lost to the ecumenical conversations, and the beginnings of a network of friendships was being developed. It was a way of being “obedient to the Church, and more obedient to the will of Christ”.

Willebrands established a “Catholic Conference for Ecumenical Questions” in 1951, to discuss Catholic issues ‘in response to’ some ecumenical initiatives. This was done while maintaining open contact with Cardinal Ottaviani in the Holy Office (the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith). He was instrumental in arranging the meeting between Pope Paul VI and Patriarch Athenagoras in which the mutual excommunications of 1054 were renounced. He helped establish the Joint Working Group of the World Council of Churches and the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity, and was the primary point of contact between the WCC and the Catholic Church for decades.

During the Council, Willebrands was able to use the previous decade of personal relationships to draw up a list of ecumenical observers to be invited, and was their host throughout the Council. These observers and staff of the secretariat would meet weekly at the Centro Pro Unione on Thursdays, to get a debriefing of the week’s interventions (which were in Latin) in English and other more common languages. Often there would be a presentation by one or more of the peritii of the council. As the bishops themselves heard about these gatherings more and more would attend, at the least to hear in an understandable language what had been discussed in front of them the week previous!

Near retirement, Willebrands noted that the best ecumenists have been theologians, but also that “ecumenism is first a way of being Christian, before it is a theological or pastoral competence.” He published, in 1987, an article titled “Subsistit in”, Vatican’s Ecclesiology of Communion, which is one of the most authoritative interpretations of the nature of the church in Lumen Gentium 8, along with the work of Joseph Ratzinger and Walter Kasper.

One of the last reflections he gave in Rome before retiring to the Netherlands was at the invitation of the Lay Centre at Foyer Unitas, and delivered in the Centro Pro Unione, “Why I Am a Man of Hope” – a summation of all his experience and why he maintained hope for the future of the Church and ecumenism.

Archbishop Rowan Williams of Canterbury

In reading some of the headlines the next day, you might have thought that the entire colloquium was just a platform from which the Archbishop of Canterbury could fling the gauntlet at Benedict’s feet on the issue of the ordination of women. This was not the case, and the issue of ordination was raised as an case in the broader question of the relationship between local and universal church, and the theological weight of divisive issues. (His entire address is here.)

Rather, it was a time for him to assert that he too, was a man of hope for the future of the ecumenical imperative, while acknowledging some hard questions that need to be asked, the central question being,

“…whether and how we can properly tell the difference between ‘second order’ and ‘first order’ issues. When so very much agreement has been firmly established in first-order matters about the identity and mission of the Church, is it really justifiable to treat other issues as equally vital for its health and integrity?”

In other words, given the depth of our agreement on the nature and mission of the church, on Baptism and Eucharist, et cetera, do the remaining issues of division – such as the understanding of authority, primacy and the relationship of local to universal church – carry the same weight as the issues that unite us? These are questions pertaining to the hierarchy of truths, and asked by our fellow Christians who desire unity:

“All I have been attempting to say here is that the ecumenical glass is genuinely half-full – and then to ask about the character of the unfinished business between us. For many of us who are not Roman Catholics, the question we want to put, in a grateful and fraternal spirit, is whether this unfinished business is as fundamentally church-dividing as our Roman Catholic friends generally assume and maintain. And if it isn’t, can we all allow ourselves to be challenged to address the outstanding issues with the same methodological assumptions and the same overall spiritual and sacramental vision that has brought us thus far?”

The Church of Rome

Every Wednesday brings a guest presider with a normally brief presentation during and after dinner. This week was an opportunity to get a better look at the Church of Rome, from some excellent authorities.

Our presider was Don Nicola Filippi, ordained a presbyter of the diocese of Rome in 1995 and named a Chaplain of His Holiness (the lowest grade entitled “Monsignor”) in 2005, he serves as secretary to the Cardinal-Vicar of Rome, Agostino Vallini. Princess Gesine and her husband, Deacon Masimilliano, of the Doria Pamphilj family, joined us as well. Don Masimilliano and Donna Gesine are friends of the Lay Centre and were our generous guides when we visited the family palazzo/galleria last month.

