Snow

You may have noticed the light dusting of snow falling on the blog. It hardly feels like December without it, and i was sitting on the terrace this weekend in only a T-shirt soaking up the sun, so i do not anticipate seeing the real thing while in Rome. I thought it was nice of wordpress to offer a taste of winter for those of us in more tropical climes!

My courses…

Allora… people have asked, and I keep forgetting to answer. This is my fall semester lineup:

The Catholic Church in Ecumenical Dialogue

Rev. Dr. Frederick Bliss, SM, Professor incaricatus from New Zealand

Hebrew Bible, Human Rights, and Interreligious Dialogue

Rabbi Jack Bemporad, visiting professor from the Center for Interreligious Studies, USA

Knowing the Christian East: Encounter and Experience

Rev. Dr. Joseph Ellul, OP, professor incaricatus from Malta

Methodism and its Dialogue with the Catholic Church

Rev. Dr. Trevor Hoggard, Methodist Representative to the Holy See, from U.K.

Monsignor Donald Bolen, former staff of Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity, from U.K.

Philo of Alexandria and his Influence on Early Christianity

Dr. Adam Afterman, visiting professor from Hebrew University, Jerusalem

Prophecy and Wisdom

Rabbi Jack Bemporad, visiting professor from the Center for Interreligious Studies, USA

Reception and Receptive Ecumenism

Rev. Dr. Frederick Bliss, SM, Professor incaricatus from New Zealand

Russell Berrie Fellowship Seminar in Jerusalem (Feb 5-13)

Various lecturers, coordinator: Dr. Adam Afterman of Shalom Hartman Center and Hebrew University

Social Teaching in Pope John Paul II

Various Lecturers, coordinator: Sr. Dr. Helen Alford, OP, Dean of the faculty of Social Sciences, from U.K.

Sociologia della Conoscenza (Sociology of Knowledge, in Italian)

Dr. Bennie Callebaut, visiting professor from Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium

Hebrew Bible, Human Rights, and Interreligious Dialogue

The second Oasis in the City event hosted at the Lay Centre this year featured a presentation by Rabbi Jack Bemporad on the topic The Hebrew Bible, Human Rights, and Interreligious Dialogue. Among his 30 years of experience in international interreligious work, Rabbi Bemporad is the founder and director of the Center for Interreligious Understanding in Englewood, NJ, and has been a visiting professor of Interreligious Dialogue at the Pontifical Angelicum University for 13 years. He has been invited by the Holy See to speak on matters of Jewish-Catholic relations, and met on several occasions with Pope John Paul II personally.

During his comments to the Lay Centre residents and community guests, one of the points Rabbi Bemporad raised was the tremendous work of the Catholic Church through Vatican II and especially the efforts of Pope John Paul II with respect to the Jewish community and the relationship of the two religions. Despite the wealth of documents from the Church, he said, especially the USCCB document, God’s Mercy Endures Forever: Guidelines on the Presentation on Jews and Judaism in Catholic Preaching, the international Jewish community has yet to examine its own long-standing description of Christ and Christianity at the same level.

The Hebrew Bible is primarily an account of monotheism directed at those who are not yet monotheists. Further, the revelation of monotheism is integral and necessary for a truly peaceful vision of the world and for the development of the concept of human rights.

“One God implies the possibility of a world of peace and justice. As long as there exists the battle between the gods and the plurality of gods as embodying separate forces of nature, then there is no sense of a world at peace. One God implies one world and one universal goal of justice and peace embodying the greatest possible realization for each individual.”

Six key themes or aspects of the Biblical message highlight the origination of human rights in the Hebrew Bible:

Equality in the Bible does not refer primarily to those of the same rank or class, but indicates a positive action of bringing up those who are weaker than oneself (widow, orphan, stranger, the poor and the slave).

The holy and ethical are inseparable. The prophetic tradition, with Amos as the first clear example, claim that social injustice –not simply idolatry or non-orthodox worship – will bring about national ruination. The value and destiny of a nation is dependent on how it treats its most vulnerable members. This social concern for the vulnerable can be traced back to Israel’s enslavement in Egypt.