Vested for the liturgy, Don Nicola is the very image of a classical Roman senator, and I think will be a bishop himself in the next decade. Two interesting liturgical observations: there are very few deacons in Italy, I think Masimilliano is one of only two in the suburbicarian diocese where he is incardinated, so it was clear there is room for a more robust development of their role. Also, since communion under both species is not as common in Italy as it is most places in Europe and North America, Monsignor Filippi chose to serve communion by intinction, I think as a kind of pastoral compromise between his custom and ours, which was a first for me.

The Church of Rome, the diocese itself, is an interesting reality. Their diocesan bishop is the pope, and yet, as Father Nicola said, “Rome is Rome, and the Vatican is something else entirely. That’s the other side of the Tiber.” Some of the pastoral and administrative issues sound not all that different from home!.

There are about 2.5 million Catholics in the diocese of Rome, and it includes 330 parishes, plus the other 600 or so churches, which are chapels, stations, oratories, or shrines. Though the bishop of Rome is Benedict, Cardinal-Vicar Villani is the ordinary for almost all intents and purposes. He is assisted by seven active auxiliary bishops, one as a kind of vicar general to the Cardinal-Vicar (who is technically the vicar general), five lead regional vicariates, and one is responsible for hospital ministry. The diocesan website lists 1215 diocesan clergy, 1917 clergy from other dioceses, 4800 religious clergy, 124 opus dei clergy, 2050 lay religious, and 1050 lay staff*. (These numbers include retired clergy, I think, and the website also counted all the cardinals, and over 1200 bishops who are probably curial staff and diplomats.)

Compare that to Seattle, with 578,000 Catholics, including 3 bishops, 294 diocesan clergy, 32 clergy from other dioceses, 96 religious clergy, 486 lay religious, about 800 lay ecclesial ministers and 1393 lay teachers. Rome has less than 5 times as many Catholics, but more than 21 times as many clergy, and half as many lay staff*.

*Lay staff listed for Rome included faculty of the pontifical universities, members of commissions and consultors to dicasteries, as well as actual paid staff in Roman offices – virtually no lay ecclesial ministers as we know them in the States.

Only about 40%-50% of the children born in Rome are recorded as being baptized, and there are only about 80 or 90 catechumens each year, though Fr. Nicola indicated that a large number of families may take their children outside the city, and thus to other dioceses, for baptism so it may not be quite as low as that looks.

He spoke about a questionnaire the chancery had been trying to get parishes to fill out regarding pastoral planning, evangelization and sacramental life, and only about 2/3 of parishes responded (I thought this was pretty good, actually). When the Cardinal started visiting pastors who had not sent the response in, one of the first said, “oh, yeah, we forgot about that. I’m sure it’s here somewhere…” and then proceeded to produce the previous year’s questionnaire, still in the original envelope.

As I am sure you have heard, though Italy is nominally 90% Catholic, very few people are very active in the life of the church. For most, it is where you go to get baptized, married, and buried. Just last night a classmate was telling me how, on his first Christmas in Rome, he attended a popular parish nearby and could not find a seat 20 minutes before mass began, and the church was filled with young people. But then, as the opening hymn began, mobile phones came out of pockets to take pictures and he heard several people calling their mothers, “yes, mama, I’m going to church. See, I’m sending you a picture!” Then they left. By the time of the opening prayer, my friend had no problem finding a seat.

One of the responses that has been very popular in Italy, and in Rome especially, are the lay movements. Whereas the U.S. has seen a greater development in the area of parish life and in lay ecclesial ministry, here there is almost the sense that if you are really serious about your faith you do not go to your parish but spend your time with the movement. Two of the largest in Rome are the Charismatic movement and the Neochatechumenate Way. (I would have guessed Sant’Egidio, Focolare, or Communione e Liberazione).

Unfortunately, some of the biggest problems for the Catholic Church of Rome come from these movements. Poor catechesis, insufficient theological education of the clergy, and the creation of a parallel church to the diocesan-parish structures were all cited as serious issues among the diocesan leadership. The dichotomy of spirituality and theology, so typical of the “classical” western Latin tradition, is noted especially in the Neocatechumate Way with an emphasis on the spiritual and too little attention on the theological. They are also having a challenge with the high number of non-Italian priests coming to serve the communities here, without adequate cultural formation and preparation for the life of the Church in Rome.