The Biblical condern for the stranger and sojourner is essential. Love your fellow human being – not “as yourself” as is often translated – but “because he is like you”. There is but one law for you and for the stranger – a concept still foreign to most nations today!

Sabbath as an institution, which allows even the slave and the stranger to rest and be master of their own time for at least one day a week. By extension, the sabbatical year and the Jubilee year remind us that we are not owners of the land or of property, but stewards only. Poverty and wealth alike are only temporary.

A king is subservient to the law, not the law unto himself. The messianic king will be unlike all other kings, rather than to make war, he will make peace.

Finally, two elements that separate Judaism from the black-and-white view of “our religion is the true one, and all others are totally false and therefore evil”: First, the establishment of the Noachide as a status that taught that one did not have to be an Israelite to be saved. Second, the Tosephta enunciated that “the righteous of all nations have a place in the world to come” an idea now nearly universally accepted in Judaism.

The questions of interreligious dialogue, and our common work in support of human rights, remain: “How can I be true to my faith without being false to yours?” and “What is the place of the other religions I our own self-understanding?”

In the States, according to Rabbi Bemporad, it was the civil rights movement that joined Jews and various Christians to working together, and so we must continue to dialogue to discover the “common moral and ethical elements that are constitutive of our religions and try to unite on a common ethic independent of our theological perspectives.”

Saint Andrew the Protoclete

Andrew was the first Apostle of Our Lord, first having been a disciple of John the Baptizer. Sometimes, for some reason, my fellow western Christians forget this and refer to Peter as the first. Peter would have died an anonymous Galilean fisherman if not for his brother, Andrew, who brought him to the Christ.

One of the early successors to Peter and Paul decided to settle the question of when the church year should begin by determining that the first Sunday of Advent, and therefore the first Sunday of the ecclesiastical year, should be that Sunday nearest the feast of the first Apostle. Before that, advent was celebrated in local churches as anywhere from three days to six weeks.

My patron and namesake is also patron of Greece, Russia, Scotland, and Romania, as well as the apostolic founder and patron of the Holy See of Constantinople and the Ecumenical Patriarchate.

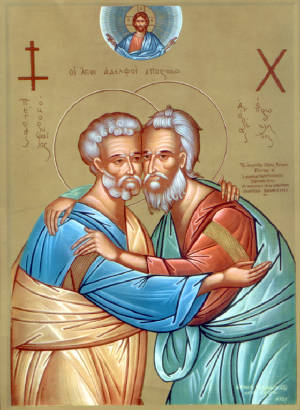

One of my favorite icons is of the brothers Andrew and Peter embracing. This Icon of the Holy Brother Apostles was written for the 1964 meeting of Patriarch Athenagoras I and Pope Paul VI, a gift from the Successor of Andrew to the Successor of Peter, as a sign of the fraternal relationship of the two churches (also called “sister churches”). A copy of this icon was given to me for my service on the National Planning Committee of the NWCU by then-chairman Allen Johnson.

While much of the western ecumenical world was caught up in the announcement by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith about the Anglican-Catholic personal Ordinariates in October, Cardinal Kasper joined Metropolitan Zizioulas and other representatives of the Catholic and Orthodox Churches on Cyprus for the 11th plenary round of the Joint International Commission for Theological Dialogue. The topic of this round of conversation is “The Role of the Bishop of Rome in the Communion of the Church in the First Millennium”.

In honor of the feast of Andrew, the Holy Father sends a personal message and a high-ranking delegation to the Patriarch of Constantinople; a return delegation is sent to the See of Rome to honor the patronal feast of Sts. Peter and Paul every June 29. This year’s address indicated signs of hope for the ongoing dialogue and the central questions to our restored unity – the role and relationship of the universal primacy of Rome and the other major Patriarchates, and the local churches.

The Holy Father’s message to Patriarch Bartholomew for the feast of St. Andrew today highlighted this work as a sign of the growing unity of the churches, and acknowledged the many areas for cooperation even as we are still on the journey to full unity.

Patriarch Bartholomew’s message of welcome to the Roman delegation likewise highlighted the work of the Commission, now tackling some of the most fundamental ecclesiological issues which remain to divide us, namely, primacy in general and that of Rome in particular.

“We are, therefore, convinced that the study of Church history during the first millennium, at least with regard to this matter, will also provide the touchstone for the further evaluation of later developments during the second millennium, which unfortunately led our Churches to greater estrangement and intensified our division.”

He also called attention to the slow progress being made toward the calling of a Great Council of the entire Orthodox world, an event which has not happened in centuries, and which would be akin to an Orthodox Vatican II.

Dinner, the Roman way.

We walked to the ristorante, got there at 10:15pm.

Red house wine, acqua (still), and pizzas, which arrived at almost 11:00.

Ordered dessert at 12:00 midnight. Some kind of delicious strawberries and creme with hot drizzled chocolate and cocoa.

Going to bed at 1:30am, listening to the discotech music coming from around the Colloseum (ah, to be young!).

Post-script: Fireworks at 1:50am, right outside my window. Literally, between here and il Colosseo.

Skeletons, saints, and scandalous ecstasy

An unexpectedly beautiful Saturday afternoon today in Rome. There was nothing to be done but go for an afternoon passagata around to some of the better-known churches in Rome.

Just across the street from Santa Susanna is Santa Maria della Vittoria, best known for Bernini’s sculpture of St. Teresa in Ecstasy, which he completed in 1652. The church itself is quintessential Baroque, overwhelming the senses. Built as a chapel for the Carmelites, it is currently the titular church of Cardinal Sean O’Malley of Boston.

We also wanted to go in for a more casual perusal of Santa Susanna, but it was closed for the day. Likewise, San Pietro in Vincoli (Saint Peter in Chains) which we stopped at on our way from the Lay Centre. It is easy to forget about that three hour lunch break sometimes.

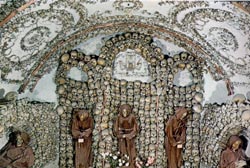

Not far from Susanna and Maria della Vittoria, on the pricey Via Veneto, is the church of Santa Maria della Concezione dei Cappuccini (St. Mary of the Conception of the Capuchins), the ossuary of which is generally known as the Capuchin Crypt. Famously macabre, the crypt is six rooms decorated almost entirely with the mortal remains of about 4000 Capuchin friars who died between the 16th and 19th century.

“What you are now we used to be; what we are now you will be…”

The Challenge of Priesthood

This should not be the topic of my first blog touching on the Year of the Priest. Maybe it should a story of vocation, or a theological reflection on the priesthood of Christ and his church. Perhaps an ecclesiological exposition of the ministerial priesthood of the bishop, presbyter, and deacon, with ecumenical emphasis. That is the price of procrastination, however. Those will come in time.

I came across both of these articles yesterday evening, and it was too powerful to avoid.

The first is from my diocesan newspaper, the Catholic Northwest Progress, in part of a series highlighting the presbyterate of the archdiocese in honor of the Year of the Priest; they provide brief profiles of five pastors each issue. This week’s issue includes five whom I know personally. Two were in seminary formation with me; two have worked with me as collaborators for the pastoral leadership of a parish; I have had several conversations with each, and have known most of them since I was 17 or 18.

Given that familiarity, I was mostly skimming the profiles. What priest does not think the greatest joy of being a priest is celebrating the sacraments, anyway? (Well, OK, there was one). I almost missed “the greatest challenge as a priest” on my first read, but that is the most telling part. Most of us who are or have been in pastoral ministry find that time-management and administration is an omnipresent challenge, and legitimately so. Yet, one response truly stands out, and calls us to remember what ministry, and the presbyterate, is really about.