This was one more reminder of how slowly my Italian is coming, too, so prayers for that please! I would like to have asked about lay ecclesial ministry in Rome. Next time!

Extraordinary Form: The Tridentine Rite in Rome

With something like 900 churches, chapels, and oratories in Rome, I could visit one a day and still have a long way to go by the time I graduated. However, since we have our community Eucharist weekly in the Lay Centre, I am trying to spend Sunday worship somewhere different each week to continue getting a sense of the Church, both Roman and catholic.

This Sunday I joined some friends who are regulars at the parish church of Santissima Trinità dei Pellegrini (Most Holy Trinity of Pilgrims). Trinità is the personal parish in Rome for the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite, more commonly called the Tridentine Rite. It is staffed by the Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter.

Just as the liturgy was renewed in 1970 by Paul VI in accordance with the Vatican II Council, so it was after the Council of Trent when Pius V promulgated the Roman Missal of 1570. “Tridentine” simply means “of Trent”. The latest of several revisions to this liturgy of Trent was made by John XXIII in 1962, and it is that version which was approved by Benedict XVI on 7.7.07 for use as the extraordinary form of the liturgy.

At one level, I was not sure what to expect. I am too young not only to have missed being formed by this liturgy and the concomitant devotions and ‘Catholic ghetto’ identity, but I also missed the most tumultuous years of peri- and post-Conciliar development, changes, and even occasional abuses. I simply do not have a neuralgic response to either the Tridentine liturgy or to the phrase “Spirit of Vatican II” as do so many of my older colleagues of different generations. Some experiences I have had did lead to some expectations, some of which were confirmed and some of which were totally blown away.

While this was my first experience with a “high mass” according to the extraordinary form, it was neither my first Tridentine nor Latin liturgy. While I have participated in some beautiful liturgies in Latin before, they were all according to the normative Roman Rite – in other words, the same mass we celebrate every Sunday in English, Spanish, Italian, etc.

My (admittedly few) previous experiences of the Tridentine form could not be described, by any stretch of the imagination, as beautiful. In fact, they could hardly be described as liturgy: terrible music, if any, nothing resembling “full, conscious, and active participation” by the assembly, and a vapidity so pervasive that the sacramentality, spirituality, and genuine reverence for the Eucharistic liturgy was almost totally lost. In at least one case the priest’s Latin was so bad the actual validity of the consecration was called into question. Each time it seemed more about making a ‘political’ statement in the culture wars than in actual worship or an act of communion.

Given the people who invited me, however, I was confident that this would not be a repeat of those experiences, whatever it turned out to be. As it turned out, that involved both beauty and illumination.

Gregorian and other chant done well – the music was beautiful. My rusty Latin was enough to know what part of the mass I was in, and to sing along with some of the mass parts, but mostly it was enough to just listen.

About one hundred twenty people were there, the median age seeming to be in their early 50’s, with a pretty good mix from two or three small children to people old enough to have been formed in this rite. We had a crowd of about fifteen students from the pontifical universities, most of whom are regulars. I only saw a couple of mantillas in the whole assembly. A small pamphlet had the readings and some prayers in Latin and Italian. The major parts of the mass were recognizable from the current form of the Rite, and from what I remember studying in my Liturgical history courses. Announcements and collections are not much different, though the former came in the middle of mass rather than at the beginning or the end.

Having an inaudible Eucharistic canon and to be so far removed from the altar did distract a little from prayer and participation, as did not always knowing when to kneel, stand, or sit or precisely why. Not that I could kneel anyway, there was not room enough! One thing that was consistent with more than a few regular parishes, though, was that everybody seemed to have their own expectations about this anyway, and most of the time about half were kneeling while half were standing. It was not very uniform, but neither did that seem to matter to anyone.

Cognitively, I know that the idea of the long nave with a high altar at one end, the presider and other ministers facing ad orientem along with the people is supposed to represent the presbyter leading the people in the sacrifice and their pilgrim journey. I also know that most people experienced this more as a sense of removal and non-participation, of the mass as a private devotion of the priest “over there” while we did our thing “over here”. Personally, it felt neither like I was being led in worship, nor that I was completely removed from the action. As something both deeply familiar and existentially unfamiliar, I guess I was in more of an observer-participant role, a student in prayer.

The need for the renewal and reform of Vatican II was made evident to me, on one hand. This is a liturgy pretty far removed from those described in the early church, and not easily accessible for a lot of people, especially if not done as well as it was at Trinità. On the other hand, I could see how it would be a difficult adjustment for people formed by this liturgy to adapt to the current Rite, especially if their experience of the transition was handled badly and without proper catechesis, as seemed to be the case in too many places.

What is most striking to me is the people and their attitude regarding the liturgy, at least those I spoke with, which includes friends from the Angelicum, the Lay Centre, and others. A German friend describes the participants as “traditionalists, but not necessarily conservatives.”

In the States, generally, it seems that the Tridentine mass has become little more than a weapon of the culture war, as I mentioned above. “More Catholic than Benedict XVI, more conservative than Pius IX, and holier than Mother Teresa” would be the motto. Probably they are here too, just as the opposite extreme can be found in some other parishes, if one looks hard enough.

Here, instead, are people of prayer, less interested in proving that they have the “true mass”, than in worshiping as fully as they are able, in a Rite and a spirituality that speaks most clearly to them. Motivated by genine reverence rather than triumphalism, tradition rather than traditionalism, i felt as welcome here as i have my first time in any parish (well, except Blessed Teresa, but that was a truly exceptional experience!)

Dr. Rick Gaillardetz and Archdeacon Johnathan Boardman

Author of seven pastoral booklets, eight books, and over 100 journal articles, Dr. Richard R. Gaillardetz is one of the most accomplished U.S. ecclesiologists of the current generation. He has been a member of the U.S. Catholic-Methodist dialogue, and his doctoral director was Dominican Father Thomas O’Meara at Notre Dame (who was also my systematics and ecclesiology professor as an undergrad). Rick is married, with four children, and currently serving as the Murray/Bacik Professor of Catholic Studies at the University of Toledo (Ohio, not Spain).

Author of seven pastoral booklets, eight books, and over 100 journal articles, Dr. Richard R. Gaillardetz is one of the most accomplished U.S. ecclesiologists of the current generation. He has been a member of the U.S. Catholic-Methodist dialogue, and his doctoral director was Dominican Father Thomas O’Meara at Notre Dame (who was also my systematics and ecclesiology professor as an undergrad). Rick is married, with four children, and currently serving as the Murray/Bacik Professor of Catholic Studies at the University of Toledo (Ohio, not Spain).

The Venerable Jonathan Boardman is an Anglican presbyter, rector (pastor) of All Saints parish in Rome, and Archdeacon of Italy and Malta for the Anglican diocese of Gibraltar, which covers all of continental Europe.

[An archdeacon in the Anglican Communion, as it once was in the Catholic Church, is basically the vicar general, and in this case one of several where each is assigned a geographic portion of a diocese. Though traditionally this was a role for a deacon, the eventual usurping of all diaconal ministries into the presbyterate included this high office.]

Having either one of these men as guests for dinner and conversation over tea would have been a treat, especially now in the wake of the apostolic constitution Anglicanorum Coetibus. To have both on the same night was a true privilege, especially for an ecumenist/ecclesiologist like me. I would have been happy just to sit back sipping my tea, and listen to them discuss the personal Ordinariates, the history of Anglicans in Rome, and the ecclesiologies of our communions today. Both men are as engaging as they are erudite, though, and welcomed questions and comments from those of us who decided to stay and converse rather than head across town for a party with the other lay students of Rome. (Still working on that bilocation thing)

Professor Gaillardetz has written a great deal in exactly the areas of ecclesiology that interest me, including ecumenism, the diaconate, lay ecclesial ministry and a wide range of other topics. I have no doubt that his work will make a significant contribution to my thesis and dissertation, and it is always a blessing to make a real-life connection with someone whose work informs your own.