To then turn to the next article only confirmed that read. Archbishop Diarmuid Martin of Dublin addressed this week’s release of the national investigation of the sexual abuse of children and its systematic cover-up by the Catholic hierarchy in Ireland. The report itself reads much like the reports in the States over the last ten years. What reads differently is the response of the archbishop himself, which should be read in full and is available here:

Three times, the archbishop repeats that “No words of apology will ever be sufficient.”

He acknowledges not only the profoundly sinful nature of the acts of abuse by priests, but also the abject failure of the bishops and religious superiors to act for good:

“One of the most heartbreaking aspects of the Report is that while Church leaders – Bishops and religious superiors – failed, almost every parent who came to the diocese to report abuse clearly understood the awfulness of what has involved. Almost exclusively their primary motivation was to try to ensure that what happened to their child, or in some case to themselves, did not happen to other children.”

He does not equivocate, blame the media, secular society or anti-Catholic bias; he does not claim that they ‘did not understand’ the nature of the pedophile and the ephebophile thirty years ago, or that they needed a ‘learning curve’ to adequetely deal with these problems. He makes no excuse for the culture of clericalism and institutionalism that allowed and encouraged the perpetuation of grave sin:

“Efforts made to “protect the Church” and to “avoid scandal” have had the ironic result of bringing this horrendous scandal on the Church today.”

In his interview he refers to the people making these excuses as a ‘caste’, a group who thought they could do anything and get away with it – which makes the crimes all the more horrendous because they were perpetuated by those who serve in the name of Jesus Christ.

There may be a long way to go before all remnants of that caste-mentality are eradicated from the Church, but our prayers and dedicated efforts to that end must never cease. Structures of sin have no place in the Body of Christ.

It reminds me of a parishioner whose daily intercession at Mass was for the “holiness of our priests” – simultaneously a prayer of gratitude for the many holy men who serve the Church, and a plea for the conversion of the rest.

Amen, indeed.

An American Thanksgiving in Rome

When I was studying in the states, at Notre Dame and Catholic University, Thanksgiving was a welcome calm before the storm, a few days to catch one’s breath before the final push toward final exams. Here, the semester is just nearing mid-term, and of course it is not an Italian holiday. I did notice that none of the NAC residents came to class today: The North American College, the residence for diocesan seminarians and priests from the states, had their big Thanksgiving feast for lunch.

Our director, Professora Donna Orsuto and our chef, Feda, spent all day preparing a traditional Thanksgiving feast for the residents and about 25 guests. We had invited classmates and other ‘homeless’ Americans to join us. Two gorgeous roast turkeys, mashed potatoes and gravy, corn and green beans, stuffing, and even pumpkin pie. I was appropriately stuffed. We’re pretty well fed, and Feda does a great job with the Italian fare every night, but for the visitors who were used to living on their own in Rome I think getting a taste of home was truly appreciated.

It is always a nice surprise when a member of the community shares a gift that you did not know they had. The other American students in the house are a married couple, Greg and Karina, from Chicago and Houston, respectively. Karina closed our feast with a soulful rendition of Amazing Grace in a beautiful voice. You could hear a pin drop. There is much to be thankful for, being in Rome in such a community, but moments like that highlight the gifts God gives in a special way.

Happy Thanksgiving from across the pond! May you be blessed with bounty, faith, and friendship!

Flocks of Anglicans

It has been almost a month since the CDF press announcement of the apostolic constitution, Anglicanorum Coetibus, which was released a couple weeks later. As with all Vatican documents, the title comes from the first two words in the official Latin edition, in this case, “groups of Anglicans” – though I prefer the translation “flocks of Anglicans”, probably inspired by the starlings and their Tiber-crossing aerial acrobatics, or the wishful thinking of certain (Catholic and secular) media outlets.

Along with the constitution itself, a set of complimentary norms and an official explanatory note was issued. The later is written by the rector of the Pontifical Gregorian University here in Rome, Gianfranco Ghirlanda, SJ, a native Roman who is trained as a civil and canon lawyer – which is an important lens to keep in mind when reading his commentary.

In the last three weeks, I have heard this issue addressed, in person, by Archbishop Rowan Williams, Cardinal Walter Kasper and about a dozen other curial officials, Catholic ecumenists, and Anglicans. My comments and conclusions remain my own, so do not blame any of them for my errors, but each conversation has provided some insight to various aspects of this issue, for which I am grateful.

Communication and timing

Much has been said of the Holy See’s lack of a modern communications strategy this last year, starting especially with the lifting of the excommunications of the (still) schismatic bishops of the Society of St. Pius X. In this case, the timing issue has been remarked on a great deal.

But let us be realistic: This is the Vatican. In Rome. Do you have any idea how long it takes to get anything done here? How many good people in the Church have been frustrated by an organization that prides itself in “thinking in centuries”? Should we really believe that this was an ambitious gambit at Ecclesial Imperialism incited only by recent developments? A rushed effort to ‘fish in the Anglican pond’?

I honestly think the more likely answer is that this is, at least partially, the long, slow, overdue response to requests that came way back in 1997 from some groups that left communion with the Anglicans at that time, just as the 1980 Pastoral Provision was a response to a smaller-scale situation in the 70’s. These former Anglicans are likely the ‘target demographic’ rather than current members of the Anglican Communion. I would not be surprised if some draft of something like this had been floating around in a dusty file cabinet in the CDF for the last decade or more.

It is probably, genuinely intended as a pastoral response by some in the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, and possibly the Secretariat of State. However, these impulses have not benefited from the full reception of, or formation in, ecumenical dialogues and relationships.

The internal, inter-dicasteral communications and collaboration is also clearly a problem, and it has not improved much in the eight years since Dominus Iesus. The Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity was not properly consulted in the development of the document, only verbally informed of it after it was in process. Cardinal Kasper did say on Thursday after the Colloquium that he had seen a draft of the Apostolic Constitution before the official promulgation, and was invited to make recommended changes, but he did not mention the accompanying documents, and this may have happened after the initial press conference with Cardinal Levada and Archbishop DiNoia.

Externally and ecumenically, the Archbishop of Canterbury and his staff, as well as even the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales was likewise not consulted or involved in the process, but only informed shortly before the press conference. Seemingly it was informing them that motivated the conference, for fear of leaks before the Constitution was finalized.

Anglican Responses

The official responses are out there to read on the internet. Bishop Chris Epting, National Ecumenical Officer of the Episcopal Church, has recently blogged about the issue; and the press has been following Archbishop Rowan Williams everywhere in Rome, so there is no shortage of coverage.

Personal responses among those I have spoken with have included some common themes, including brief temptation and excited interest: “Enough talk, let’s just do it! We can have unity now!”

This was usually followed by disappointment in some key aspects once the constitution, complimentary norms and explanatory note came out. After a little time, there has been a sense of betrayal of the ecumenical bonds of unity that already exist and anger at what seems to be promotion of an “ecumenism of return”, which the Catholic Church disavowed 50 years ago. One local Anglican’s comment of “not being angry about this… but then being surprised at how angry I was” is echoed in several remarks, also among dedicated Catholics sensitive to the challenges currently facing the Anglican Communion.

Personally, I was initially excited too, “What if they all came? What if we could just have unity now?”… for a few minutes. Then a mea culpa for my momentary indulgence in ecclesiastical imperialism, and my thoughts turned to friends yearning for full communion, and the personal discernment of one friend in particular between coming into communion personally or continuing the long slow work of full ecclesial union.

Chris, Nigel, Andrea, John, Stian, Ann, Chris, Liz, Terry, Peter, and Tom: You are regularly in my prayers, you know, but have been especially so in recent weeks. Nothing would make me happier than being able to break bread together, in the fullest sense, but I suppose we can wait a little longer! (In the short term, I should at least practice better communicatio in communication and start answering email…)

Personal Ordinariates: Neither Personal Prelature, Church sui iuris, nor pastoral provision

The Personal Ordinariate structure was not foreseen in the 1983 Code of Canon Law, so Pope John Paul II created it specifically for the military ordinariates in 1986. The point missed in most of the media is that this is specifically a structure for the People of God – unlike a Personal Prelature (eg, Opus Dei) or the pastoral provision, which are specifically about clergy. The personal ordinariate is a personal diocese, not just a provision to “get married priests” in through the back door and “fill the dwindling ranks”. Were that primarily the motive, I think we would have just had a personal prelature.