Father Jonathan I have met on my two forays to All Saints, first for their dedication feast – the Sunday after the press announcement of the Personal Ordinariates – and for Stian’s debut as Evensong Acolyte Extraordinaire. His comments on the Personal Ordinariates, and his personal openness about his reactions since the first announcement and the subsequent publication of the constitution, were welcome, enlightening, and honest.

[In fact, as i write this, i suddenly realize who it is that Fr. Boardman reminds me of: Bishop Daniel Jenky, CSC! Some similar physical characteristics, spoken style and personality. Good preacher. hmmm….]

“I am not angry about all this… and yet, I’m surprised how angry I was!” probably best describes one of the most common reactions, echoed by Father Boardman while relating an incident where an innocent joke about “competition” [between Catholics and Anglicans] by a Vatican colleague touched a raw nerve.

While both the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Holy See’s own Council for Promoting Christian Unity had little notice before the public announcement, and many Anglicans and Catholics alike have seen this as either “arrogant” or at least “unilateral and insensitive”, some Anglicans have also noted that it is not as if the Anglican Communion or its constituent national churches have always consulted Rome or Constantinople before making a decision that had ecumenical ramifications (such as the ordination of women to the episcopate).

Further, as my friends remind me, there are probably more Catholics – including priests – who have “swam the Tiber” in the other direction than Anglicans who have come into communion with Rome over the last three or four decades.

We also spent some time discussing the theology of the episcopate – or lack thereof – in the apostolic constitution, and wondered why at least a “conditional” ordination wasn’t proposed given the development of Catholic theology on orders in general and Anglican orders specifically since Leo XIII issued Apostolicae Curae.

I have an upcoming post updating my thoughts on the constitution, and I am incorporating some of my gleanings from this conversation there, so I do not want to duplicate it here!

Rome Reports

The local English-language news service just came in to film a special on the Lay Centre, and yours truly got to be the “stock footage of student working in his room”. Probably some great shots of my fingers typing, or the back of my head or something. The show is supposed to be out in a couple weeks; I will post a link when it does.

Translating Roman and American degrees

So, I am studying for a License in Sacred Theology (STL). What is that? How does it compare to the MA in Theology that almost/never was? How do the American and Roman degrees correlate?

Academic Biretta, worn by a Doctor of Sacred Theology

Rome has answered a frustration I had at CUA, which was shared by several of my classmates: the graduate courses there seemed to be really geared at a more basic, undergraduate level. Some blamed the overwhelming presence of seminarians, for whom classes had to be “dumbed down”. Others attributed it to “the lack of academic freedom” at the only U.S. University officially run by the Catholic Church (as opposed to a religious congregation or non-profit). I believe this to be primarily the result of the difference between the Roman and secular/American degree systems, and a less-than-efficient blending of the two.

Europe has a host of different practices, i find out, and for the last decade they have been in the process of synchronizing the systems. Some graduate secondary (high school) at 17, then have a 3-year bachelors program. Others graduate secondary at 19. Italy currently has what they are calling a 3+2 program for college studies, the three years for a bachelors, and the 2 for a masters – or what we might call a masters. But Italy is different than the Pontifical system.

In the pontifical system, you earn the Baccalaureate first, then a License, and then a Doctorate. If you are studying theology, however, you need at least two years of Philosophy first, then a Bachelors in theology, before doing the License and Doctorate. So, the STB really is an undergraduate degree, and it makes little sense to compare it to an M.Div., though these are respectively the basic ministry degrees required by each system.

So, if one were to go straight through in each of the systems it would look something like this:

| HS + yrs | Pontifical | American |

| +1 | ||

| +2 | Philosophy (no degree) | Associate (AA) |

| +3 | ||

| +4 | Bachelor (BA/BS) | |

| +5 | Baccalaureate (STB) | |

| +6 | Master (MA), or | |

| +7 | License (STL) | Professional (M.Div.) |

| +8 | ||

| +9 | Doctorate (STD) | Pastoral Doctorate (D.Min) |

| +10 | Research Doctorate (Ph.D.) |

Thus, my License is both the completion of the work i began at CUA for the MA in Theology, and the begining of my doctoral work.