Neither is it a full, autonomous Church sui iuris (or Particular Ritual Church) like the 23 Churches that make up the one Catholic Church. (That is, the Roman Catholic Church, Maronite Catholic Church, Ukranian Greek Catholic Church, etc.) This is a model proposed at various times in the ecumenical conversation as a juridical/ecclesial structure for eventual full communion, with the Archbishop of Canterbury as the Patriarch (or Major Archbishop).

Fr. Ghirlanda’s commentary acknowledges that the creation of such a structure could create “ecumenical difficulties”, without elaboration. Not knowing which difficulties he was thinking of, two immediately come to mind: 1) the idea that such a structure should be reserved until such time as we do attain full communion between Rome and Canterbury, and to do so now would be really insulting to the Anglican Communion and its leadership, and 2) a concern for our relations with the Eastern and Oriental Orthodox, who might object to the unilateral establishment of a new patriarchate by Rome that did not exist as such during the first millennium.

However, the reason given in the commentary is that “the Anglican liturgical, spiritual and pastoral tradition is a particular reality within the Latin Church.” This has been one of the moments of pause for some Anglicans and former Anglicans who might otherwise consider the move.

I think this can be read positively, as acknowledging a genuine tradition that goes beyond local custom and has a proper place in the Catholic Church today at a level similarly given to, say, the “extraordinary form” of the Roman Rite, rather than seeing it as a ‘non-Catholic creation of the English Reformation’. However, it seems safe to say that the English church has long recognized in itself an ecclesial tradition distinct from the Roman church, even for the many centuries of full communion, which goes beyond just liturgy and spirituality to a full ecclesial sense, including juridical, pastoral, and theological practices. This limited recognition is not as generous as would have been hoped.

Theology of Bishops, ordination

When is a bishop not a bishop? Would a rose by any other name still smell as sweet? If it walks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck, isn’t it a duck?

[First, a brief note: “Ordinary” is a canonical term used to designate a person whose authority is by virtue of law itself in relation to his office. We refer to the diocesan bishop as the ordinary, in distinction from any auxiliary or retired bishops in the diocese. So, in itself, the “ordinary” is not a new term or office.]

One of the first discordant notes from the press announcement three weeks ago was around the identity and role of bishops and the ordinary in the personal ordinariates. Anglicanorum Coetibus basically sets up the ordinariate and outlines the responsibilities of the ordinary and the consultative structures. It gets interesting in the complementary norms (particular law).

First, in article four of the norms, it is noted that the ordinary may be a bishop or a presbyter. While allowing a presbyter exercise ordinary power is not unusual in itself, it is odd for the role equivalent to a diocesan bishop. In fact, the canons specifically mentioned in this article are describing the roles and responsibility of a diocesan bishop.

The section on “Former Anglican Bishops” (Article 11) has four points:

- A former Anglican bishop may be appointed as the ordinary, but he would be only ordained as a presbyter.

- A former Anglican bishop who is not ordinary could be asked to assist the ordinary in administration of the ordinariate.

- Any former Anglican bishop would be a part of the bishop’s conference in their territory (such as the USCCB), with a status equivalent to retired bishop.

- Finally, any former Anglican bishop who is not ordained as a Catholic bishop may request permission to continue using episcopal insignia (mitre, crozier, pectoral cross, ring, and presumably the amaranth red zucchetto, fascia, and simar).

While the first point seems to say that a former Anglican bishop could not be ordained as a bishop, even if he is the ordinary, the last point seems to indicate that at least some former Anglican bishops could be so ordained, and the rest could continue to wear bishop’s regalia even if they are not ordained as bishops.

Turning to Fr. Ghirlanda’s commentary for clarification, one finds the following:

“The ordination of ministers coming from Anglicanism will be absolute, on the basis of the Bull Apostolicae curae of Leo XIII of September 13, 1896. Given the entire Catholic Latin tradition and the tradition of the Oriental Catholic Churches, including the Orthodox tradition, the admission of married men to the episcopate is absolutely excluded”

This is where any interest in ‘coming over’ grinds to a halt for many Anglo-catholics, especially the clergy. Among Catholic ecclesiologists, ecumenists, church historians and sacramental theologians, this is probably where there was a collective raising of eyebrows. The three issues here are the use of Episcopal insignia by non-bishops, the nature of Anglican orders and of ordination in the personal ordinariate, and the whole of the final sentence regarding ordination of married men to the episcopate.

Episcopal Insignia

Originally, of course, bishops did not wear anything different than the rest of the people of God. After Christianity became the official religion of the empire, Emperors began appointing Christian bishops to civil magistrate posts. These secular offices included the insignia of a ring and what have become the crozier and mitre. As the empire dissolved and the Church took on the role of the state more completely, they became identifiable with the episcopal office, but continued to have a secular connection.

The whole (unfortunately named) lay investiture controversy of the 12th century had nothing to do with the role of the laity in electing their bishops (which was traditional), but with the role of the secular rulers appointing bishops themselves and/or retaining the right to invest them with the ‘secular’ signs of office: ring, mitre, and crozier.

Significant to that argument and church practice since is that these are insignia of the episcopal office, and are neither appropriate for non-bishops to use nor for non-ecclesiastical authorities to confer. The exception to this concerns some of those who are equivalent to a bishop in office, such as an abbot (and in some places in the past, an abbess). Given that exception, it would be consistent to allow the ordinary of the personal ordinariate to retain episcopal insignia even if he was only a presbyter.

The underlying concern is twofold, one ecumenical and the other ecclesiological. First, having just reiterated the judgment of Apostolicae Curae of Anglican orders as “absolutely null and utterly void” and declaring that any former Anglican bishop, presbyter or deacon would have to be absolutely ordained, the allowance for former Anglican bishops to adopt episcopal insignia without episcopal ordination basically says, “Because you are used to pretending to be bishops, we will allow you to continue pretending to be bishops, even though you will not actually be bishops.”

Secondly, the practice of having non-bishops dress or act as bishops seems to imply the Tridentine theology of the episcopate as a merely juridical office, rather than as an order in itself. If a presbyter has the fullness of orders, and being bishop is just a “job”, then a presbyter can dress as a bishop or fulfill a bishop’s office (eg, ordinary) without actually being a bishop. Catholic ecclesiologists and sacramental theologians are not too happy about that possibility.

Apostolicae Curae and Anglican Orders

Many catholic-leaning Anglicans are that way because of a Catholic understanding of the sacraments, including holy orders and the Eucharist. They may have been interested in the personal ordinariate if offered a “conditional” ordination, which would at least acknowledge the possibility of, or partiality of, sacramental validity of their current ordained ministry. But absolute ordination means a betrayal of their (very Catholic) sacramental sense of their current ministry, which is not appealing.

In the 113 years since Apostolicae Curae, Catholic historians, theologians, and ecumenists have developed a more nuanced understanding of Anglican orders. The bull is considered definitive church teaching on precisely the issue with which it deals – Anglican ordinations conducted according to the Edwardian Ordinal from 1552 until 1662.

Church historians have discovered at least some places where this ordinal was not used, and so would not be subject to the declaration of nullity. More recently, there have been more and more Anglican ordinations including bishops of the Old Catholic churches, which are generally recognized as valid in the classic Catholic understanding, and the Scandinavian Lutheran churches, which also maintain an historic episcopate with a claim of apostolicity. Even the Catholic understanding of ordination vis a vis Apostolic Succession and Tradition has enjoyed development, at least in ecclesiological circles, in moving from a “spiritual heredity” model to a more collegial understanding of succession and ordination as incorporation into the episcopal college.