The Rector Magnificus

It is said that the Dominicans have the best sense of humor, and this is because humor is a necessary part of Dominican spirituality. Without question the funniest guest we have had yet at the Lay Centre is the Rector Magnificus (read: President) of the Angelicum, Father Charles Morerod.

Charles Morerod, OP (Facebook photo)

After celebrating the Eucharist with us, the topic of Father Charles’ discussion was on what it means to be a Dominican. A Swiss Dominican serving as rector of the Angelcium, Secretary of the International Theological Commission, and one of three Catholic representatives on the ongoing dialogue with the schismatic sect of Marcel Lefebvre, there was plenty beyond the Order of Preachers to ask about. (as if that resume is not enough, Fr. Morerod is actually on Facebook! Yes, you can find him on my friend list!)

St Dominic was a Cathedral canon with the Bishop of Osma, Spain on a journey to make arrangements for a royal wedding which never happened. Passing through regions of France dominated by the Albigensians/Cathars, Dominic was taken by the lack of good preaching in the region, which lead the poorly catechized residents to gravitate toward the dualist heresies. Further, he was disturbed by the fact that many of the preachers that were available to the people of the region were failry weatlthy monastics or papal legates. So, instead of returning home, he stayed to preach and eventually a following grew.

St. Dominic, Founder of the Order of Preachers

He was an efficient organizer, and conscientious that the community not become “his” community (reminds me of Father Scott!) – In fact, his humility was so complete that when he died, his order buried him and promptly forgot which grave was his. When, 13 years later, Pope Gregory IX wanted to formally canonize Dominic, the Order was not entirely sure where to find him. Making their best guess, they opened a sarcophagus and discovered “the smell was quite pleasant, so, it must be the saint!”

Grand(father) Inquisitor at the Lay Centre

Dr. Donna Orsuto, Most Rev. Luis Ladaria Ferrer, SJ

When meeting with the second-ranking official of the dicastery known for most of its history as the Holy Office of the Inquisition (now the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, CDF), one might not expect a relaxed and cheerful pastor.

One certainly does not expect to hear such pearls as, “We are not here to judge who is ‘really’ Catholic and who is not. We are all striving for holiness, but none of us has reached it. We offer people formation in the Catholic ideal, but everyone struggles with the real application of this in their life” or “Let him who is without sin cast the first stone!”

Yet, this is exactly what we got in the “grandfatherly” Jesuit Spaniard, Archbishop Luis Ladaria Ferrer, Secretary of the CDF at Tuesday night’s inaugural Oasis in the City at the new location of the Lay Centre.

Oasis in the City event at the Lay Centre

Equally reassuring of the man’s Christian heart was his reaction to the fact that the car service that had been arranged to get him to the Lay Centre was 45 minutes late, having left the Archbishop waiting for his ride, without any notice. Any normal person could reasonably expect to be irritated or upset. A typical “VIP” might have just given up and given up on us. More than a couple U.S. hierarchs I have encountered might have thrown a royal fit at such inconvenience. But when the archbishop finally arrived, he got out of the car laughing and waving away Donna’s profuse apologies as if they were not even needed: “These things happen all the time”, he says.

Archbishop Ladaria, Secretary of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith

The bulk of his lecture was on the unsurprising CDF 2008 instruction Dignitas Personae, dealing with a range of bioethical issues including IVF, stem cells, and cloning. It was the questions afterword that brought some of the most interesting comments, including the two quotes above, the first being in response to a question about where to draw the line when someone (such as a politician) does not act or profess a view entirely commensurate with Catholic moral teaching on these complicated issues. Others challenged the Church’s insistence that “human life/personhood begins at conception” from a Thomistic framework which allows for a later development.

My Italian is not good enough to have followed the lecture in its entirety, but the conversation afterword was just as lively. Now if only all of our American hierarchy were as pastoral as this CDF honcho! (Yes, you read that correctly!!)

UPDATE: Didn’t realize the press was here too: http://www.catholic.org/international/international_story.php?id=34844&cb300=vocations