Given all of these, it was disappointing for many that the ordinations of former Anglican clergy were not classified as conditional. This could be understood either as “just in case” their former ordinations were either absolutely invalid or merely defective, or, even better, as a sign of their incorporation into the episcopate, presbyterate, or diaconate in communion with the ordinary and the bishop of Rome, without judgment on the state of their current orders or past ministry.

Married Bishops

Finally, there is the sentence about married bishops. The best way to read this is to recall that Fr. Ghirlanda is primarily a canonist, and is a native Roman.

In the current canonical situation, it is true that married men are absolutely excluded from the episcopate in the entirety of the Catholic Latin and Eastern traditions, as well as in the Eastern Orthodox tradition.

Historically, of course, married men have been bishops (and before that, apostles). This was common in the Latin tradition, and not unheard of in the east, until celibacy became a universal norm in the Latin Church during the 12th-16th centuries. Early on, the practice of selecting monastic (and therefore celibate) presbyters to be bishop became the norm in the East, while the West continued to select bishops from the diocesan (and therefore married or celibate) diaconate and presbyterate. Ecumenically, the Orthodox Church recognizes this historic difference in praxis, and does not generally object to married bishops in the Latin Church. Theologically, there is no impediment to a married man being a bishop in either the Catholic or Orthodox traditions, and in fact scripture commends it – though, admittedly, limiting bishops to only one wife.

Being a Roman, Fr. Ghirlanda has no doubt been to the Basilica of Santa Praessade, and has seen the 9th century mosaic of Episcopa Theodora. If he had meant that in the entire Latin Catholic tradition, historically and theologically, the admission of married men to the episcopate was absolutely excluded, then he would be confirming the interpretation that Theodora was not the wife of a bishop, but was in fact a bishop herself. This seems unlikely.

The Synodal Tradition of Anglicanism

As “the Anglican liturgical, spiritual and pastoral tradition is a particular reality within the Latin Church” according to the official commentary, their pastoral tradition of synodality (collegiality and collaboration) is also worthy of emulation in the entire Latin church, and perhaps some of the norms in this section will be applied throughout the church. Even if not, they are interesting in themselves.

A “governing council” combines the basically redundant structures of presbyteral council and college of consultors currently mandated in the Code of Canon Law. It is given deliberative voting powers on a number of issues, and interestingly, prepares the terna (list of three names) from which the Holy Father would appoint the ordinary. For most Latin dioceses, this terna is currently prepared by the Apostolic Nuncio, with consultation of the region’s bishops, some other clergy, and virtually no input by laity.

Further, the pastoral and finance councils are mandated not just for the ordinariate, as is the case for all dioceses, but also for all parishes in the ordinariate. For most Latin dioceses, the parish pastoral council is merely recommended. However, the language for pastoral councils in the norms is that they are “advisory” rather than the stronger “consultative” which is in the Code, though this is a common misreading of consultation, so perhaps it was not meant as a change.

What Happens Now?

Some former Anglicans may accept the offer, but I do not think it will be a large number. Even fewer current Anglicans will, I think. The most interested will thankfully continue to work on full ecumenical unity, distant as that always seems. I am interested to see how this develops, or if it develops.

One curial official described the personal ordinariates thus: The Holy See has set aside an empty room, but without furniture, electricity, or provisions. Now we are asking Anglicans to fill the room, without being able to bring anything with them other than themselves. It may remain empty for a long time.

In the mean time, the Anglican Roman Catholic International Commission (ARCIC) III preparatory commission is meeting in Rome this week, including my own bishop, Archbishop Alex Brunett as co-chair. This, after a hiatus since 2005, prompted by the developments in the Anglican Communion – a hiatus which some predicted would never end. If Anglicanorum Coetibus were really the Holy See’s ecumenical answer the Canterbury’s internal struggles, ARCIC III would be dead in the water. Yet, they seem energized and ready to go, so it will be interesting to see whether ecumenical dialogue or corporate conversion takes center stage over the next few months.

The Apostolic Constitution, Complementary Norms, and commentary can be read together here.